When did going to college get so stressful?

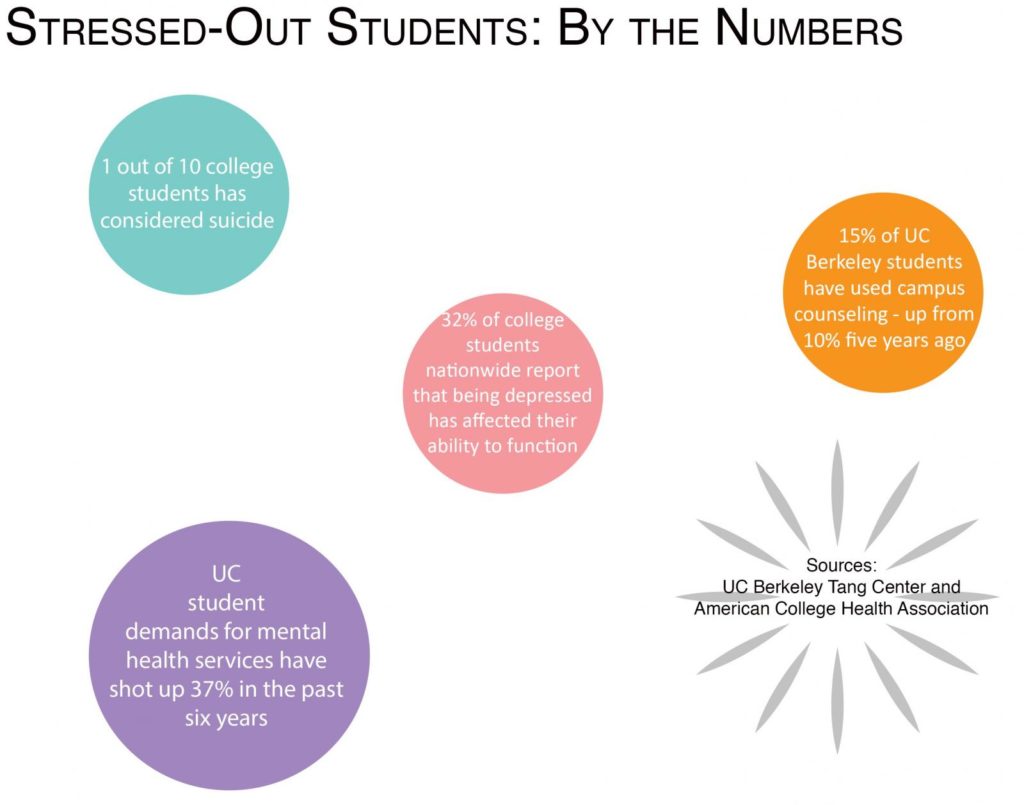

Nationwide, more students than ever say they feel anxious and depressed—at some point last year, almost a third were so depressed that they said they found it hard to function, according to the American College Health Association. The problem is particularly acute at top tier schools: About 15 percent of UC Berkeley students have used campus counseling services, up from 10 percent five years ago. At UCLA, the number has jumped to 20 percent.

And those are just the ones seeking assistance. “The percentage of students dealing with emotional problems is much higher than the percentage getting help,” says Jeffrey Prince, director of the Berkeley campus’s Tang Center. Although the health center is trying new strategies to reach them, it is already stretched to its limits—and so, too, are mental health services at all University of California campuses.

UC student demand for such services has surged 37 percent in the past six years, according to UC health system officials who briefed UC Regents on the crisis. News coverage of the Regents’ meeting focused on the threat of tuition increases, but the Regents also were asked to raise student services fees, partly to pay for hiring more counselors.

At Berkeley, it can take students two weeks to get a non-emergency appointment with a counselor. Across the UC system, students sometimes must wait up to seven weeks.

What explains the demand?

“There is “no one smoking gun,” Prince says. Students are more aware that help exists, some feel less stigma asking for it, and more enter the university with diagnosed mental health problems. One out of four students using UC counseling centers are on medication for mental health issues.

But students at Berkeley also say they feel the pressure ratcheting up: academic competition, extracurricular activities, resume-building internships, jobs and rising bills. They describe being excited and challenged on campus, but also daunted about by heightened expectations. What would be the result, some wonder, if their parents knew they were floundering? After working so hard to get in and succeed, what would happen if they fail?

“We get many students who compete in high school and often come to the university with their identity connected to their academic success,” says Prince. “When they encounter a bad grade or a failure, or are no longer at the top of their class, their identity can be challenged.”

“Depression and anxiety are products of the environments we are in, I don’t think we can safely say Berkeley is a healthy environment.”

The center reminds students to take care of their health and recognize the signs of serious stress: trouble concentrating, changes in eating or sleeping, or problems with relationships. But some say that pressure, even if it doesn’t derail them, is a constant in their lives.

Before dashing to class one day recently, two students talk about the well-known triangle of social life, academic work and sleep. It’s only possible to do two of those the right way. What do they sacrifice?

“Sleep,” they say, high-fiving in agreement.

It is the setting for what one Berkeley student leader—who herself has struggled—calls “the perfect storm of depression and anxiety run amok.”

Mon-Shane Chou, academic affairs vice president for the Associated Students of the University of California, felt the financial and academic stresses pile on after she got to Berkeley. She had gone to a competitive high school in the San Gabriel Valley where, she recalls, the popular kids were not cheerleaders and athletes but over-achievers taking 5 AP classes and spending their free time in model U.N. sessions and SAT prep courses.

“I was not on that level,” says Mon-Shane, who went on to excel in community college, win scholarships and transfer to Cal. Once there, she worried not only about doing well in her classes, but about affording her apartment and meals. She took on student government work and a part-time job. At the time, her schedule didn’t seem extreme compared to her classmates, many of whom added sports and internships to the mix.

Soon Mon-Shane, who had dealt with anxiety and depression in the past, knew she needed help and went for counseling. She said it has helped her find balance. She moved into a coop, where expenses are lower, and she’s learning to say no so she isn’t over-committed. In student government, she advocates for more access to mental health services, particularly for students who feel marginalized even in a school as diverse as Berkeley.

“Depression and anxiety are products of the environments we are in,” she says. For some students, she says, “I don’t think we can safely say Berkeley is a healthy environment.”

At Tang, the counseling center offers free drop-in and 15 minute triage calls. Students who wait for appointments can receive up to eight sessions of counseling—five free and the rest with a $15* charge. For longer-term or specialized needs, the center refers students elsewhere, to private therapists or community resources. (Berkeley has more community options than many UC campuses; students at UC Merced, for example, may be forced to travel a couple of hours away for appropriate mental health care.)

Cypress Lynx says someone should have warned her as a freshman: “You’re going to have a hard time this year.” A top student at her small Oakland high school, Lynx was devastated when she failed a math class her second semester at Berkeley. As her grades slipped, so did her mood—she felt increasingly isolated.

“I thought I was a smart kid who didn’t need any help,” says Lynx, who worried she’d lose her scholarships. “But everyone here is from the top 10 percent of their class. I hear about stress so much. Students here are so competitive.”

Lynx, who also began battling an eating disorder, finally went to the counseling center. She moved to a calmer dorm and learned to push back against her notion that she had to be perfect. Now, in her third year and pursuing a double major in nutrition and molecular biology, she hopes after graduation to help others suffering from disordered eating.

For now, she’s learning to encourage classmates to ask for help. She was one of 10 students attending a recent suicide prevention program at the engineering school. Tang psychologist Aaron Cohen covered myths about suicide —that it can’t be prevented and that talking about it makes it more likely—and advised them on recognizing direct and indirect warning signs. He told them to be persistent about suggesting help, and be willing to accompany friends to the counseling center. Finally, he asked them to role-play, taking turns being in crisis and offering help. It’s a touchy topic: There were some nervous giggles at first, and one student declined to participate, instead silently listening to her partners.

Cohen also reassured the group that most students are not in danger of hurting themselves: Actually, college seems to have a protective effect on students, who have a lower overall suicide rate than nonstudents the same ages. But 10 percent each year will have suicidal thoughts.

“That’s 3,500 students here,” Cohen said, “so think about that number.”

The presentation at the engineering school is an example of Tang’s outreach—not only does it provide counseling, stress management programs and support groups, but it also has opened satellite offices around campus. One goal is to reach students who otherwise won’t come to see a counselor. Some students face cultural barriers or fear a stigma for seeking help—include Asians, Latinos, Middle Easterners, veterans and undocumented immigrants. Some students may fear being labeled “crazy.”

It’s “the culture of Berkeley. When you see kids doing six things at one time, you say, ‘Oh, I’m only doing four. Am I going to be successful later in life?’ “

The counseling center staffs satellite centers in student government offices, International House, and other student gathering spots. Counselors also have been training faculty, graduate students and residence assistants to better spot signs of stress. They make presentations at freshman orientation. Some will travel to Shanghai as part of an exchange program with counselors there, exploring how to help the fast-growing population of Chinese students at Berkeley.

Dawn Lee Tu, director of the Asian Pacific American Student Development Office, says many students respond to smaller environments where they can drop in to talk, nap, or bring up what’s bothering them. On a big campus, where there are few central gathering spots, her office is like a living room.

“In one semester here I had two mental health crisis cases where I had to have a series of conversations with students, which ended with me walking with them to (the counseling office),” she says.

Just the previous night, she had convinced a student who was depressed about poor performance in a class to see a counselor at a satellite office there. “What works is to develop a relationship,’’ Tu says. “Once that familiarity is there, you talk about support. It’s got to be framed so it’s not about mental health. Anything related to mental health (might be seen as) a disorder, something is wrong with you. I use the emphasis of academic stress and advising.”

Often students are so over-committed they don’t have time for drop-ins or outreach workshops. One program, Tea and Chat, aimed at Asian students—who are 40 percent of the student body but make up only 24 percent of those seen at Tang—was scrapped because too few students showed up.

“You can advertise, have food and they still don’t come,” says Tang assistant director Susan Bell. “Many of our students are working and they are trying to get through school by taking lots of credits. They have outside activities. It’s hard for them to take care of themselves.”

To Mandona Mostofi, a senior who volunteers at Student to Student Peer Counseling, that is “the culture of Berkeley. When you see kids doing six things at one time, you say, ‘Oh, I’m only doing four. Am I going to be successful later in life?’ ”

Volunteers aren’t therapists, but they do help students brainstorm stress-reducers—offering a friendly face, bowls of stress balls, chocolate – and, before finals, puppies and paint throwing parties. How does she manage it herself when she also works in a local elementary school, has an externship at Napa State Hospital, leads a student-run class, is a peer counselor, and carries a full load of classes? Partly, she says, by choosing activities she really cares about, and by trying to maintain perspective.

“I was always the best, and now there are so many better than me,” she says . “You learn not to fear and to enjoy. You learn that not being on the top all the time is ok.”

There is no indication yet whether UC Regents, in the midst of budget and tuition discussions, will agree to the request before them and allocate more student fees to campus mental health centers.

“What is our Plan B?” says Gina Fleming, medical director for Student Health Insurance Plans, who also briefed the regents in January. “Unfortunately, there is no other money….If there is no funding, we will have to go back to the drawing board. It’s not an issue where we can say, ‘Oh, well we tried.’ ”

* This corrects at earlier version of the story.