Molly Kawahata lives in Bozeman, Montana, so that she can climb frozen waterfalls in the frigid Rocky Mountain winters. The Cal alumna (’11) started her mountaineering career on less vertical objectives but soon found herself wanting more.

“I was like, ‘Oh, I’m bored of walking around glaciers. I want to get up there.’ And that was ice climbing,” Kawahata said. It’s a pursuit that has some parallels to her other passion: climate action.

“You don’t try to climb something that’s literally impossible,” says Kawahata at the beginning of The Scale of Hope, a new documentary by outdoor retailer Patagonia. “You have to know that you could get to the top. In the climate movement, we need to do the same. When we lead with hope, everyone can be a part of it.”

The Scale of Hope weaves Kawahata’s views on climate action and her experience with bipolar II disorder as she prepares for an ice-climbing expedition in Alaska. A former White House climate advisor in the Obama administration, Kawahata has a different attitude about climate change than many activists—one infused with her old boss would call the audacity of hope.

At Berkeley, Kawahata studied under George Lakoff, Berkeley professor emeritus of linguistics, whose ideas strongly influenced Democratic politicians in the early 2000s. From him, she learned that emotions like fear, guilt, and shame are not motivating.

“We have this idea that you could scare people into action,” Kawahata says. “But instead it makes people take up less physical space and they feel paralyzed. It has a freeze response.”

If action is the desired outcome, Kawahata insists hope is the emotion climate activists should be aiming for. Changing the narrative from shame to hope is all part of what Kawahata calls reframing, something that comes up often in her presentations. Another thing she wants to reframe is the notion of the carbon footprint.

“A lot of people don’t know that the individual carbon footprint was popularized by the fossil fuel industry,” Kawahata explained. “If you think about what the carbon footprint is, it’s taking a system based on fossil fuels like our electricity, transportation system, even parts of industry, and it’s apportioning blame onto the end users who are forced to use it.”

An example Kawahata gave in the film was Berkeley’s own carbon footprint calculator, which tells users living in nearby Richmond—next to an oil refinery—that they should reduce their impact by doing things like getting an electric vehicle and printing double-sided, something she finds absurd.

“It’s kind of a bizarre concept to blame the end users who are living in the only system they’ve been given,” she says. “When you hear people say things like you’re a hypocrite because you care about climate and you live a normal modern life, what this does is it pushes climate guilt, another concept pushed by the fossil fuel industry on individuals.”

Of course, Kawahata stresses, greening your lifestyle is great. But it’s often only the upper swath of society that has the means to do so. In order to actually create change, she says, the most effective action is registering people to vote and affect policy. Her case in point: Passage of Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, lauded as the most significant climate legislation in history, was only made possible after Georgia flipped from red to blue, thanks to historic rates of voter registration.

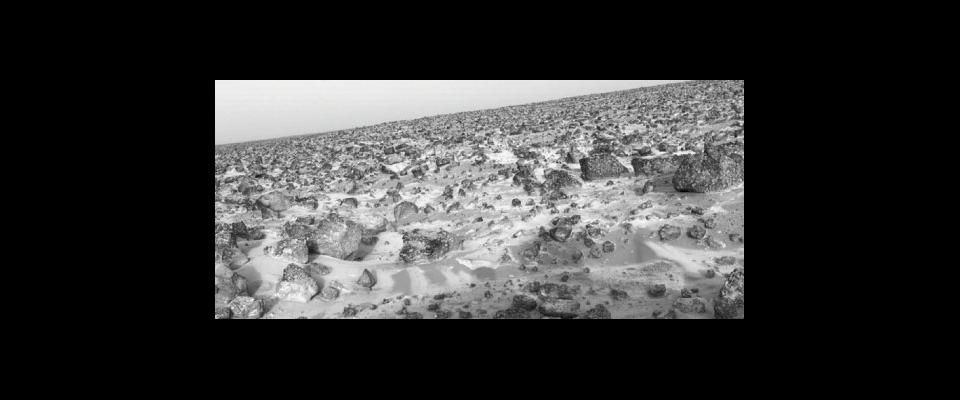

The second half of The Scale of Hope follows Kawahata’s trip to Alaska, where she and another ice climber are thwarted by the stormy weather. “The scale is unrelatable,” she says about the Alaska mountains, and the same could be said of the climate challenge. But last spring, she returned—and succeeded. Kawahata isn’t one to back down from a tough climb.