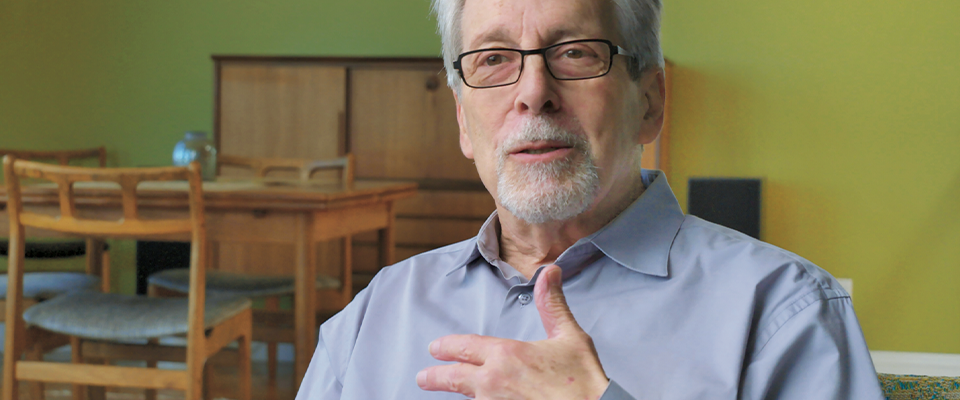

Each year, UC Berkeley linguist Geoffrey Nunberg chooses a Word of the Year: A word, in other words, that was in particularly wide usage and seems to sum up the zeitgeist. Nunberg had a few good contenders for 2015, including “refugee” (due to the crises in the Middle East and Europe and along the Rio Grande) and “microaggression,” the practice of employing subtle snubs to denigrate or intimidate. (Microaggression became a particularly hot topic in educational circles over the past year, generating everything from a UC policy to a series of South Park episodes.)

But Nunberg settled on “gig”—no, not the horse-drawn carriage, the light rowboat, or the trident-like spear that Southern good ole boys use to impale frogs. “Gig” in this context refers to the one-off assignment, the temporary work contract, the employment mode that is fast replacing the full-time, benefit-blessed job model that now seems as quaint as pearl-buttoned spats and swagger sticks.

The term has been employed for more than a century to describe musicians’ engagements, usually of the one night bandstand variety—although etymologists and jazz fans are split over whether the origin of the word dates back to the French “gigue” for a lively dance, or to the one-horse carts that musicians such as Louis Armstrong played out of in New Orleans to evade getting hassled for playing on the street. Soon the word crept into use in other fields; Jack Kerouac used it in reference to his employment as a part-time brakeman for the Southern Pacific Railroad, and by the late 1960s it was a standard component of hippie parlance.

“‘Gig’ was a natural for the hippies who succeeded the [Beat era] hipsters, who made the avoidance of regular work a condition of tribal membership,” Nunberg wrote in a commentary published in the Los Angeles Times. “But the word’s more subversive overtones receded along with the counterculture. In recent decades, ‘gig’ has become a hip term for any temporary job or stint, with the implication that you’re not particularly invested in it. I think of the barista or bookstore clerk, who responds to my questions with a look that says, ‘Hey, man, it’s a gig. I don’t really DO this…’ ”

But Nunberg implies that many such giggers may be in deep denial; that in fact, it IS what they do. The gig economy, he writes, is “the predominant name for what’s being touted as the industrial revolution of our times. The lifetime job is history, we’re told, a victim of technology and the market. Instead, careers will be a patchwork of temporary projects and assignments, with the help of apps and platforms with perky names like FancyHands, Upwork and TaskRabbit….”

Indeed, the trend has been heralded by many as a boon, a liberation from the dreary cube farms that exemplify full-time white-collar employment. “Today, careers consist of piecing together various types of work, juggling clients, learning to be marketing and accounting experts, and creating offices in bedrooms/coffee shops/coworking spaces,” writer Sara Horowitz gushed in The Atlantic. “Independent workers abound. We call them freelancers, contractors, sole proprietors, consultants, temps, and the self-employed. And, perhaps most surprisingly, many of them love it. The transition is nothing less than a revolution….”

“The buzzwords fly thick and fast here…. But that language doesn’t get at most of the people who are cut loose in the new economy and who aren’t reveling in the independence it gives them.”

Well–maybe, and to a certain degree. Gigging is one thing if you’re young, unattached and restless. It’s liable to be quite another if you’re older, burdened with family responsibilities, recently downsized, and you’ve discovered that full-time jobs with decent salaries and benefits are almost as scarce as Powerball winners. At that point, gigging can feel like a necessary evil more than a welcome revolution. You’re apt to awaken every morning with the thought “Where’s my money?” lodged in your forebrain. The much-vaunted freedom promised by the gig economy can ultimately translate as the freedom to work ten hours a day, seven days a week. And that’s if you’re lucky and can find gigs.

“The buzzwords fly thick and fast here,” Nunberg observes. “We’ll be solopreneurs, free range humans with portfolio careers…. That’s the image that phrases like ‘the gig economy’ and ‘freelance nation’ bring to mind, an economy populated by professionals and creatives, typically single millennials…. But that language doesn’t get at most of the people who are cut loose in the new economy and who aren’t reveling in the independence it gives them—the ill-paid temps and contingent workers that some have called the ‘precariat.’”

Reflecting the appositeness of Nunberg’s Word of the Year choice, gigging’s dark side increasingly is a favored topic for economic analysts and social commentators. Writing for the Huffington Post, McKinsey Global Institute partner Susan Lund observes that the trend is “creating flexible opportunities for individuals who want to be free agents, but raising real concerns about the insecurity associated with the so-called gig economy … many of the jobs created by contingent work platforms do not add up to a living wage.”

Predictably, a Mother Jones article offered a more pungent evaluation. In a piece titled “The ‘Gig Economy’ Is Mostly Silicon Valley Hype,” Kevin Drum labeled the upside of the trend as “a figment of the Internet’s imagination,” noting job growth in the sector was mostly flat through 2015. “Maybe the gig economy will be a big thing in the future,” he wrote. “Maybe. For now, though, it appears to be mostly just another example of the reality distortion field that Silicon Valley is so good at.”

Given that it’s his job to have a way with words, perhaps it’s no surprise that Nunberg sums it up best:

“When you hear ‘freelancer’ you don’t think of the people cobbling together a livelihood cleaning apartments, delivering groceries and doing other people’s laundry,” he writes. “And not many of those people think of themselves as having gigs. Unless you’re a bass player, calling a job a gig is a luxury reserved for people who can pretend they don’t need one.”