Ever since I was a little kid watching my first conventions in 1952—the veep nominees were Richard Nixon and John Sparkman—I’ve been fascinated by the characters who occupy the number two spot.

I would try to regale anyone who would listen to my tales of such worthies as Levi Morton, Benjamin Harrison’s V.P., who placed the first rivet in the construction of the Statue of Liberty—it was driven right into Lady Liberty’s left big toe. Then I would move on to William Rufus Devane King, Franklin Pierce’s veep, who did literally nothing his entire term: never presided over the Senate, never cast a tie-breaking vote, never even met with the president. Granted, this might have something to do with the fact that he died after 45 days on the job. (Some evidence hints that King also conducted a passionate love affair with President James Buchanan, but that’s another story.)

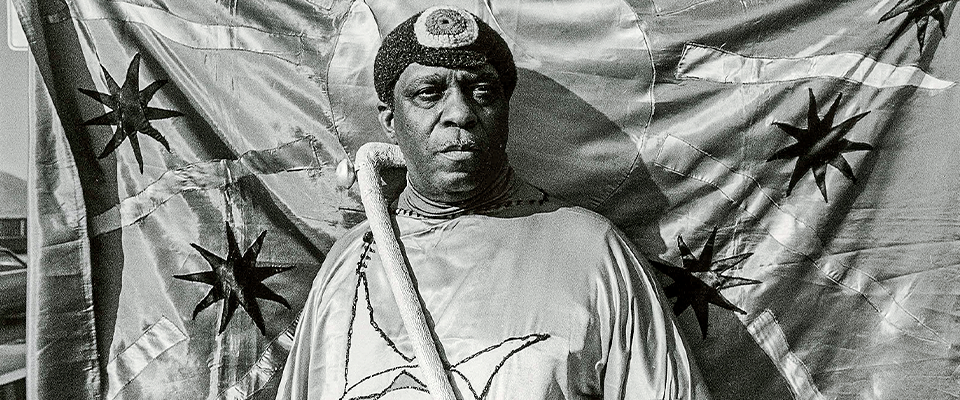

Herbert Hoover’s veep, Charles Curtis, was a direct descendant of chief White Plume of the Kaw Nation and chief Pawhuska of the Osage.

Harry Truman’s veep, Alben Barkley, concluded a stem-winding speech at Washington and Lee University by proclaiming “I would rather be a servant in the House of the Lord than to sit in the seats of the mighty”—and promptly dropped dead at the podium.

In the early days of the republic, the vice presidency was filled by men of distinction such as John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. But it didn’t take long for the office to devolve to obscure nonentities that would eventually inspire the creation of Alexander Throttlebottom, the fumbling, stumbling, bumbling veep in George Gershwin and George S. Kauffman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning musical “Of Thee I Sing.”

“My country,” moaned our first vice president, John Adams, “has in its wisdom contrived for me the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived.”

FDR’s first running mate, John Nance Garner, was even more explicit. For decades, the history books have quoted him as saying the job was “not worth a bucket of warm spit,” but more recent historians think he actually used a stronger word.

When Warren Harding offered the job to Calvin Coolidge in 1920, Coolidge’s wife’s Grace asked him incredulously, “You’re not going to take it, are you?” “I suppose I’ll have to,” Calvin sighed.

As vice president, Coolidge was so obscure that when Major League Baseball sent him free passes, they misspelled his name. And when his house in Washington was evacuated because of a fire, the fire marshal failed to recognize him.

“Once there were two brothers,” Thomas Marshall liked to say. “One ran away to sea, the other was elected vice president, and nothing was ever heard from either of them again.”

Marshall was speaking from personal experience. Given nothing to do by President Woodrow Wilson, Marshall spent most of his time in his U.S. Capitol office, to which he was entitled due to his ceremonial role as president of the Senate. Whenever he left the office door open he could hear the Capitol guides pointing him out to tourists as if he were a curiosity. One day he went to the door and said, “If you look on me as a wild animal, be kind enough to throw peanuts at me.”

But presiding over the Senate (except when the Senate is trying a presidential impeachment, at which point the job goes to the Chief Justice) is a boring, thankless task with no power, as attested to by the fact that in practice it’s given to the most junior senator. On November 22, 1963, the senator in the presiding officer’s chair was 31-year-old Ted Kennedy, who had just been elected to his big brother Jack’s seat, which is why he was the one who had to announce to the senators that his own brother had been assassinated.

Otherwise, the vice president’s work is at the mercy of the president. “I go to funerals. I go to earthquakes,” said Gerald Ford’s veep, Nelson Rockefeller.

But other presidents have given their vice presidents more substantive work, starting with Harry Truman, who was shocked to discover that, as FDR’s vice president, he had never told him about the Manhattan Project. Truman vowed not to do the same thing to his veep, Alben Barkley, which is how Barkley became the first veep allowed to attend cabinet meetings.

Dwight D. Eisenhower increased the power of the vice presidency again when he let his No. 2, Richard Nixon, preside at cabinet meetings three times while the president was recovering from illness. In 1960 a reporter asked Eisenhower if he could think of a major contribution Nixon had made to his administration. “Well,” Ike replied, “if you give me a week I might think of one.”

When Nixon became president eight years later, he was only too happy to use his vice president, Spiro Agnew as Eisenhower had used him. But he never gave Agnew access to the Oval Office. Once, when Nixon’s chief of staff Bob Haldeman told him, “Agnew wants to meet with you,” Nixon replied, “The President doesn’t meet with the Vice President. That’s not how it works.”

Not until the presidency of Jimmy Carter did the vice president, in this case Walter Mondale, merit an office in the West Wing.

“I am the vice president. In this I am nothing, but I may be everything.”

Curiously, almost half of our vice presidents have been older than their presidents, including current Vice President Joe Biden, who is 18 years older than President Barack Obama (the largest age gap in history.) This usually happens when the party thinks an elder statesman on the ticket would calm whatever fears the voters might have about the younger presidential nominee. In 2000 Dick Cheney, who is five years older than George W. Bush, was viewed as a moderating brake on Bush’s perceived impulsiveness (not that it actually worked out that way.)

But the vice president does have one important duty, and it’s a doozy: to assume the presidency if the president dies (as eight have), resigns (as Nixon did in 1974), or is impeached by the House and convicted by the Senate. Marshall summed it up: “The only business of the vice president is to ring the White House bell every morning and inquire about the state of the president’s heath.”

And therein lies the paradox at the heart of the office. “I am the vice president,” said Adams. “In this I am nothing, but I may be everything.”

Lyndon Johnson, as was his wont, put it more crassly. When John F. Kennedy offered him the No. 2 spot in 1960, he had his staff look up the odds for a president dying in office. They turned out to be a little less than 1-in-4. “I’m a gambling man, darlin’,” he told Claire Booth Luce on the night of Kennedy’s inauguration, “and this is the only chance I got.”

Not surprisingly, this can create awkwardness between presidents and their potential successors. “The vice president is like a raven, hovering about the head of the president, reminding him of his mortality,” said LBJ, who was constantly humiliated by the Kennedys, who called him “Uncle Cornpone” behind his back and froze him out of all important decisions.

But when LBJ acceded to the presidency himself after Kennedy’s death, he treated his own vice president, Hubert Humphrey, even worse. “Hubert squats when he pees,” he liked to proclaim, usually in Humphrey’s presence.

However, Johnson’s staffers were right about their actuarial statistics: A president died in office every 20 years from 1840 to 1960—Harrison, elected 1840, Lincoln, elected 1860; Garfield, elected 1880; McKinley, re-elected 1900; Harding, elected 1920; FDR, re-elected 1940; and JFK, elected 1960.

Historians refer to this as either the 20-Year Curse, the Zero-Year Curse (because all these presidents were elected or re-elected in a year ending in zero), or the Curse of Chief Tecumseh, who allegedly pronounced this dire imprecation on Harrison, the first president to die in office, after being defeated by him at the Battle of Tippecanoe.

(Only two quibbles about this theory: Zachary Taylor also died in office, but he wasn’t elected in a zero year. And Tecumseh was never near the Battle of Tippecanoe. The chief Harrison defeated was Tecumseh’s brother, called The Prophet. But why let the facts get in the way of a good story?)

Mathematically speaking, that we’re overdue for another presidential fatality. So the question of whom Clinton and Trump will choose is more than academic.

The streak was broken in 1980, when Ronald Reagan was elected and survived John Hinckley’s assassination attempt the next year, living to finish out his term. It was broken again in 2000, when George W. Bush was elected—or, at least, chosen by the Supreme Court—and finished his term, too.

But this means, mathematically speaking, that we’re overdue for another presidential fatality. So the question of whom Clinton and Trump will choose is more than academic, especially if the winner runs for re-election in 2020.

How did the eight vice presidents who succeeded to the highest office do? The record is mixed. Andrew Johnson, who followed the man many regard as our best president, Abraham Lincoln, is generally viewed as one of our worst, barely escaping removal from office by only one vote in the Senate impeachment trial.

Ditto for Coolidge, whom many historians blame for the laissez-faire economic policies that led to the Great Depression, although those policies were popular at the time. “Nothing was what we wanted done,” said humorist Will Rogers, “and, by God, he done it!”

And Nixon made it to the Oval Office on his own, only to resign in disgrace after Watergate.

On the other hand, Teddy Roosevelt is considered a much better chief executive than his martyred predecessor, William McKinley. Truman wasn’t very highly regarded either when FDR plucked him out of obscurity in 1944—the Republicans sported lapel buttons that said “To err is Truman”—but historians now rank him among the near greats because of the Marshall Plan, the Berlin Airlift, the creation of NATO, and the desegregation of the armed forces. And Lyndon Johnson would be among the greatest of all for pushing through the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act and Medicare, if it weren’t for that damned war in Vietnam.

But the one who really exceeded expectations was Chester Arthur, who succeeded the second president to be assassinated, James A. Garfield.

Arthur was a dandy—a lover of fine clothes, fine wine and fine food—and he was also the poster boy for corruption. The only public office he ever had before being nominated for vice president in 1880 was Collector of the Port of New York. In those days before the income tax, the government derived almost all of its revenue from customs taxes on imports. And since 90 percent of all imported goods came through New York, Arthur’s job put him in the perfect position to skim off as much as he wanted, and he wanted a lot. He became so notorious, President Rutherford B. Hayes made an example of him by firing him from this lucrative post.

The burning issue that split the Republican Party, not surprisingly, was civil service reform, and Arthur and Garfield were on opposite sides. Garfield belonged to the “Half-Breed” faction, who were pro-reform. Arthur, not surprisingly, belonged to the other faction, the Stalwarts, who saw nothing wrong with the spoils system, which had been standard operating procedure in Washington since the days of Andrew Jackson, who proclaimed, “To the victor belong the spoils.”

The Stalwarts were led by Sen. Roscoe Conkling of New York, a handsome man who maintained his trim physique by walking around the Capitol every day with his stomach sucked in. With the “Half-Breed” Garfield as the presidential nominee, Arthur was added to the ticket as a sop to Conkling and the Stalwarts. Six months after they were sworn in, Garfield was shot by a political hanger-on named Charles Guiteau, who exclaimed as he fired, “I am a Stalwart, and Arthur is now President!”

Eleven weeks later, Garfield died, as much due to the ministrations of his doctors as to Guiteau’s bullet. And Arthur entered the White House under The Mother Of All Clouds.

Everybody—the Half-Breeds with fear, the Stalwarts with glee—expected he would do exactly what Conkling told him. Instead, he turned his back on his old mentor and lobbied for, signed, and strongly enforced the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, one of the shining exceptions to the otherwise sordid Gilded Age. The Stalwarts were furious, but Arthur didn’t care. He knew he was a dying man. He retired at the end of his term and lived only a few months after. Former President Hayes attended the funeral. Sen. Conkling did not.

“No man ever entered the Presidency so profoundly and widely distrusted as Chester Alan Arthur,” wrote a contemporary journalist, “and no one ever retired more generally respected alike by political friend and foe.”

When I was a kid watching those conventions in 1952, it was a commonly held belief that the office makes the man and not the other way around. In one case, at least, it was true.

One in a series of personal Perspectives. We invite writers and readers to submit their own essays—inspiration can come from California magazine or California Magazine Online stories, the news, or issues of the day. Read more.