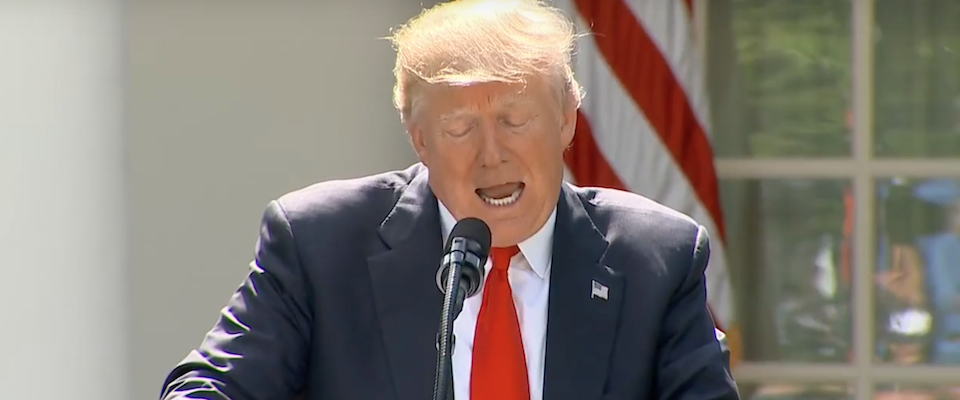

The bunker metaphor may be overdone in regard to the White House and its current occupant, but that’s not to say it isn’t apt. Trump is taking a massive amount of incoming, and it’s having a profound effect on him personally and administratively. Recent staff leaks describe him as “agitated and exhausted” and much, though not all, of his agenda has stalled.

But which of the many arrows of outraged misfortune heading his way could stick? Which have the velocity and mass sufficient to result in impeachment or resignation? Collusion with Russia? Violations of the emoluments clause of the Constitution? Obstruction of justice? All or none? Democrats are giddy at the prospect of a hamstrung Trump, with many predicting, on Facebook, at least, that impeachment is just around the corner. The UC Berkeley experts interviewed for this piece were more skeptical.

Both the political and business realms are littered with the figurative corpses of Trump’s adversaries, but no matter how bad things look for the President, it’s by no means certain he’ll succumb from his latest travails. Ultimately, his fortunes are tied not so much to what he did or didn’t do, but by his relationship with Congress.

Take emoluments, for example. This constitutional clause forbids anyone holding an “Office of Profit or Trust” in the US government from accepting money, gifts or jobs from a foreign state, unless specifically authorized by Congress. Trump, say many analysts, has violated this provision in a variety of ways, ranging from recent trademarks granted by China for Trump enterprises to profiting from foreign dignitaries lodging at Trump hotels. Indeed, the attorneys general for the District of Columbia and Maryland filed a lawsuit earlier this month claiming Trump breached the emoluments clause by renting rooms in his hotels to government representatives from Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Kuwait, and Georgia.

But applying the emoluments provision to such transactions, says UC Berkeley Law professor emeritus Robert Cole, “…is a stretch, particularly where dignitaries staying at his hotels are concerned. For me, the trademarks issue is potentially a far more serious conflict of interest.”

The House of Representatives could consider either case grounds for impeachment, says Cole, but likely won’t. That’s because impeachment ultimately is a political process, not a legal one. The standards for impeachment are determined by House members on an essentially ad hoc basis; if Representatives consider the grounds sufficient, then they’re sufficient, whether or not they correspond to specific legal violations. And after impeachment, essentially, an indictment of the Chief Executive, the US Senate has the same leeway in determining whether or not it will remove the President from office.

“The only thing I see so far that could tip the scale would be if substantial evidence emerged showing he knew the Russians were working to influence the election in his favor.”

“Given the Republican majorities in both the House and Senate, I frankly don’t see that happening anytime soon,” says Cole.

Jesse Choper, a Berkeley Law professor emeritus and constitutional law expert, thinks the emoluments clause is too vague to force Trump out of office under current circumstances.

“In fact, the only thing I see so far that could tip the scale would be if substantial evidence emerged showing he knew the Russians were working to influence the election in his favor,” says Choper. “That could either force him to resign or convince the House to impeach and the Senate to convict. Other than that—it just seems unlikely to me.”

Jack Citrin, a Cal political science professor and the director of the university’s Institute of Governmental Studies, also thinks it’s “far-fetched” that the current accusations and insinuations bedeviling Trump could result in his removal from office.

“Collusion with the Russians could do it,” says Citrin, “but it probably wouldn’t be enough if it’s only demonstrated that subordinates like [former National Security Adviser] Michael Flynn were involved. It’d probably have to somehow pertain [directly] to Trump.”

The one thing that could get federal legislators off the dime and start thinking seriously of impeachment and conviction, continues Citrin, is any significant change in Trump’s standing among his base of hard core devotees. If his support erodes significantly, Citrin observes, Republican Representatives and Senators, worried about their own fortunes in 2018 and 2020, would likely abandon him.

“Right now, Republicans are wringing their hands,” Citrin says. “Given the control they exert [post election], they anticipated a complete reshaping of government. But due to Trump’s ineptitude, they’re finding it impossible to advance their agenda. And now they’re also worried about the upcoming midterm elections—and they should be. The few grown-ups in the administration such as [Secretary of State Rex] Tillerson, [Secretary of Defense James] Mattis, and [National Security Adviser] H.R. McMaster are doing what they can to promote a rational foreign policy, but they still find themselves undercut by the president.”

Still, the chaos surrounding the administration has allowed some components of the Republican agenda to slip through without much resistance, or even attention, says Charles Weisselberg, a professor at Berkeley Law and an authority on criminal law.

“Russia has sucked all the oxygen out of the room, and certain priorities such as environmental deregulation and changes in civil litigation group claims and class actions have progressed,” says Weisselberg. “Has that been intentional on Trump’s part? I don’t know. But he certainly can’t stop tweeting about them.”

There is, of course, a wild card in this farrago: Special Counsel Robert Mueller. If, in the course of his investigations, Mueller finds hard evidence that inculpates Trump, then the President could very well face impeachment. Many of Trump’s critics opine that a criminal indictment would be more appropriate than mere impeachment, but again, that may be overreaching, at least while Trump remains in office.

“There has been considerable debate about whether a sitting president can be charged with criminal offenses,” says Weisselberg. “Many argue the Constitution implicitly provides impeachment as the sole process for removing a serving president. However, a president who resigns or is removed from office can then be criminally prosecuted.”

Trump has hinted that he may scotch any threat from Mueller by dealing with him as he did with former FBI director James Comey. But firing Mueller would result in so much blow-back that it could motivate Republican legislators to abandon Trump and move toward impeachment. Moreover, says Weisselberg, Trump would likely find it technically difficult to 86 Mueller.

“Under current regulations, the only person who can fire the Special Counsel is the person who appointed him, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, or his replacement if he resigns or is removed,” says Weisselberg. “And even if Trump ordered Rosenstein to fire Mueller, Rosenstein would have to demonstrate good cause for removal, such as incompetence or malfeasance. If Mueller were fired without demonstrating such cause, it would certainly create a stronger appearance of obstruction of justice.”

But even if Mueller’s investigations proceed unimpeded, Trump opponents shouldn’t necessarily expect to learn who knew what when, or who did what to whom. When Mueller has completed his investigations, says Weisselberg, he will provide the Attorney General with a confidential report. The Attorney General, in turn, will notify the leaders of the House and Senate Judiciary Committees of the findings.

Despite Trump’s deep unpopularity, Republicans have taken all four recent special congressional elections, including this week’s much ballyhooed race for the sixth congressional district in Georgia.

“The regulations provide that the Attorney General may determine that a report should be released publicly,” says Weisselberg, “but they don’t require that.”

In any event, the conclusion of Mueller’s investigation is many months or even years away, and it is almost certain that Trump will not face impeachment any time in the foreseeable future, or perhaps, ever. As the experts aver, impeachment is a political, not a legal process, and the current House of Representatives will remain deeply resistant to the move unless incontrovertible evidence is produced confirming the president is guilty of the “…treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors…” stipulated in the Constitution. (And as Cole notes, “misdemeanor” in this context doesn’t mean the minor criminal offenses usually associated with the term; it suggests misdeeds that may not technically qualify as high crimes, but are nevertheless serious.)

So in blunt terms, it’s likely that a Democratic House of Representatives is a prerequisite for impeaching Trump, meaning everything could come down to the 2018 midterm elections. Indeed, “impeachment congress” is gaining traction as a trope. But so far, Democrats haven’t exactly covered themselves with glory in their attempts to rebuild their party following the 2016 election rout. Despite Trump’s deep unpopularity, Republicans have taken all four recent special congressional elections, including this week’s much ballyhooed race for the sixth congressional district in Georgia.

So instead of magical thinking—imminent impeachment, for example—Democrats might be best advised to undertake the long, slow, arduous task of finding candidates that speak the language of average people, then getting them elected at the grassroots level on up, from school boards to state legislatures, and finally, to national offices. They need to crib from the Republicans’ playbook, in other words.

“Even if Trump is impeached and removed from office, you end up with President Pence,” says Cole, “and most Democrats would probably not consider that an improvement. Pence certainly is less erratic than Trump, but he’s more conservative socially, and no one really knows what he thinks on foreign policy. The Democrats should be concentrating on 2018, identifying the districts where they have a chance, and developing a positive program that engages voters. Simply being against Trump isn’t enough.”