Ninety-year-old Berkeley alumna Rebecca Contopoulou (born Rebecca Israel) speaks Greek, Italian, French, English, Spanish, and another language that sounds a lot like Spanish but is actually Ladino, a Sephardic language that traces its origins to Medieval Spain.

According to Julia Peck, a PhD student in Berkeley’s Linguistics Department who is studying Ladino, the two languages—Spanish and Ladino—were so intertwined that many Sephardic communities saw them as indistinguishable. Over the centuries, though, differences were accentuated as Ladino-speaking Jews came in contact with other cultures and the language absorbed influences from Greek, Arabic, French, and Turkish—centuries of Jewish diasporic history encoded in language.

For thousands of years, the Jewish community has contained a wealth of different languages and cultures. Besides the commonly thought of Hebrew and Yiddish, there’s also Judeo-Arabic, Judeo-Italian, Judeo-Malayalam, Judeo-Persian, and many more. But they all share a shrinking number of speakers, in part because many, like Contopoulou ’52 MA ’57, were scattered by war and emigration, or killed. This is a profound loss, according to Peck, not only for individuals, but also for cultural history. “A language in many senses can be equivalent to a culture,” she notes. “And when one disappears, you’re looking at a massive loss of cultural information, of relationships between people that were carried out in that language before.”

For this reason, Peck has dedicated her career to preserving Ladino. After working with the Amazigh speakers in Morocco and Zaza speakers in New York, Peck wanted to work with an endangered language in her own community. She had seen the effects of the loss of language in her own family: Her father was never able to converse with his own Yiddish-speaking grandfather. She chose Ladino because she recognized that more focus and resources were being put into Yiddish, especially in the United States.

“As a kid, I only learned ‘Ocho Kandelikas,’ the very famous Ladino Hanukkah song, and knew basically nothing else about the language and felt like that was unfair,” Peck explained. “But also, I could see where my skills could line up to join in language revitalization efforts that already exist in the Ladino-speaking community.”

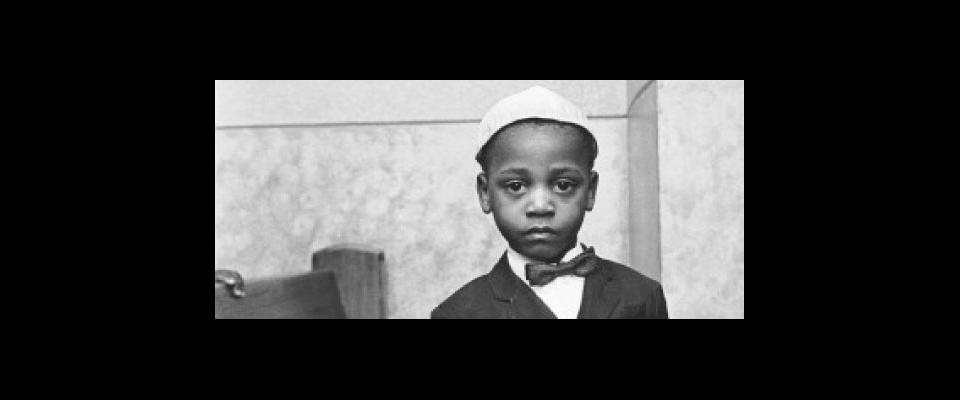

In many ways, Contopoulou’s story is the story of Ladino. Born on Rhodes, then in the Italian Empire, Contopoulou moved at age four to Athens where she survived the Holocaust in hiding before moving to the United States. Besides a couple of years in Greece in the late ’60s and early ’70s, she has spent the past 76 years in the Bay Area.

Asked by her son if she considered herself an American, Contopoulou hesitated. “So to a degree, I am American, but I also am Greek, and I am Jewish. Jewish takes care of everything,” she said.

Andrew Contopoulos (’82) mentioned that he and his siblings were not raised Jewish; they never attended synagogue, they didn’t celebrate Jewish holidays, and their mother never openly practiced Judaism around them. And yet, there were signs of it everywhere in their home: there was a menorah in the entryway; Contopoulou’s family offered me bourekas, a Sephardic Jewish pastry; her sister’s ketubah, or Jewish marriage certificate, hung on a wall; and she told me that the Star of David necklace she wore had probably been around her neck every day since she was married.

Within Contopoulou’s family, as with many families of minority language speakers, Ladino was lost within just a couple of generations. This is a phenomenon Peck explained as the “classic three-generation model of language shift or language loss.”

“It is extremely rare for a community to voluntarily lose their language,” Peck said. “Language loss often means that a community is facing severe discrimination, which forces them to switch or shift languages to survive.”

Contopoulou’s parents spoke Ladino to each other and in their community in Rhodes, but her parents spoke to her in Greek, Italian, and French. Those were the languages that allowed Contopoulou to assimilate to the communities they moved to. Once in the United States, Contopoulou married a Greek Orthodox man and spoke only English and Greek to her own children.

Contopoulou’s family story shows, in one lifetime, the trajectory of Ladino speakers over thousands of years—a story hidden in the makeup of the language. Sephardic Jews have kept their connection to Spain for more than 500 years through their language. But over time, that language took on borrowed words and phrases which are now interspersed throughout the language. Take, for example, the word in Ladino for Sunday, alhad, which is from Arabic’s al-ahad. Orozo/oroza, meaning “happy,” is from the French heureux/heureuse. Buchukes, or “twins,” originates from Turkish’s buçuk, meaning “half.” The Hebrew mazal tov, meaning “good luck,” or “congratulations,” is mazal bueno in Ladino.

Peck shared a quote from the late Klara Perahya, a Ladino language activist and writer from Istanbul and creator of a Turkish-Judeo-Spanish dictionary, which she said illuminates this idea of linguistic borrowings:

Judeo-Spanish:

“Muestros avuelos, de siempre siempre, tuvieron la manya de ispanizar las palavras ke tomavan. Kuando tomavan una palavra turka, o la desformavan, o la ispanizavan. Par egzampl, de kullanmak, izyeron kullanear. Este modo aziyan una palavra, no solo espanyola, una palavra djudiya.”

Peck’s translation to English: “Our ancestors always had the habit of hispanicizing the words they took. When they took a Turkish word, they either modified it or hispanicized it. For example, from kullanmak (‘to use’) they made kullanear. That way, they were making not only a Spanish word, but also a Jewish one.”

Through her research, Peck aims to show how, because of these borrowings, Ladino is far from dead. “It’s been sentenced to death for quite a long time and it hasn’t died,” Peck said. The borrowings that continue to be added to the language show it is still alive. She added that the metaphor of language death is itself problematic. Linguists prefer to say that the language is “sleeping”, she explained, “because we know languages can come back.”

Part of Peck’s Ph.D. work will focus on revitalizing and preserving Ladino. Previously, while getting her master’s at Oxford, Peck worked with the Ottoman-Turkish Sephardic Cultural Research Center in Istanbul to support the revitalization efforts already started by the Ladino-speaking community there. These efforts include a Ladino newspaper (the only one in the world), theater, music, online language courses, and an archive of interviews with native speakers called the Ladino Database Project.

The coordinator of the center, Karen Gerşon Şarhon, told Peck that the pandemic caused a linguistic renaissance. More young people are interested in learning Ladino than ever, despite the fact that the youngest native Turkish Ladino speakers were born in 1945. Peck said this has created a turning point where the Jewish community gets to decide to support and preserve this diversity in the Jewish community.

Now, at Berkeley, Peck plans to work with the research center to develop teaching resources, including children’s books and home language-learning kits, to help people make the language visible in their homes.

Peck chose Berkeley for her Ph.D. partly because of the program’s emphasis on language revitalization efforts, as well as its focus on the need to give back to the communities that linguists are working in.

“We have examples of professors and students working on dictionaries and websites and things that are more accessible to nonspecialists but who might have a special interest in a particular language,” said Isaac Bleaman, an assistant professor in the linguistics department and Peck’s advisor.

While at Berkeley, Peck hopes to, in collaboration with the research center, make sure its Ladino Database Project is preserved in the California Language Archive, a physical and digital archive begun in 1953 as a way to preserve Indigenous languages, which has since grown into one of the largest such repositories in the world. The archive, full of handwritten notes, tapes, and other forms of recordings, is tucked away into two unassuming rooms on Berkeley’s campus, yet is home to around 500 named language varieties. The archive has also started the process of digitizing all of the physical recordings and notes it holds.

“It would be amazing for any Ladino speaker, any Sephardic person, any Jew, anyone in the world to be able to access these recordings of speakers and use them to learn Ladino,” Peck said.

__

One winter evening, I joined Contopoulou and her family at their house in the Berkeley Hills to listen to a recording of Contopoulou’s mother speaking and singing in Ladino. The cassette was recorded in the ’80s. It was the first time that Contopoulou had heard her mother speaking Ladino since 2008, when she passed away at the age of 102.

At first, Contopoulou did not recognize the voice on the tape. “That’s the language,” she said, “but I don’t know if that is my mother.”

But a few minutes later, listening to her mother sing “Morenica,” meaning “little brown-haired woman,” Contopoulou held the recording close to her ear and leaned back on the couch, tears forming in her eyes. “That’s my mother,” she said as she began to sing along, the words coming to her immediately as if no time had passed.