The Mideast returned to a high boil last week with the launching of more than a hundred cruise missiles by the U.S., Britain and France against Syrian chemical weapons depots. In the run-up to the strike, President Donald Trump lashed out against Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and Russia, tweeting promises of destruction from above: “Get ready Russia, because they will be coming, nice, and new and ‘smart!’” Trump inveighed. “You shouldn’t be partners with a Gas Killing Animal who kills his people and enjoys it!” As tensions and rhetoric between Trump and Russia continued to escalate, so did public anxiety about the possiblity of war with the superpower.

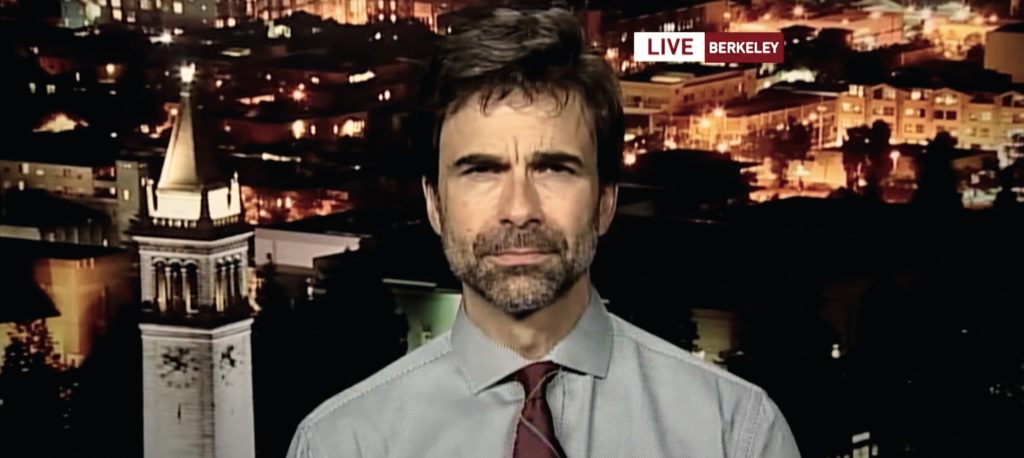

But while the prospect of war with Russia—with its full complement of advanced nuclear weapons and ICBMS—is unnerving, the likelihood of the strike igniting armed conflict with Russia actually is quite slim, says Berkeley School of Information and political science professor Steven Weber. For one thing, as expected, the coalition took exquisite pains to avoid targeting Russian assets. Moreover, the last thing Russia wants is a hot war with the United States, Weber emphasizes. Despite Putin’s saber rattling and boasts of new and exotic armaments, Russia’s military is anemic when compared to that of the United States. Putin is aggressive, certainly, but he’s also eminently sane; he has no intent of pushing the world toward nuclear holocaust. So why he is so deeply engaged in Syria?

“The conventional wisdom is probably right,” Weber says. “During the past five years, Russia has positioned itself as a political spoiler, as a shit disturber, to put it frankly. It is the classic weak player strategy: I’m going to make it harder for you until you give me something I want.”

Weber observes Syria has devolved into a bloody geopolitical chess board that accommodates multiple players: Assad, the various opposition groups arrayed against him, Russia, the U.S., Iraq, Israel, and Iran. Indeed, the major proxy fight isn’t between the U.S. and Russia, says Weber: it’s between the U.S. and Iran.

“Everybody is focusing on Trump yelling and screaming about Obama’s nuclear deal with Iran, but it’s really about a broader and more fundamental view Trump holds,” Weber says. “Obama felt that Iran would do what it’s going to do, and that it didn’t make sense to combine the nuclear stuff with other issues. If we were able to constrain Iran’s nuclear program, that was good in and of itself, and it was unrelated to anything else Iran might be doing.”

Trump, on the other hand, views everything Iran does—including its involvement with Syria and its nuclear ambitions—as a single package.

“He sees the nuclear pact as a gun Iran is holding to our head, allowing them to do other things such as support Assad,” Weber says. “He rejects Obama’s point of view. He wants to deal with Iran as Iran, not approach it in a piecemeal fashion, such as dealing with Iran’s nuclear program, dealing with Iran in Syria, and so forth.”

But back to Russia: Trump’s apparent ire with Russia may be recent, but Putin was never happy with his relationship with the United States, says Weber. Indeed, the current Russian disenchantment extends back to the 1973. Détente between the Soviet Union and the U.S. was just starting to bloom then, and arms reduction negotiations were in progress. The Soviets, says Weber, thought they were participating as equals. The Americans didn’t see it that way. That was brought home during the Yom Kippur War, which started in October and pitted Israel against Egypt and Syria. Israel ultimately encircled Egypt’s Third Army, presenting Russia and the United States with an opportunity for joint mediation: Together, they might’ve negotiated disengagement, given that Egypt was a Russian client state and the U.S. supported Israel. Instead, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger operated independently, pressuring Israel to back off in an effort to pry Egypt away from Russian influence.

“The Russians never really forgave us for that,” says Weber. “They felt that we screwed them over, that they have legitimate interests in the Mideast, that they should be players. The Mideast, after all, is a lot closer to Russia than it is to the U.S. That instilled a real desire for payback. They’re determined that the United States isn’t going to take over that part of the world. That’s why they’re backing the Iranians. Of course, we’re backing the Saudis [Iran’s primary adversary]. Both sides are fighting each other to a standstill [in Syria and Yemen], and the Mideast as a whole continues to get chewed up.”

Weber says that Russia is “doing remarkably well” in executing its weak player strategies, citing the stunning success they’ve had – and are having – with disinformation campaigns in the U.S. and elsewhere. Indeed, echoing concerns from various quarters about the upcoming 2018 U.S. elections, he says we haven’t done enough to counter such mischief.

“While Russia doesn’t want to confront us directly, they do want to weaken us, and it’s clear they intend to keep trying,” says Weber. “I was recently at a meeting with a number of senior government officials and think tankers over this issue, and I came away feeling that the concern is not measuring up to the level of the threat.”

It’s not so much fears that the Russians will launch direct cyberattacks on voting machines, says Weber, “though that is a possibility. It’s more about the disinformation that is ongoing and unrelenting, not just of Facebook but on multiple platforms, and the basic unwillingness to address it. We’re hearing a lot of thoughtful arguments on what to do long term, teaching people how to separate fake news from real news and so on. But what do we do for a threat that is both immediate and existential? What will happen if it gets to the point that we can’t rely on the veracity of election returns? What if that happens this November? Or what if Putin announces tomorrow, ‘Hey, we did elect Donald Trump?’ I don’t want to sound apocalyptic, but the risks to our republic are real.”

A more robust response to Russian provocations is thus warranted, says Weber. That means moving beyond the modest sanctions imposed to date to imperiling the things Putin cares about most deeply.

“Many analysts think Putin is the world’s richest man,” says Weber. “Clearly, he got that way through graft and corruption, and it’s also clear that he would be very displeased if information on his accounts and offshore holdings were released. We know that the Obama administration considered doing that in 2016. It was decided not to go that route, but I think many of the people involved in those decisions wish they had taken a bolder stance.”

The U.S. should also consider launching its own fake news campaigns against Russia, says Weber.

“I don’t know what the U.S. is doing covertly now, but there’s no evidence we’re going after them with the kind of cyberattacks and disinformation they’re using against us,” he says. “Some people will say it’s not the American Way, but we’ve engaged in that kind of activity often enough in the past. And if we don’t at least consider it, we’re playing this game with our hands tied behind our backs.”

Still, maybe the Russians have a point: perhaps they dohave some legitimate interests in the Mideast. And maybe we didn’t really deal with them in good faith back in ’73. So can’t we give it another shot, meet for some cocktails, and reason together?

That’s certainly pretty to think about, and it may even be possible—just not right now, says Weber. He notes that Putin emerged from Russian intelligence, ultimately maturing as “an extremely adroit politician who plays to his strengths when he’s managing subterranean intrigues and relationships. Trump, on the other hand, is not a CIA operative, though he admits to being a ‘very stable genius.’ We missed an opportunity in 1973, and it’s gotten harder ever since. We do have quite a few shared interests, so, yeah, I can imagine we could sit down with them at some point. But we’d need new leadership – on both sides.”