Seated in her office behind a door bearing signs reading, “Warning: I have flying monkeys and I’m not afraid to use them!” and “What happens over the rainbow stays over the rainbow,” C.J. Hirschfield, the executive director of children’s Fairyland in Oakland, smiled as the sounds of toddlers gleefully sliding down one of the park’s newest attractions, the Jack and Jill Hill, a gently sloped mound covered with AstroTurf, filtered through her window.

“There hasn’t been a moment since it opened that it hasn’t been in constant use,” says Hirschfield, who admits the idea didn’t start with her. “I saw something like it when I took my daughter to the Santa Barbara Zoo. I took one look and thought, ‘Oh boy! It’s simple and low-tech and interactive! It would be perfect for Fairyland! Navlet and Mott would have loved it!'”

That’s Arthur E. Navlet and William Penn Mott, Jr., two Cal grads, Navlet in 1917, Mott in 1933. They envisioned Fairyland in 1948 and made it a reality two years later. Navlet, the owner of the largest floral nursery in Oakland, had just sold the business and retired, and he and his wife Alma celebrated by taking a cross-country trip.

When they reached Detroit, they saw a new children’s zoo that had just opened at the Belle Isle Aquarium. Instead of the usual concrete and iron cages, Belle Isle exhibited its animals in fanciful, fairy tale-like settings that showed off both the animals and the landscaping.

The Navlets were childless, but they had a deep and abiding love for kids, and their first thought was “Wouldn’t the children of Oakland love to have something like this in their own backyard?”

As soon as they got home, Navlet took his idea to the Lake Merritt Breakfast Club, the city’s premier service organization, and they agreed to sponsor a new children’s park on a 10-acre site on the shores of Lake Merritt. But Navlet still needed someone with the know-how to supervise the project.

He found his man in William Penn Mott, the Superintendent of Parks for the City of Oakland, who later became general manager of the East Bay Regional Park

District, Director of the California Department of Parks and Recreation under Gov. Ronald Reagan, and finally, when Reagan moved into the White House, Director of the National Park Service.

The two men’s age difference was bridged by their shared vision, and they hit it off immediately. Their first task was to hire painter, sculptor, photographer and industrial designer William Russell Everett to design the park. In two weeks, he presented them with a scale model of the first set, the Merry Miller’s Cottage, a perfect reproduction of a medieval English cottage, and he was delighted with the result. But Mott was not. He didn’t want realism, he wanted whimsy; a cockeyed, child’s-eye view of the grownup world.

Enraged, Everett grabbed a baseball bat and smashed the model to little pieces. Then he stormed out of the room, and Mott and Navlet were sure they’d never hear from him again.

But a week later he returned with a new model. It was oddly askew with no square sides, and it was painted in crazy colors.

“That’s it!” exclaimed Mott. And so was born the motto that has ruled Children’s Fairyland ever since: “No straight lines and a surprise around every corner.”

Everett went on to design many of the whimsical sets still in use at Fairyland; and, like Mott, he also had a notable post-Fairyland career: he was the nation’s top designer of miniature golf courses, whose wacky, lopsided structures clearly owe their look to the ideas he first came up with at Fairyland.

Meanwhile, Mott was spending a lot of time in the children’s room of the Oakland Public Library to see what the kids were reading that he could turn into sets for Fairyland. Years later at a party, he met the library’s director, Peter Conmey, who told him, “We used to see you hanging around the children’s section all the time, so we decided to put special guards on you to see just exactly you were up to. The staff thought you might be a child molester.”

Mott was amused by the suspicion, but the issue of child abuse was no laughing matter. So he and Navlet devised a simple policy to keep the creeps out of the park that has remained in force to this day: No child admitted without an adult, and—here’s the important part—no adult admitted without a child.

Soon the Merry Miller’s Cottage was joined by the Jolly Trolly, Willie the Whale (With the Curly Tail), the Happy Dragon, the Wonder-Go-Round, the Three Men in A Tub, and Oswald the Bubble Elf, who sits atop his giant mushroom blowing bubbles through his pipe. On the base of his mushroom is a plaque with a quote from Oscar Wilde: “The best way to make children good is to make them happy.”

On September 2, 1950, Children’s Fairyland opened to the public. More than half a million people visited the park the first year, entering through the archway in the Giant Shoe (as in the old woman who lives in a shoe), which is just big enough for a child to walk through upright, but grownups have to duck.

“It sends a subliminal message,” says Hirschfield. “It’s not all about them anymore.”

Within five years, dozens of “sister parks,” using the Fairyland model, sprang up in cities and towns across America, although only a handful still survive. But the most successful Fairyland spinoff was created by Walt Disney, a frequent visitor to the park before he built Disneyland, who not only used Fairyland as his model for Fantasyland, but also hired Fairyland’s director, Dorothy Manes, to be Disneyland’s Special Events Administrator, and its first puppeteer, Bob Mills, to run the marionette shows in Disneyland’s Tinker Bell Toy Shop.

“We don’t mind being ripped off because the more the merrier,” says Hirschfield.

And there’s one big difference between Fairyland and its imitators: From the start, Fairyland was designed to be interactive, not passive. Except for the Jolly Trolly and the Flecto Children’s Carousel, there are no rides per se. Children clamber all over the Pirate Ship’s rigging; pet the sheep, goats, ponies and miniature donkeys in the Animal Corral; climb down Willie The Whale’s gullet to see the fish in the aquarium in his tummy; play chimes, gongs, and harps on the walls as they run through the 118-foot Fairy Music Farm tunnel; eat munchies in the Teddy Bear Picnic Area; and take in a puppet show in the Storybook Puppet Theater or a live musical production on the Emerald City Stage or Aesop’s Playhouse.

And, yes, everything at Fairyland has a storybook name, including the Fountain of Youth drinking fountain and the Hansel and Gretel restrooms.

Navlet died on August 1, 1981. Mott lived another 11 years and returned to the park many times to visit his handiwork. His final visit was on September 21, 1992.

Randal Metz, Fairyland’s current master puppeteer, was one of the last people to see him alive.

“It was early in the morning, and he and I were the only two people in the park. There was something about the way he was looking at everything, and I asked him, ‘Are you OK?’ He said he was, then he went home and had his fatal heart attack.”

Metz is the fifth master puppeteer in Fairyland’s history, after Bob Mills, Tony Urbano, Luman Choad, and Metz’s friend and mentor, Lewis Mahlmann, the longest serving master puppeteer in Fairyland’s history, who served from 1967 until he handed the reins to Metz in 2003.

Many professional puppeteers got their start as apprentices at Fairyland, including a youngster named Frank Oznowicz, who later shortened his name to Frank Oz

and became the voice of Fozzie Bear and Yoda; and Alice Dinnean, who is currently in her 23rd year with the Jim Henson Company, working on the Muppets.

“The little theater at Fairyland was the inspiration for everything I’m doing now,” she says. “Lewis was a wonderful mentor. He was the one who told me that a puppeteer has to be all things—an actor, an artist, a playwright, a musician, a carpenter, an inventor, and impresario. I was very fortunate to have crossed paths with him.”

Dinnean started coming to Fairyland long before she became an apprentice puppeteer, first as a tiny visitor and then, when she reached the age of eight, as a storybook personality in Fairyland’s Children’s Theater Program (she was Winnie the Pooh).

The storybook personalities were the brainchild of another Cal grad, Burton Weber, who was special events coordinator for the City of Oakland. Although Fairyland was made for small children, some kids didn’t like giving it up when they got older. So he created the program to give them a way to retain their contact with the park.

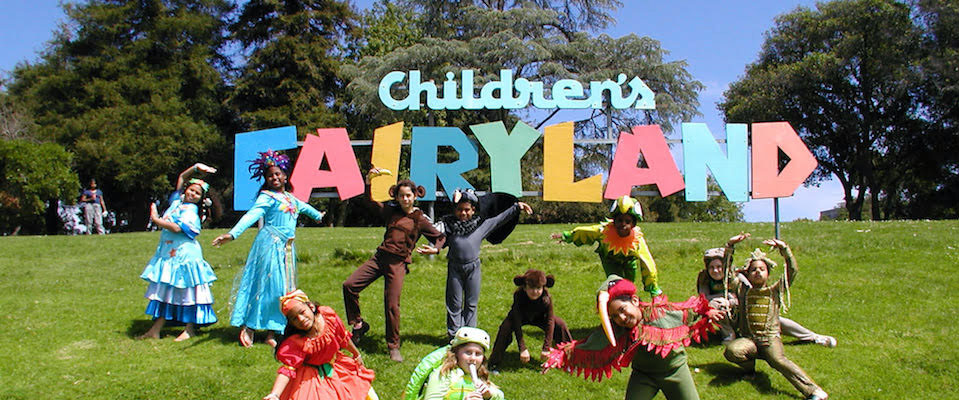

Every year, 30 kids between the ages of eight and 10 are chosen for Fairyland’s Children’s Theater Program, performing three different musical productions,one Anglo-European fairy tale plus two other shows from other cultures represented in Oakland.

“My personal vision for this theater is to have it run as much by the kids for the kids as possible,” says Director Doyle Ott. “I try to make sure I use their input in creating the shows.” They help create the show, and older kids run sound and stage manage, he says. “I help them warm up, and when the show starts I have the traditional director’s role of not really doing much.”

Another notable Storybook Personality Program alumna is Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf, who was Raggedy Ann in 1975. “It taught me how to speak in front of large groups, to be on time, to work well with others, and to be responsible for the commitments I make,” says the mayor, who still has her Raggedy Ann wig. “But most of all, it taught me to be kind.”

The storybook personalities also stay in character to greet visitors to the park, and represent the park at public events including the Jack London Square Christmas Tree lighting, the Chinatown Festival, the Walnut Creek Walnut Festival, and Oakland’s July 4th Parade.

“They always warned us to watch our step when we walked behind the horses,” recalls former storybook personality Katie Love.

But the role they seem to enjoy most is mentors and role models for the younger children who visit the park. They paint faces, read stories, and assist with arts and crafts. The tiny visitors repay this kindness with an adoration that verges on hero worship.

“The little kids look up to them so much,” says former Children’s Theater Director Karen Block. “It makes them feel special. You have to remember that to a five-year-old, a nine-year-old is a big kid.”

“We just treated them the same way Karen treated us,” says former storybook personality Alli Love.

In addition to its sets and attractions, Fairyland is also home to 17 kid-friendly animals: Pixie and Brownie, the miniature goats; Gideon and Chiquita Bonita, the miniature donkeys; Hippity and Hoppity, the bunnies; Pixie and Scamp, the ponies; Oatmeal and Raisin, the miniature sheep; Valentine and Mr. Luckii, the ducks; Lucy, Violet and Woodstock, the chickens; and Rosie and Patches, the guinea pigs. All of them are allowed to wander at will throughout the park whenever Fairyland is closed. All of them were named by the children, and, if history is any guide, all of them will live far beyond their normal life expectancies because of the loving care they receive.

“Chiquita and Gideon are a little bit mean to the goats,” says Animal Caretaker Maura McMichael. “They chase them off as soon as they come into the Merry Meadow, so the goats hang out with the sheep, instead.”

Cookie and Brownie, the goats, she says “are the smartest animals here by far. I let them follow me throughout the park.”

The bunnies, she says, like to snuggle but Hippity is also a jumper who could get out of the park if she wanted to, “But she doesn’t want to.”

The chickens, she adds are chatty but spoiled. “They won’t go to bed at night without a treat.”

And the guinea pigs? “Their favorite thing is to just hide. They’re introverts.”

A big part of what makes Fairyland so unique is the imaginative landscaping.

“After 60 years a garden can accumulate a wide variety of plant life,” says Landscape Supervisor Jackie Salas. “Things get cluttered. It doesn’t just happen in your house, it happens in a garden, too.”

“So when I came here I decided to start editing. I wanted to go back to what Arthur Navlet would have imagined himself,” she says. So she went back to his guiding principle of “a surprise around every corner.”

“For example, the Crooked Man had already been planted with a crooked camellia and a crooked hazelnut, so I added some curly willow. It was supposed to be a living fence, but the squirrels weren’t having any of that, so they ripped it out. I’m working with what I have, trimming the holly leaves and osmanthus into a crooked shape, and I added crooked corokia that the squirrels have no interest in.”

Not that she resents the squirrels’ meddling. “One of the things Navlet said was that he wanted animals and the gardens to exist in harmony. I take pride in sharing our space with the urban wildlife, as he envisioned.”

The Fairyland gardens have some new residents, too. Fairyland is a member of the Pollinator Posse, Oaklanders interested in raising butterflies and bees, protecting their habitats, establishing pollination corridors for them, and educating others about their importance. Currently, Fairyland is a safe haven for hundreds of carpenter bees, monarch butterflies, and fritillary butterflies, with the numbers growing each year.

“We have milkweed for the monarchs and passion flower for the fritillaries, and the bees love anything from the aster family, like daisies, black-eyed susans, and calandrinia, a little succulent plant with hot pink flowers,” says Salas.

The plant life isn’t the only thing that needs constant maintenance. So do the sets.

“‘No straight lines and a surprise around every corner’ is a brilliant idea, but it makes my job harder because on top of everything else, the ground isn’t level, so everything is topsy-turvy,” says Shannon Taylor, director of art and restoration. “Half my life is spent in bushes or climbing up on rooftops or perched on towers,” to figure out how something is constructed. And when she finds out, it can be a real surprise. Like the Three Men in a Tub set, that was “a mixture of Styrofoam, rusted nails, and sheets of fiberglass.” Sets were made by volunteers who “used whatever materials they had on hand. When you look inside and try to figure out how they were made, it’s like a message in a bottle from the past.”

…the Talking Storybook and the Magic Key were born. Eventually, he realized the technology could be used for wider applications, so he invented the magnetic security card keys that are used in hotels and parking lots.

But the most iconic thing at Fairyland, the one all the kids remember for the rest of their lives, is the Magic Key that activates the park’s talking storybooks. Insert the key in the lock and turn it, and the talking storybook will tell you a story or sing a song.

The keys and the storybooks were invented by Bruce Sedley—aka Sir Sedley, aka Skipper Sedley—who, along with his puppet sidekick, King Fuddle (who later morphed into Professor Fuddle, a weather forecaster who was never right)—hosted popular children’s television shows in the Bay Area in the late 1950s and early ’60s featuring Three Stooges shorts and Popeye cartoons.

In 1957, he visited Fairyland for the first time and was charmed. He started mentioning Fairyland on his show and occasionally broadcast the show on remote location from the park. On one of his visits he noticed coin-operated record players playing nursery rhymes, and he was told they were constantly breaking down. So, using a new, state-of-the-art technology called the tape recorder, he made the first repeating tape loop, and the Talking Storybook and the Magic Key were born. Eventually, he realized the technology could be used for wider applications, so he invented the magnetic security card keys that are used in hotels and parking lots. The first ones were made in his kitchen, using a pasta roller he bought in North Beach.

“There is no doubt that the Magic Key is the single most enduring icon we have in the park,” says Hirschfield. “I constantly hear from thirty, forty and fifty-somethings, ‘I still have my key!’ And I always reply, ‘And it still works!'”

Hirschfield came to Fairyland in 2002, abandoning a lucrative career in the cable television industry. “My employees and I were in New York, producing a fundraiser for a non-profit that was encouraging minority participation in the management ranks in cable, and it was an event that drew over a thousand people. The next day was 9/11. I found myself thinking, ‘I hope the people in the twin towers loved what they were doing.’ And then I asked myself, ‘Do I love what I’m doing?’ It was time to make a change. I wanted to do something that was closer to my heart. I came back here, and the first time I ever looked on Craigslist, there was this job description. It was a major lifestyle change, but my family and I were up for it, and it was the best decision I ever made.”

Among her contributions: beginning the process of systematically restoring all the sets, starting with the Pirate Ship, which had yellow police tape around it because

it was unsafe for kids to play on, replacing Thumbelina’s Tunnel with the Fairy Music Farm, and building Aesop’s Playhouse.

But her proudest accomplishment is Fairyland’s outreach program to the community. “We are completely committed to keeping our entry fees as low as possible [$10], but we appreciate that not every family can afford to come here. So that’s what we fundraise for—to ensure that every family can.”

This year, Fairyland was able to offer 16,000 free or subsidized admissions for Bay Area children and their families. In addition, 2,200 babies, toddlers, and their parents attended this year’s Talk Read Sing event and received books, Magic Keys, tote bags, T-shirts, and 100 free family memberships. Another 2,200 local Head Start children and their families attended Head Start Day, and 391 little ones attended Transitional Kindergarten Day, featuring animal interactions and garden crafts (click here to contribute to any of those programs).

This weekend, Children’s Fairyland will be transformed into Fairy Winterland until December 23. Instead of closing at its usual time, 4 p.m., it’ll stay open until 7 p.m., covered in white by a snow machine illuminated by thousands of tiny sparkling lights. The effect is magical, even for grownups. There will be a puppet version of Beauty and the Beast, and celebrations of a number of holidays, including Christmas, Hanukkah, Ramadan, Diwali, Kwanzaa, Los Posadas, and Chinese New Year.

But the star of the show, of course, will be Santa Claus. Every day, the children will have a chance to meet Santa and in the evening he will lead the little ones through the park in the nightly Festival of Lights Parade.

Santa’s alter ego is Ron Zeno, a kindly giant of a man who jokes, “At six feet two and 368 pounds, I’m the only Santa who has to lose weight every year to fit into my Santa costume.”

And until this year, he was the only African-American Santa, too.

“Everybody’s making such a big deal about the black Santa at the Mall of America this year,” says Hirschfield. “So what? We’ve had Ron for 20 years. He’s the best Santa we could ever wish for. He’s so sweet and gentle with the kids….”

Santa’s secrets of success: No “Ho-ho-ho” (“It scares the bejesus out of little kids,” he explains), no promises (“Never. Not even a suggestion. Don’t go there.”), and no direct eye contact (“That can be intimidating, too”).

“I try to make myself small and not get in their face,” he says. “I want to make sure they aren’t being forced to have an experience with Santa that they’re not comfortable with.”

Despite all the changes in the past 66 years, Children’s Fairyland is still what its founders intended it to be: an oasis of calm in the middle of downtown Oakland where kids can just be kids.

“Every time we do something new we think, ‘Are we channeling the vision of these guys?,'” says Hirschfield. “We’ve done a lot of things they never could have envisioned and are outside their original plan for the park, like our outreach programs for kids in foster care who experience trauma, or horticultural therapy program for autistic kids, and our junior animal caretaker program. But I know this is what they would have wanted for the kids. The latest child development studies show conclusively that play is the essential work of childhood. The research is finally catching up to your two Cal grads. They knew what was the right thing to do, and they were right.”