Women are much more likely to be lied to than men during a business transaction, says a new UC Berkeley study.

And we’re not talking about the clichéd stories of the car salesman selling the “little lady” the lemon on the lot or the oil-change guy talking a female customer into buying a new fan belt for her car, whether she needs one or not. Negotiators are more apt to try to hoodwink even a high-powered business woman than they would her male counterpart, according to the research. In a study of some 300 students pursuing masters’ degrees from the Haas School of Business, 24 percent lied to female negotiators during the course of role playing to close a deal. Only 4 percent lied to men.

The reason, says Laura Kray, the lead researcher and a Haas professor, is simple: Women exude less confidence in negotiations and are therefore perceived as less competent.

“Once you’re perceived as incompetent, people think you’re easier to mislead,” says Kray, adding that even women see their own gender as marks.

Although men were more likely to be deceitful to women, 15 percent of the study’s female subjects tried to dupe their female opponents during a make-believe real estate transaction. And almost always, men were perceived as better negotiators—more confident, competent and harder to mislead.

The study, which explores behavioral negotiations and appears in the academic journal Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, comes in the wake of a provocative piece in The Atlantic. In that article, writers Katty Kay and Claire Shipman, authors of the 2009 book “Womenomics,” blame “women’s acute lack of confidence” for holding back females in corporate America. And Berkeley’s research seems to bolster that theory.

No doubt, cultural and institutional mores, not to mention motherhood, have contributed to women’s stagnation in the workplace—the Sheryl Sandbergs and Marissa Mayers of the world are anomalies. The lack of women executives is staggering.

Of Fortune 1000 companies in the United States, less than 5 percent of the CEOs are women, 8 percent top earners, 15 percent executive officers, and less than 17 percent hold board seats, according to a 2014 report by Catalyst, a nonprofit dedicated to advancing women. The organization also found that a woman on average earns $4,600 less a year than a man holding the same entry-level position. By the time a high-tier professional woman is mid-career, she’s making $31,000 less than her male colleagues, according to Catalyst.

“There is an inherent bias against women,” says Anna Beninger, director of research for Catalyst. “If women business leaders act consistent with gender stereotypes, they are considered too soft. If they go against gender stereotypes, they are considered too tough.”

Yet the latest Berkeley research suggests that no matter what attitude women take, it might not even make a difference—as far as some men and even women are concerned, the mere fact of being female dooms from the get-go to be undervalued. Although the Berkeley researchers presumed that a “soft” woman was more likely to be misled during a business transaction than a “tough” woman, it turned out not to be true. Having “warmth” or positive intentions toward others (otherwise known as being a nice person) wasn’t a liability in negotiations, the study found. The liability was simply being viewed as less capable.

While conducting a transaction with a person perceived to be incompetent—most often a woman—the negotiators in the role-playing exercises were more willing to relax their ethical standards and go in for the kill, according to the study.

“They just out and out lied,” Kray says. “They recognized that they would be exposed during the course of the study, and they lied anyway.”

She believes that women, at least the business graduates in the study, are viewed as less competent because they doubt their own ability to negotiate successfully. “In the beginning of the program, I survey all the students,” she says. “Women overwhelmingly report lower confidence levels in their negotiating skills. Negotiating is seen as a masculine domain and women are aware of this. If they’re demanding they’re seen as ‘ball busters.’ Instead, they want to be fair minded, where the men don’t care. The whole thing becomes a negative experience, leaving the woman asking, ‘Why did I ever go to business school?’ ”

And that can breed even more insecurity, which can turn into a self-fulfilling prophesy of failure. Especially because studies show that confidence is the key to success—even if it turns out that the person is actually inept.

Cameron Anderson, a professor at the Haas School of Business who has done much research in the area, has found that people who think they are more talented than their colleagues get ahead, whether they deserve to or not. Not the blowhards or the know-it alls—they’re just obnoxious, Anderson says, although a fair amount of them get ahead, too.

But he is referring to “people who display an absolute belief in themselves.” It may be subtle, but it’s there, bubbling under the surface.

“In their heart of hearts they believe they can get the job done,” he says, adding that in reality they’re typically not as competent as they think.

During his 12 studies—he began in 2008, looking at 1,000 undergraduates and graduates—participants who credited themselves with having outstanding knowledge of various topics turned out to have merely a mediocre understanding. For example, in one situation students were asked to locate 15 U.S. cities on a blank map and then to rate their performance, many thought they had nailed it, when in reality they’d only performed about average. (They were never told how they actually did). Still, the overconfident students were shown more respect and perceived to be more proficient by the group than those who had more accurate self-perceptions, according to surveys in which Anderson asked participants to rate their fellow students’ competence levels.

So is overconfidence all it takes?

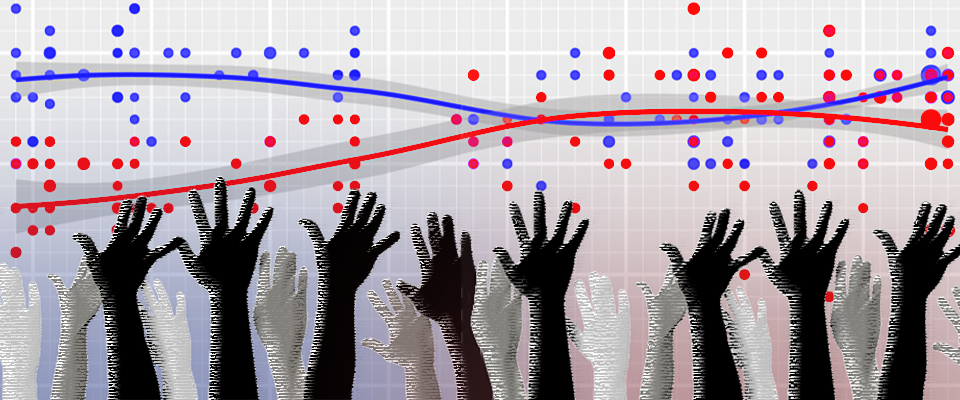

Not necessarily. If you look at younger women, specifically millennials entering the workplace, there is evidence to suggest that they should have confidence in spades. They’re better educated, surpassing men in both college enrollment and completion, according to the Pew Research Center. And they make up half of the work force. In 2011, 66 percent of women ages 18 to 34 ranked being successful in a high-paying career as a top priority as opposed to 59 percent of men, according to a Pew poll. That percentage for women increased by 10 points from 1997 (and by only 1 percentage point for men), signaling that females may feel more empowered. Or conversely, they may feel more desperate to overcome the factors working against them.

Regardless, the polling clearly indicates that, for whatever reason, millennial women are more driven. Even so, they are not starry-eyed. Every day they see evidence of a gender gap in their workplace. For some, like Danielle Lerer, it’s subtle, but has an impact nonetheless. Three years ago, Lerer left UC Berkeley with a master’s degree in public health, got a job at Kaiser Permanente and has thrived—she recently was promoted to just one step below management. But despite her department being evenly split gender-wise, all of her bosses are men. Lerer says the disparity can take a toll.

“It’s nothing so obvious,” she says. “But I think the women are less confident as a result. There’s a slight difference in talk time—men do more talking at the meetings and there have been instances of men talking over the women.”

Catalyst’s Beninger says perhaps this is the essence of the confidence gap. “The myth is that women are to blame for not advancing,” she says. “But the blame should be placed on the organization for not doing better.”

If people of both genders are likelier to underestimate women’s competence, and more likely to try to take advantage of them, it’s only natural for women to question their own abilities. And if men are always at the top of the pyramid, it’s only logical for women to anticipate smacking into that glass ceiling.

The stark paradox for many women: their odds of success undercut their confidence, and low confidence undercuts their odds of success.