To the Chinese, freedom of speech isn’t really the issue.

They have closed off Tiananmen Square.

The huge portrait of Mao stares across an empty Square at the giant mausoleum to the south where the Chairman’s body is usually on display. Officially the Square has been blocked off because the President of Malaysia is visiting. But today is June 3, the anniversary of the 1989 uprising that left hundreds dead in Beijing—perhaps more, nobody really knows—and jolted all of China. Police are everywhere. The Square is ringed with soldiers.

And the government has laid down the line: “The safety and security of Tiananmen Square and other key areas is the first and most important priority—they must be rigidly controlled and kept absolutely secure. We must appropriate our successful experiences during the Olympic Games …. We must adequately guide public opinion and be mentally persuasive, creating a healthy and harmonious public opinion environment.”

This means you must not talk about what actually happened in 1989.

Twenty years earlier, weeks of escalating student protests and a massive hunger strike in the Square had spread dissent to many parts of the country. The government was split and vacillating. Finally Deng Xiaoping, the man who had brought capitalism back to China, asserted control. Military units were sent into Beijing with orders to suppress the students by any means necessary, and on June 4 they reached the Square. Faced with tanks and machine guns, the students were persuaded to abandon their hunger strike and leave. There were no deaths in Tiananmen Square itself, but many supporters died on the Square’s western approaches.

Today, television and the print media are controlled and “Tiananmen Square Massacre,” “June 4,” and “Chinese democracy movement” are all censored terms on the Chinese Internet. The government has shut down many local websites. “We have designated June 3 to June 6 as the national server maintenance days,” it piously explains, “This move is widely supported by the public.” Meanwhile, foreign sites including Facebook, Twitter, and Flickr have been blocked. Public discussion of what happened in 1989 is off limits, pushed behind the Great Firewall.

For a Westerner studying Mandarin at language school, the tight governmental control is a weird experience. And can it work in a country with 300 million Internet users? Three Beijing experts offered some surprising opinions.

Jeremy Goldkorn, a fast-talking South African, edits Danwei, the best known English-language website in Beijing. “People see this country as an unreconstructed totalitarian state,” he tells me. “Western media tend to give people the impression it’s still the 1970s here, which it’s certainly not. There is debate in China. There are people willing to give the authorities the middle finger. If you’re trying to understand China, if you think that everybody is a robot, you’re not going to understand what’s happening here.”

We are sitting in the Stone Boat café in Ritan Park, one of the beautifully tended parks that make Beijing bearable in midsummer. Around us, mixed groups of Chinese and Westerners from the city’s new business class sip white wine and Tsingtao beer.

The Internet has become a Fourth Estate in China, Goldkorn says. “Kids know how to use free proxy servers. There are people who download Freegate and Ultrasurf, these Falun Gong tools that help you get around the firewall. This Green Dam thing has been discussed and compared ….”

Green Dam is the filtering software that the government wanted installed on all new PCs—supposedly to filter out pornography, though it would work just as well on politics. Under a hail of withering comment on the Web, the government backed off. “Green Dam Girl,” the anime figure created to protest the software, has become an Internet meme representing governmental stupidity.

“Westerners tend to underestimate the incompetence of the Communist Party when it comes to good old-fashioned totalitarianism,” Goldkorn said. “That said, they’ve done a really great job economically …. Few people here are interested in sacrificing practical gain for principles …. Free speech is way back there. It’s not a priority of pretty much anyone.”

“I myself have got to the point where I’m not paranoid any more,” he said. “You can have a very free intellectual life here thanks to the Internet. You can sit here in Ritan Park and say ‘Zhao Ziyang’ and nobody’s going to stop you.”

“Zhao Ziyang!” he shouted out to Ritan Park. “Zhao Ziyang!” He was talking about the General Secretary of the Communist Party and former premier who went out into the Square in 1989 to talk the students out of the hunger strike.

For this Zhao was put under house arrest for the remainder of his life, which turned out to be 16 years. His posthumous memoirs, smuggled out of China, were published in the West last year, to coincide with the anniversary. He is an unperson in China, his name a banned search term on the Web.

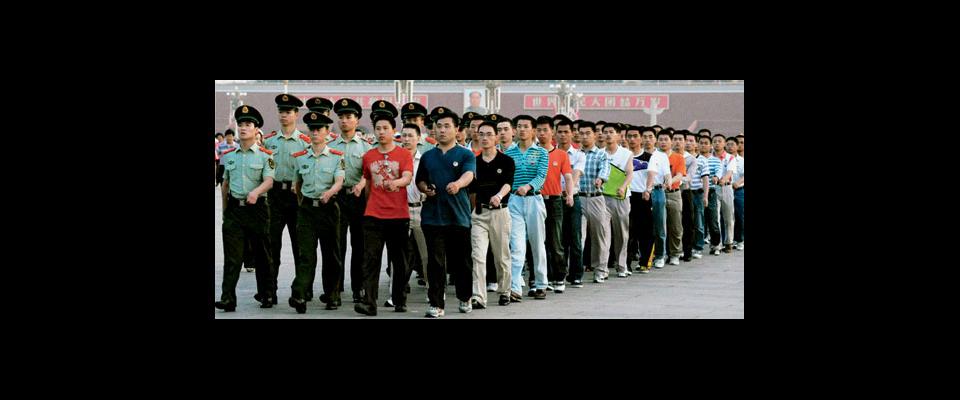

The Square is open the next day. There are plain-clothes police on the approaches and uniformed police are carefully checking IDs. But in the Square, things appear normal, at first. Chinese tourists are snapping pictures of each other as usual. But every part of the Square is also occupied by a group of sturdy young men in matching-colored shirts—red shirts in front of Mao’s portrait, orange in front of the Great Hall of the People, yellow in front of Mao’s Mausoleum. They are volunteers or police auxiliaries. The cheerfulness is a lie: Any kind of demonstration will instantly be squelched. Nobody comments on this. Nobody attempts to talk to the colored shirts. After 20 years of the “healthy and harmonious public opinion environment,” have they simply forgotten what happened here 20 years before?

“I’ve lived here long enough to develop some empathy for the regime,” says Kaiser Kuo ’88, a musician, writer, and successful media consultant, known as the man who introduced heavy metal music into China. “I don’t buy that if they liberalize a bit, suddenly all hell breaks loose and the country spins wildly out of control. But they really do believe that. They look at Teheran and they think that could happen here.”

Kuo was touring China in June of 1989 with his band, Tang Dynasty (named, he says, for the openness to foreign influences of the Tang era, AD 618–907). Then the country blew up. Kuo left hurriedly and spent the next few years trying to understand what he had seen. In 1995 he came back to China and he’s been here ever since.

Kuo, a slightly intimidating figure with an emphatic style, is not romantic about 1989. “The students didn’t realize what they were doing,” he says. “They were playing with symbols that gave them far more political potency than they were ready to manage. The students didn’t think through the consequences of their extremism.”

We are meeting at Starbucks in the WanDa shopping center—one of the many glittering new malls in consumption-crazy Beijing. Terminator IV and Night at the Museum II are playing next door, and well-dressed young people are text-messaging all around us. The Internet, Kuo thinks, has heightened the political tension because so many people now have access to information. “How many people had devices in their hand in 1989? These issues are now being talked about in the mobile phone world. There’s a whole lot more water behind that dam ….”

“Everyone wants civil rights. It’s just a matter of getting from A to B.”

Even the government? I ask.

“I think the government eventually does want it. These are incredibly pragmatic people. They are not sinister and malign. I think they are trying to create conditions that lead to genuinely more democratic policies. But … ‘feed them, clothe them, and house them’ first.”

Starbucks closes, decanting us into the sweaty Beijing night. “Why is it,” Kuo says, “that the only people who get uptight about it are foreigners? There’s a fundamental question that plagues Americans: Why don’t the Chinese hate their government as much as I think they ought to?”

I walk back to my apartment mulling over this reproof and turn on the TV. The Teheran demonstrations are running on CNN—emailed cell-phone videos of frantically running crowds and baton-swinging riot policemen “… very reminiscent of the Tiananmen demonstrations of 1989,” the commentator says.

Instantly a censor somewhere pushes a thumb down on a button and CNN goes black.

Maybe it is only dumb foreigners who get uptight about 1989. Only dumb foreigners from the older generation, at that: The expat students at the language school aren’t interested. I am relieved when my 24-year-old Chinese teacher pulls out a single memory. “My father said the tanks were parked behind the Great Hall of the People,” she says. “Where the National Theater is now.” Single memories are all you have when collective memory is erased.

Liu Xiaobiao, a journalist and editorial writer based in Beijing (and a Visiting Scholar at the Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism in 2004) was at the Square in 1989. He is another no-nonsense Chinese intellectual with an intense and powerful rhetorical style. We met at my apartment, in an affluent development near an upscale mall with a Fauchon grocery in the basement.

“The censorship towards the media is stricter, more intensive now than before,” he says. “However the result is getting weaker and weaker. This is because there are so many problems in China. If you don’t want us to cover one story, we can cover another story. They cannot censor everything.”

And, he adds, there are many outlets. “So if you don’t allow me to publish an article with a certain opinion, I will find another way to express my opinion.”

But Liu is wary of the politics of the Internet. Its “civic agenda,” promoting justice and opposing corruption, is weak, he says. “We have to take a close look at Chinese Internet users … 70–80 percent of them didn’t receive a college education.” This, combined with the rise of nationalism, means the online “commercial agenda” is much more potent than the civic agenda. “Most of the Internet users only care about sex or the NBA.”

And what about the government’s heavy censorship of the June 4 anniversary?

“Hai pa!” he says sharply. I know what that means: “They’re scared!”

“In 1989 I was a college student and I participated in the events in Tiananmen Square,” he says. Afterwards, he says, he believed the government would “tell the truth sooner or later.”

Then he tells a story about Peking University in northwest Beijing, which produces the country’s elite and was a wellspring of the 1989 protests.

In the former political center of the campus he found no students, only what appeared to be plainclothes policemen. And on the walls where the political posters were in 1989, “there were only advertisements. I saw some students having class, so I just entered and listened. The teacher was young, younger than me. That class was about politics.”

They were discussing the Anti-Rightist Movement of 1957, which punished intellectuals who dared to criticize the Communist Party during Mao’s brief Hundred Flowers campaign. Some 300,000 lost their jobs or went to labor camps. It was a forerunner of the brutal attacks of the Cultural Revolution. “The teacher put out some posters about the Anti-Rightist movement and the students laughed when they saw them. The general meaning was that the Anti-Rightist movement was necessary because those people started to attack our socialism and our government.

“So at that moment I felt that not only the students had changed but also the professors had changed. After 1989 the government education control in the university was very effective and they achieved their goal.”

The last word goes to Sima Qian, the Han Dynasty historian (ca. 100 BC). This comes from the Web (of course), via Jottings from the Granite Studio, the blog of Jeremiah Jenne, a Beijing-based Qing historian from UC Davis whom I met for breakfast in the embassy.

[King Li of Zhou] acted cruelly and extravagantly. The people in the capital spoke of the king’s faults. The Duke of Shao remonstrated, saying: “Your people can no longer bear your orders.” The king was angered. He found a shaman from Wei and had him watch for criticism. Whomever he reported was killed. The criticism subsided, [but] the feudal lords stopped coming to court. In the thirty-fourth year [of his reign], the king became even more stern. No one in the capital dared to say a word, but only glanced at each other on the roads. King Li was pleased. He told the Duke of Shao: “I was able to stop the criticism. Now they dare not speak.”

The Duke of Shao said: “This is [merely] stopping up criticism. To block people’s mouths is worse than blocking a river. When an obstructed river bursts its banks, it will surely hurt a great number of people. People are like this, too. For this reason, those who regulate rivers dredge them and let them flow; those who regulate people broaden [channels] and let them talk ….

The king would not listen. Then no one in the capital dared to say a word. Three years [later], they joined each other in rebellion, and attacked the king. King Li fled to Chih.

At the end of our interview, Jenne warns me that there might be difficulty getting through to The Granite Studio’s archives. Sometimes, he said, the censors don’t like his postings.

Postscript: After the massive riots in the western province of Xinjiang in July 2009, Internet censorship tightened up in China. Many websites were blocked (including Jeremy Goldkorn’s blog, Danwei). Although the Chinese government has retreated from its Green Dam proposal, censorship seems to be getting worse, rather than better. Social networking sites and YouTube are currently blocked, as is Yeeyan, the journalism translation site. At time of writing, Google is considering withdrawing from China because of an attempt to hack into the email accounts of several human rights activists. Interested readers can follow the struggle on Rebecca McKinnon’s blog RConversation or on Berkeley’s own China Digital Times, the excellent China news accumulator site run by Professor Qiang Xiao in the Graduate School of Journalism.