Chris Beale doesn’t call himself a photographer. Or a journalist. Or an activist. When asked his profession, the 42-year-old is quiet for a moment before replying, “Gardener. I’m a landscape gardener.”

But Beale, who is plainspoken and reserved, is also one of the first photographers to document the persecution of Rohingya in Myanmar that has led to an exodus of hundreds of thousands of refugees.

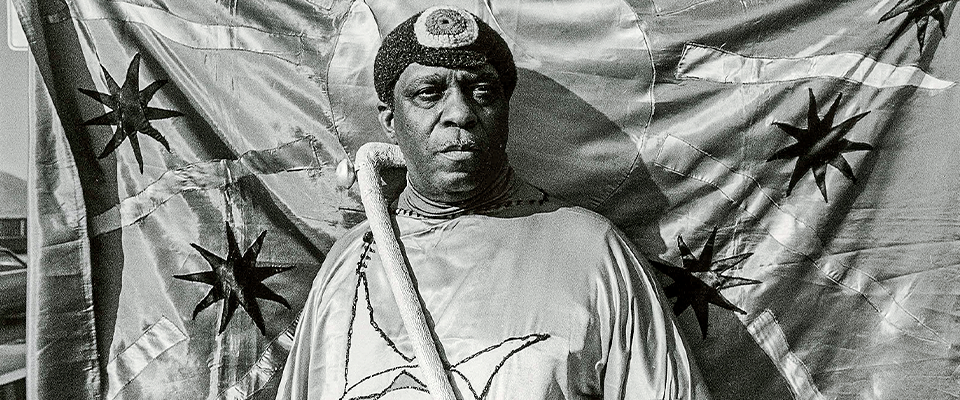

The resulting work is a collection of black and white film portraits that gives faces to the victims of the genocide. Beale’s photos are currently on display in Berkeley’s Human Rights Center (HRC) in Boalt Hall. It is the first public exhibit of the collection.

Beale first traveled to Myanmar in 2011, on a solo trip. He spent most of his time in the western province of Rakhine, which, like the rest of Myanmar, is primarily Buddhist. However, Rakhine is also home to a predominantly Muslim ethnic minority known as the Rohingya, who have lived in the coastal region for generations. At the time of Beale’s first visit, it seemed to him that the Buddhist and Muslim communities were naturally intertwined.

“I saw them doing business together,” Beale remembers. “I saw them every morning at the market together, I saw hundreds of Rohingya fishermen bringing fish into the market and selling them to the Rakhine people. I rode boats across rivers with mixed passengers of Rakhine and Rohingya. At that time, people were still living together like they had for centuries.”

But when Beale asked about the Rohingya, his guide—a Rakhine lawyer and human rights activist who agreed to show him around—made a firm point of denying the validity of the term itself, insisting instead that the people were Bengalis. His sentiment echoed government propaganda that, since the 1970s, has portrayed the Rohingya as illegal immigrants from neighboring Bangladesh. “It just didn’t seem right to me, something about the way he was saying it,” Beale recalls.

Six months after Beale left Myanmar, in June of 2012, a wave of coordinated violence broke out against the Rohingya. Rakhine extremists made the rounds of Rohingya villages, setting them on fire and forcing the people into camps. The entire Rohingya population in Rakhine State was actively sequestered while the police stood by and watched. “In certain cases, [the police] were making a border around the village while these extremist folks came in and did the dirty work.”

The news of the violence prompted Beale to return with his camera the following year—and every year since—to document the human rights crisis.

Multiple trips over several years were crucial to establish the trust of the Rohingya, whom he presents in his portraiture as individuals with unique stories. “There are too many pictures of just Rohingyas with their hands out getting food thrown at them or, you know, the big line of people crossing the border.”

Beale says that nearly everyone he met, with few exceptions, wanted to be photographed. The Rohingya—thousands of whom are now trapped in a ‘no-man’s land’ between Myanmar and Bangladesh, with many more living in refugee camps—are essentially a “forgotten people” who want the world to know the truth of what’s been going on. To some extent, this is why Beale feels it’s his responsibility to share the pictures.

Still, he knows that people who share their stories with him could be putting their lives at risk.

“I get to go home,” Beale says, “but they still have to live there and deal with what happens.” Since his first trip, it has become increasingly difficult to get into Myanmar, and the displacement camps are legally off limits.

Despite the increasing intensity of the crisis, Beale says it “took many massacres and many hundreds of thousands [of Rohingya people] coming across the [Bangladeshi] border” before anyone was interested in displaying his photos.

The scales were tipped at a Berkeley fish market, where Beale’s close friend worked behind the counter. The friend would occasionally chat about Beale’s project to regular customer Eric Stover, who is the director of the HRC. Stover eventually got in contact with Beale, and the two arranged to put his photos on exhibit at the center.

A hallway on the second floor of the Berkeley Law building, the walls of which previously featured portraits of past judges, now displays Beale’s work. The exhibit, titled ‘Rohingya: On the Edge of Existence,’ debuted with an event in October. At the unveiling, Beale spoke of the subjects in his photos, referring to each by name and sharing their stories.

The exhibit and event were co-curated Alexey Berlind, Programs and Events Administrator at the HRC.

A week after the opening, the exhibit made news when four of the photos were stolen. Although the circumstances surrounding their disappearance remain a mystery, Berlind was willing to hazard a couple of guesses: Maybe someone wanted it for their wall, or maybe it was politically motivated. “There are Burmese Buddhists here who might think this is fake news.”

Says Beale: “What I don’t understand is why someone would want to steal a portrait of a woman who watched seven of her children killed in front of her and her husband killed in front of her and got chopped in the neck and the chin with a machete. I’m not sure what turns someone on about that photo enough to wanna steal it, you know what I mean?”