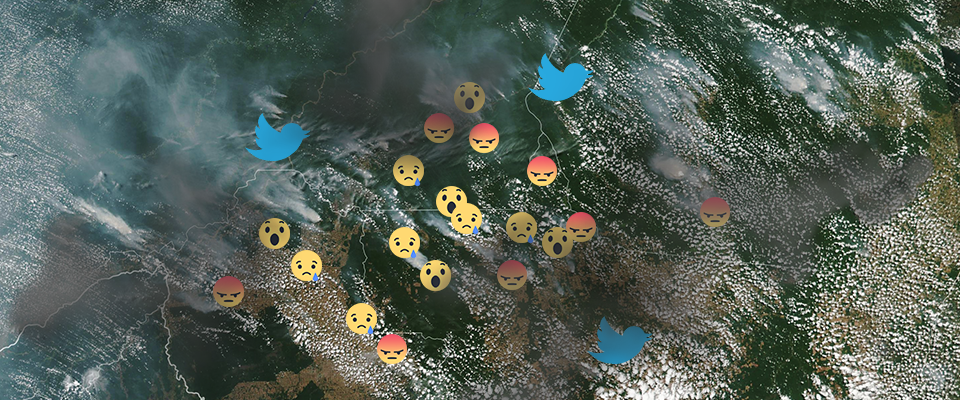

In late August, the Amazon was aflame, and so was social media. Everyone from regular citizens to celebrities and politicians wanted to express their outrage. But in the rush to retweet and regram, some people forgot to fact-check.

French president Emmanuel Macron tweeted a more-than-20-year-old photo of the burning Amazon. Actor Leonard DiCaprio shared the same photo on Instagram. Soccer star Cristiano Ronaldo tweeted a photo of a burning forest that wasn’t even taken in the Amazon. On Twitter, meteorologist Eric Holthaus cited a claim suggesting the current fires were without precedent in the last 20,000 years. (In fact, the situation in the Amazon was worse just twenty years ago, peaking in 2005 when more than 150,000 fires burned through the world’s largest tropical rainforest.)

The longstanding and oft-tweeted claim that the Amazon acts as the “lungs of the Earth,” producing 20 percent of our oxygen? It’s simply incorrect, says Jeffrey

Chambers.

The point here is not that public outrage is unwarranted, but that in a world panicked by a looming climate crisis, partial knowledge mixed with our unchecked sharing on social media is a recipe for misinformation on a grand scale.

Take for example, the longstanding and oft-tweeted claim that the Amazon acts as the “lungs of the Earth,” producing 20 percent of our oxygen. It’s simply incorrect, says UC Berkeley geology professor Jeffrey Chambers, who has been studying tropical forests and climate change for 25 years. Chambers explained that, while photosynthesis produces oxygen, an equal amount of oxygen is consumed when plant matter in the rainforest dies and decomposes. Regardless, Earth’s atmosphere has plenty of oxygen. Humans can mess up the planet in a lot of ways, Chambers explained, but “we can’t mess with oxygen.”

We can and have, however, messed considerably with atmospheric carbon levels, which are largely responsible for increasing global temperatures. This is where the Amazon plays an important role.

Every year, humans emit about 12 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere, primarily from burning fossil fuels like coal and oil. Chambers estimates that the Amazon captures and stores about 900 million tons of that carbon, accounting for about 15 percent of the planet’s total carbon sequestration capacity. “If we reforest [the Amazon], then it has the capacity of being a very large [carbon] sink,” Chambers said. “In fact it could be one of the primary ways we try to tackle this carbon crisis that we have.”

Deforestation has the opposite effect. The burning of biomass and conversion of forest to agricultural production release some two billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year—around 17 percent of the global anthropogenic (i.e., human-caused) CO2 emissions.

The second way the Amazon helps cool the planet is by acting as a giant water pump, said Jennifer Holm, research scientist at Berkeley Lab. When it rains, the tropical forest facilitates the evaporation and transpiration of water back into the atmosphere to create clouds and consequently more rain, pushing precipitation farther into the forest and across the globe. If we lose large parts of the Amazon to deforestation and agriculture, we lose that pump and the cooling effect that water vapor has on global temperatures. Model-based studies have found that Amazon deforestation leads to less precipitation, as far away as the Pacific Northwest, and reduced snowpack in the Sierra. “Our atmospheric cycles are all connected,” Holm said.

The bad news is that we’re close to losing the Amazon water pump. Prominent environmental scientist Thomas Lovejoy warns, and Chambers agrees, that once 20-25 percent of the Amazon is cleared, we will reach a tipping point in the precipitation regime and witness the permanent transformation of the rainforest landscape into savanna. The World Wildlife Fund estimates that 17 percent of the forest is already gone. If current rates of deforestation continue, we’ll pass that tipping point by 2030.

Most of the world’s soy is used as animal feed to fatten livestock. The destruction of the Amazon reflects the world’s increasing appetite for animal protein.

Unlike in California, large fires in the Amazon are not a naturally occurring phenomenon. Because of their damp climate, tropical forests are not adapted to burn, but farmers in the Amazon have long practiced slash-and-burn agriculture to clear land primarily for cattle grazing but also to grow crops, like soy. In the dry season, August through November, they burn the existing trees and vegetation to prepare the nutrient-poor tropical soil for grazing and planting. These tend to be low-intensity fires at first, but there’s a lag effect–it can take months, even years for trees and vegetation to die, leading to a higher fuel loads and larger and more intense fires than those that blazed before.

While the most recent fire season was not unprecedented, it was bad. According to NASA Earth Observatory, 2019 has seen the highest quantity and intensity of fires in the Amazon since 2010.

So, what explains the uptick? While many point to Brazil’s polarizing new right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro, he’s not the only culprit. Just across the border in Bolivia, the Amazon has been burning at an even higher rate, under left-wing president Evo Morales. The two leaders are on opposite sides of the ideological spectrum but both support policies that encourage deforestation in favor of building up their national economies.

As condemnable as this may seem, Professor Chambers points out that Europe and the U.S., leading critics of Amazon destruction, have long benefited from the exploitation of their own natural resources. If agricultural use of the Amazon is built into the market, why would they expect it to change?

The global narrative that Brazil is singularly responsible for fire in the Amazon not only ignores the fact that nine countries lay claim to some part of the Amazon Basin, it also erases the culpability of global consumers who fuel demand for Amazon-grown commodities like soy, which is largely exported abroad to Europe and China.

Courtesy of Our World in Data // CC

No, it’s not those non-dairy lattes that are driving soy production. Most of the world’s soy is used as animal feed to fatten livestock. In the last 50 years, according to analyses by Our World in Data, global meat production has increased 4-5 fold. Asia and Europe are currently the largest meat producing regions, together contributing nearly two-thirds of the total global meat output. The destruction of the Amazon reflects the world’s increasing appetite for animal protein.

And we can expect more fires and worse burning seasons in the coming years. The most worrying aspect of the recent Amazon fires may be that they are indicative of a much larger pattern. Rising temperatures mean more intense droughts and more intense fire seasons around the globe, from California to Brazil, Siberia to Australia. “We see it in the Amazon, we’re starting to see it here,” Chambers said. “It’s just going to become a more and more dramatic effect. And in terms of where this could ultimately go, we’re only [experiencing] a small fraction of the total expected temperature change.”