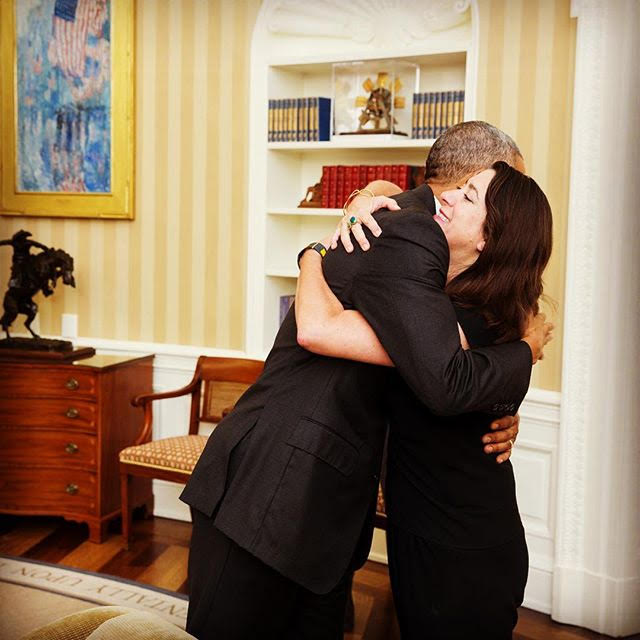

Most of the people who follow the President of the United States wherever he goes are there to protect his life. But Hope Hall has a different job: to document it.

For the last six years, she’s been Barack Obama’s presidential videographer (think of her as the national fly on the wall). She doesn’t shoot videos for the official record; that’s the job of the White House Communications Agency, which documents every public event in which the President participates. Her assignment is to film the President in his more informal moments.

“My job is more editorial, in that my work is more often handheld and behind the scenes, rather than on a tripod from a riser,” she says. Everything she shoots will go to the National Archives and, eventually, the Obama Presidential Library.

Among her recent work: President Obama launching marshmallows at the White House Science Fair; surprising tourists on the Ellipse, the park that lies south of the White House gates; handing out special White House M&Ms to trick-or-treaters on Halloween (and getting a big kick out of one little kid dressed as a lame duck); shooting the breeze (and some hoops) with the University of Connecticut’s NCAA champion women’s basketball team; making surprise phone calls on Mother’s Day to the moms of some of the people who have written him; answering questions from a class of White House interns.

“But our single most successful piece of content, both in terms of reach and engagement, was a video of the President and the First Lady dancing with a 106-year-old woman in the Blue Room. It not only got the most hits by far, it got the most comments, shares and retweets.” Hall and the video team also produce a weekly compilation of the greatest hits from the previous seven days called West Wing Week, narrated by White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest.

“There’s always a tradeoff between being close enough to get the right shot and not being intrusive.”

“I have the best job ever, by a margin of a zillion,” she says. “Honestly, just about every day on the job I have a moment where I get goose bumps and have to have a little freak-out in a quiet corner. I still can’t believe it’s real.”

But being so up-close and personal 24/7 presents unique challenges.

“There’s always a tradeoff between being close enough to get the right shot and not being intrusive. So I try to anticipate what effect my presence will have; and if I think I’ll impede the process, I’ll recuse myself. You could argue that just being there affects the dynamic—the Heisenberg principle, which says just the act of observing something will change whatever is being observed— so in practice I constantly have to strike a balance, and balancing these two things is a fulltime intellectual, emotional and spiritual job. Luckily for me, I find it fascinating.”

“When I was a freelance documentary filmmaker before I came here, I would spend time, sometimes hours, with the subject before turning on the camera so we would have a total understanding of this problem. I have that conversation constantly in this job, too; but it’s all internal, not with the President. We just don’t have time. So a deep level of trust comes with the job.”

So what’s he really like?

“That’s the number one question I always get, more than all the others combined. Of course, you can never experience what it’s like to be another person, but I think the video we made at Stonehenge is the closest to evoking what his actual inner experience was like at that moment. Even then, I gave him some space.”

Washington gamely endured sitting after sitting because he felt they were important in unifying the new country.

Heads of government have understood the value of images as instruments of power since the days of ancient Rome, when each new emperor established his authority by minting a new set of coins with his likeness. Medieval monarchs used their official portraits for the same purpose (Elizabeth I’s chief minister, Lord Burghley, went one step further and issued stencils of her to local artists with orders to use them or else, which is why all her portraits look the same, no matter what age she was when they were painted).

George Washington and his most famous portraitist, Gilbert Stuart, loathed each other—now you know why Stuart’s portraits of him are so unflattering— but Washington gamely endured sitting after sitting because he felt they were important in unifying the new country.

The first president to be photographed was John Quincy Adams, who sat for a daguerreotype years after he left the White House. The first to be photographed during his presidency was William Henry Harrison, whose likeness was captured at his inauguration in 1841. Harrison caught a cold at the ceremony that quickly turned into pneumonia, and he was dead 30 days later. But the photo has been lost to history. The oldest surviving photograph of a sitting president is a snapshot of James K. Polk taken in 1849.

Only ten years later, the technology had advanced so fast that photographs were essential for every politician, none more so than Abraham Lincoln, a frequent visitor to Matthew Brady’s photo studio, who said, “Brady’s photographs and the Cooper Union speech (aka the “House Divided” speech) made me President.”

Later presidents were quick to exploit the new medium, especially Theodore Roosevelt, who ordered the front row seats at all his rallies to be reserved for newspaper photographers.

But photographers still remained looking in from the outside until the presidency of Theodore’s fifth cousin, Franklin D. Roosevelt, when a photographer was finally made part of the White House staff. But the person who made it happen wasn’t Franklin; it was Eleanor.

She was riding her horse in Washington DC’s Rock Creek Park one day when she was spotted by Abbie Rowe, a laborer for the public roads bureau. He pulled out his trusty Brownie camera and took her picture, starting a conversation that blossomed into a friendship. She got Rowe a job as a photographer for the National Park Service, and soon he was transferred to the White House with a new assignment: photographing the President.

But since he was on the Park Service’s payroll, not the White House’s, he is not counted as the first White House photographer. That distinction belongs to Cecil Stoughton, who was hired by John F. Kennedy in 1961.

“This is a history-making moment, and while it seems tasteless, I am here to make a picture if he [LBJ] cares to have it.”

In addition to Stoughton, JFK used other photographers from time to time, including Stanley Tretick, whom he called into the White House when Jackie was away to take pictures of the children, including the iconic photo of John-John peeking out from under the presidential desk in the Oval Office.

But it was Stoughton who was traveling with JFK on that fateful trip to Dallas on November 22, 1963; so he was the one who took the iconic picture of Lyndon Johnson being sworn in aboard Air Force One as Lady Bird and a shell-shocked Jacqueline Kennedy looked on.

According to an interview Stoughton later gave to Esquire, LBJ’s staffers initially tried to block him from taking the picture. But he told them, “This is a history-making moment, and while it seems tasteless, I am here to make a picture if he [LBJ] cares to have it.” There was so little space in the cabin, he had to ask Lyndon, Lady Bird, and Jackie to back up, which is why Jackie’s blood-stained skirt is out of the frame.

That event convinced LBJ of the value of a White House photographer, and he hired Yoichi Okamoto, a USAID shutterbug he had met when he was Vice President. Okamoto accepted on one condition: he wanted unfettered access to the President, not the stock grip-and-grin handshake photos.

Johnson agreed and, to the astonishment of his aides, gave Okamoto permission to walk into the Oval Office at any time without being announced. Okamoto photographed him holding meetings from his bed in the morning, getting his hair cut, meeting with notables such as Robert Kennedy, Richard Nixon and Martin Luther King, pressing the flesh with voters, and howling duets with his dog, Yuki.

Things reverted to grip-and-grin under Johnson’s successor, Richard Nixon, who severely restricted his photographer, Oliver Atkins. “Ollie had very limited access,” Gerald Ford’s photographer, David Hume Kennerly, told The Statesman. “This will give you some idea: The most requested photo of his is Nixon with Elvis Presley.”

George H.W. Bush trusted his photographer, David Valdez, so much, he allowed him to be there even during the most painful moments

Kennerly had a much better relationship with Ford. “At the end of the day, President Ford almost always invited me to come up and have a drink,” he told National Geographic.

Ever the contrarian, the next president, Jimmy Carter, didn’t have any photographer at all. (He offered the job to Tetrick, who turned him down, telling the New York Times, “I didn’t feel he wanted an intimate, personal photographer around him.”)

But Ronald Reagan, an old Hollywood hand, didn’t need to be convinced of the power of pictures. His Chief Photographer, Mike Evans, supervised a growing staff that included a young man named Pete Souza, who would become Barack Obama’s Chief Photographer almost three decades later.

“Reagan was close to 50 years older than me,” Souza told Digital Photo Pro. “Now I’m a few years older than Obama.”

George H.W. Bush trusted his photographer, David Valdez, so much, he allowed him to be there even during the most painful moments, including the election night phone call to Bill Clinton to concede the race.

“All of it depends on the president having someone shadowing him all the time, how comfortable they are having someone around,” Clinton’s photographer, Bob McNeely, told The Statesman. “Bill Clinton liked having people around.”

Michael Evans, Chief Photographer during Reagan’s first term, completed the transition from black-and-white to color. Eric Draper, who worked for George W. Bush, switched from film to digital. And when Barack Obama chose Pete Souza as his Chief Photographer in 2009, he also tapped New York-based filmmaker and critic Arun Chaudhary, who had worked on his 2008 campaign, to be the first White House Videographer.

Meanwhile, Hall, who graduated from UC Berkeley in 1991, had moved to Manhattan, where she was teaching algebra, making award-winning documentaries, and running a community garden. Then 9/11 happened.

“Like so many, my life has a before and an after that day,” she says. “I had always had an activist bent, growing up keenly aware of and mobilized by staggering inequality and injustice around me.” So she began as she put it “working within the confusing landscape of the blended marriage of creative non-fiction filmmaking with activism.” She did political organizing, marching, and she documented those marches on 16mm film.

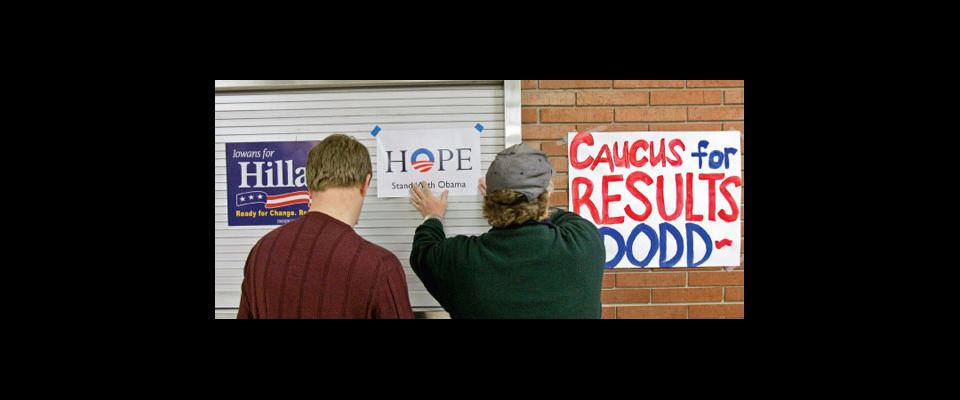

“Then came Barack Obama. Hope and change.” She worked on a 2006 documentary on then-Senator Obama, anticipating that he might run for President in 2008. She signed up as a field organizer in New York.

“You know the story well by now: He won Iowa, and everything changed.” She joined the campaign’s New Media team after Obama won. “Eight of us from New Media took on creating the initial reworking of whitehouse.gov. But by Inauguration Day, I was ready to return home to my life, to my own work, while one of my colleagues on the campaign, Arun Chaudhary, was ready to stay on and help create the position of Presidential Videographer.”

Two years later she was hired back to make the reelection announcement video, and Hall found herself filming the President as he announced his official candidacy for reelection. “I couldn’t imagine! Setting foot in the White House? Me? And then in May 2011, when Arun left to pursue other projects, I came on as the new Presidential Videographer. That was almost six years ago, and every day still feels like a dream.”

She credits two influences from her school days for helping make her who she is today. One was Fran Kondziela, her English teacher at Roger Ludlowe High School in Fairfield, Connecticut, who brought her out of her shell by casting her as Scout in the school production of To Kill A Mockingbird and encouraging her to enter the American Legion National High School Oratorical Contest, where she made it as far as the semifinals, gaining more confidence and earning enough prize money to supplement the grants, loans and work study that paid her way through Cal.

The other was Cal itself. “It may come across as a cliché, but sometimes truisms get repeated over and over because they are actually true. And I will say that the genuine dedication to freedom of expression, based on a deep commitment to critical thinking skills that I [learned] during my years at Cal, influence many of my thoughts, behaviors and attitudes. President Obama repeats this one quite often, and I feel like it says all this in another, pithier way: ‘Everyone can be kind, and everyone can be useful.'”

So what’s the next chapter after a new president takes over on Friday?

“I’ll go back to making documentaries. But I’ll never lose contact with my colleagues; it would break my heart if I did. This is the first full-time job I’ve ever had; I’ve always been a freelancer. You work closely with people on freelance jobs, too, but it’s short-lived. There’s a different rhythm and beat here. I’ve been working with my colleagues for six years, and they’re like family now, including the Secret Service agents. No way I could imagine not keeping in touch, and we’ll probably be making stuff together for the rest of our lives. Anyway, that’s my hope.”