Now that a few days have passed, the decision by National Football League owners to fine teams with players who do not “stand and show respect to the flag and the [national] anthem” hardly seems Solomonic; rather than ameliorating tensions, it almost assures another football season marked by player protests, discord both inside and outside the League, and acrid tweets from President Donald Trump.

The rule, which requires players to stand during the national anthem or remain in locker rooms until the anthem has been played, is designed to appease all involved parties but satisfies no one. And the new policy reveals more than fuzzy thinking, says Cal sociology professor emeritus and paid consultant for the 49ers Harry Edwards. First, says Edwards, it shows that owners are willing to cave to racist “dog whistles” by a provocative and autocratic chief executive. Second, it demonstrates a plantation mentality, a bumptious assumption that NFL players—most of whom are black—are virtual chattel whose civil rights can be abrogated at will.

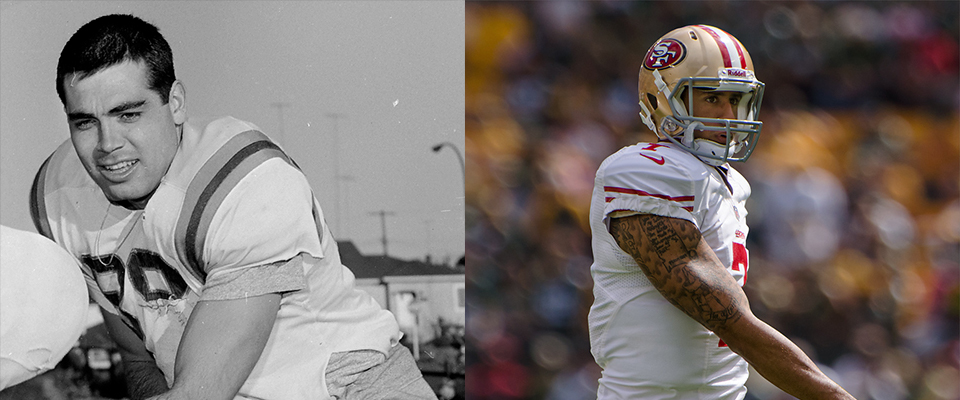

“In the end, it just injected new life into a fading movement,” says Edwards, noting that the “take a knee” national anthem protests that started with San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick in 2016 were intended to highlight police brutality against people of color. “There is a natural cycle to activist movements that typically ranges from three to six years. The [national anthem] protests had begun to fade, superseded by the #MeToo movements and the student actions for gun control following the [Marjory Stoneman Douglas] high school massacre in Florida. But the owners’ decision put the players’ protests back in the news. The results they achieved are precisely opposite of the ones they wanted.”

Edwards was the prime mover in the Olympic Project for Human Rights, which inspired African-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos to display black power salutes from the winners’ podium at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. (Smith and Carlos competed in the 200 meter sprint, respectively winning the gold and bronze medals.) Edwards has served as both an analyst of the role black athletes have played in social justice movements and as a mentor – and sometimes goad – to the athletes themselves. He observes that that the national anthem protests are merely the latest episode in the long history of black athletes galvanizing political action over racial inequities, from Jack Johnson to Jesse Owens, Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali, Smith and Carlos and now, Kaepernick et al. NFL players kneeling during the anthem didn’t start Black Lives Matter, but they focused the message, bringing it to one of America’s most popular forums: the pro football stadium.

“So now the owners took this declining movement, put it on life support, gave it an adrenaline drip, and ensured it will be more powerful than ever when the [upcoming football] season starts,” Edwards says. “The upside is that it could provide a new opportunity for professional sport team owners and athletes to work with people in affected communities to get something done. In Oakland, for example, if Steph Curry or Kevin Durant or Klay Thompson asked for a meeting with the Chief of Police, they wouldn’t be told to get lost.”

Many NFL owners “are wealthy, entitled and arrogant, and they essentially view their players as property, not human beings with rights guaranteed by the Constitution.”

The downside, continues Edwards, is that a revitalized national anthem protest “gives Trump another shiny object to distract people from critical issues, including the duplicitous stupidity and corruption in the executive branch, during a critical election year.”

Further, the owners’ decision has created new and divisive tension points between players and coaches and among the players themselves. The owners, says Edwards, are holding the coaches responsible for any of their players who take a knee.

“The owners are dumping everything on the coaches, saying ‘This is your shop, you handle it,’” says Edwards. “Some coaches will try to force their players to comply, and others will allow them to do as they see fit, and pay fines if necessary. At the same time, some players are saying, ‘I want to stand to honor the flag and the soldiers who fought for it’. Others are saying, ‘I’m a patriot too, and I want to kneel to honor what is most significant about the flag and the soldiers who fought for it, namely the right to protest injustice.’ And at the same time, nothing will put a spotlight on the whole dispute more than protesting players running out on the field from the locker room after the anthem has played. And all this will be happening as coaches and teams try to build solidarity – which is critical, of course, to winning games.”

Part of the problem, Edwards explains, is that many NFL owners “are wealthy, entitled and arrogant, and they essentially view their players as property, not human beings with rights guaranteed by the Constitution. And they’re ignorant of history. They don’t or won’t understand the context of these actions, the long national narrative of racial injustice, and what the players are saying now: This land is not free. My people are not free. It’s a carryover from 400 years of slavery and oppression. [NFL team] owners are acting like plantation owners, insisting that any act of ‘rebellion’ must be squelched.”

That said, NFL officials and team owners are just beginning to realize the financial repercussions of the new rule. According to Edwards, online petitions already are circulating that call for sponsors like Nike, Ford, Hyundai, Anheuser-Busch, Bose, and Under Armour to sever ties with the League because of the kneeling ban.

“This is really starting to take off, and when the team owners lose money, I assure you they’ll pay attention,” Edwards says. “It’s going to be very difficult for a sponsor to support a league that strips a player of his First Amendment rights, to support a rule that ultimately may be proven illegal in the courts.”

To make matters even more complicated, says Edwards, the new decision to enforce standing during the anthem applies to all employees of NFL teams – not just the players. That will make enforcement of the new rule difficult, to say the least. In any given game, spectators can observe team employees and staffers doing various things during the national anthem other than standing at rigid attention.

“What about the groundskeeper who’s hurrying to fill a gopher hole on the field before kickoff?” asks Edwards. “He’ll need to fill that hole, because if a linebacker, say, twists or breaks an ankle on a play, that could be a multimillion-dollar incident. So how are you going to enforce that, and determine who triggers a fine, and why?”

“It’s not critically important whether [Kaepernick] ever plays again, any more than it would’ve been critically important if Rosa Parks had been given a free lifetime pass to ride Montgomery’s buses.”

In the meantime, tensions between owners and players will inevitably increase, Edwards says, given it’s a black League that will only become more black with time.

“Right now, about 70 percent of players are black,” Edwards continues, and “that will increase to about 80 percent in a few years. When you have white players like Peyton Manning and Tom Brady and Drew Brees saying they’re not going to let their sons play football, who’s left? I’ve talked to African-American mothers whose sons are playing college football, and they’re certainly not talking about pulling their kids out of the game. They’re saying pro football is the one way out for their kids, that it’s better they risk neurological damage 25 years from now than having their heads blown off in a street confrontation now.”

But what about the guy who started it all, and who lost his career as a result? Colin Kaepernick has not played since the start of his free agency in March of last year, and remains unsigned. It’s quite likely he’ll never play pro football again. He wants to play, says Howard; but he won’t be devastated if he doesn’t.

“He’s working out every day, and he’s in the best shape he’s ever been,” says Edwards, who knows Kaepernick well. “He’s ready. But it’s not critically important whether he ever plays again, any more than it would’ve been critically important if Rosa Parks had been given a free lifetime pass to ride Montgomery’s buses. We need to remember that 378 black men, women and children have been killed by police since Kaepernick initially protested. What he did is so much bigger than whether he is signed or not.”

When Kaepernick first knelt in 2016, Edwards says, “I went up to him and asked him to sign his shoes and his jersey and give them to me. Then I sent them to the National Museum of African American History and Culture at the Smithsonian, where they’re now on display. Kap asked me why I was doing it, why I thought this thing was going to be so big. I said, ‘Because the flow of history is inexorable.’ He’s part of that history now, and he knows it.”