Like D.H. Burnham’s design of a century ago, Lisa Iwamoto’s rendering of a future San Francisco reveals the anxieties of the age.

Near the end of his comprehensive 1905 development plan for the city of San Francisco, internationally renowned architect D.H. Burnham considered the question of water. The obstacles weren’t what your drought-stricken 21st-century San Franciscan might imagine. The water would come from the Sierra and, Burnham wrote, “As it will be limitless, the reservoirs should be vast and designed to be in themselves a feature of the city.”

Most of all, he did not want the reservoirs to interfere with his vision of a gigantic neoclassical Athenæum at the base of Twin Peaks. Living through a great economic boom and expansion before the Great Earthquake, San Franciscans apparently wanted to establish their city as an international center for Greco-Roman sculpture and intellectual pretension.

Little that Burnham proposed was built. He’s a great reminder, though, that asking architects to imagine a city a century into the future is basically asking for pulse-of-the-city-style psychoanalysis: What are people anxious about? What are their hopes, dreams, desires for their city?

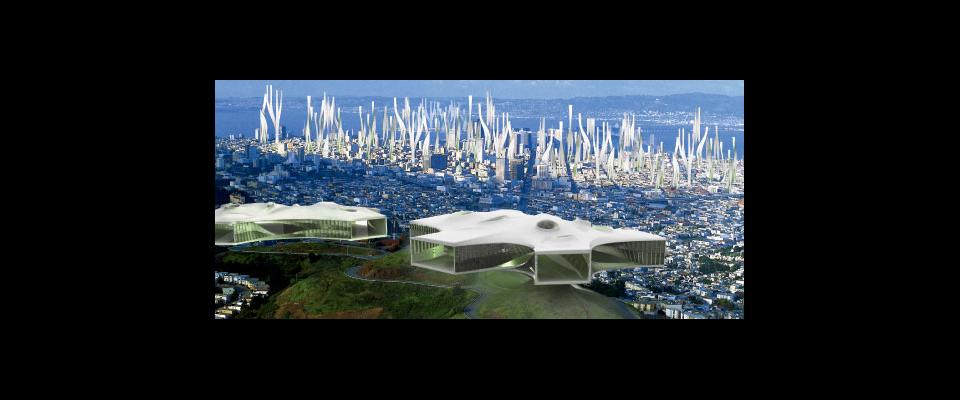

Which brings us to 2008, and the History Channel’s “City of the Future” competition asking architects from Atlanta, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C., to imagine their cities in 2108. The regional finalist from San Francisco was HydroNet, the vision of San Francisco submitted by Berkeley Professor Lisa Iwamoto and her firm, IwamotoScott Architecture. They lost, in the national online vote, to Atlanta. But there is a psychological lesson to be learned from Iwamoto’s design. The brave citizens of San Francisco are currently scared senseless about the world’s environmental state. The HydroNet project offers an inspiring creative vision to combat environmental despair.

Almost every feature of the IwamotoScott design is aimed at sustainability. The project proposes an “occupiable infrastructure” that combines housing and transportation with a network for power, water, and food distribution. Giant “fog flowers” catch fog for water, bayfront algae farms produce biofuels for hydrogen-powered cars, “geothermal mushrooms” generate energy, and permeable pavement recharges the city’s huge underground aquifer.

There is no suggestion of a need for more neoclassical architecture. The new housing structures imagined by IwamotoScott look like giant waving tentacles poking out of the bayfront Embarcadero.

Iwamoto says she wants people to imagine things they wouldn’t normally think about, but decide, “It’s kind of cool … and something more than a square box on a hill.” Peering into the future often makes architects look silly, but “you have to take a leap of faith,” Iwamoto says. As Burnham attempted to address cultural insecurities, his modern counterparts face the prospect of designing a waterfront city where sea level is projected to rise by as much as five meters. “We’re facing a global climate crisis,” Iwamoto says. “That was just too big to [not address].”

But as catastrophic as it now seems, climate change might not be the overriding concern of architects 100 years in the future. And regardless of whether the San Francisco of 2108 features giant, live-in waterfront tendrils, the HydroNet project will stand as a record that in 2008 architects were thinking of ways to give their future colleagues the luxury of worrying about something else. As Burnham wrote a century ago, “While prudence holds up a warning figure, we must not forget what San Francisco has become in fifty years and what it is still further destined to become.”