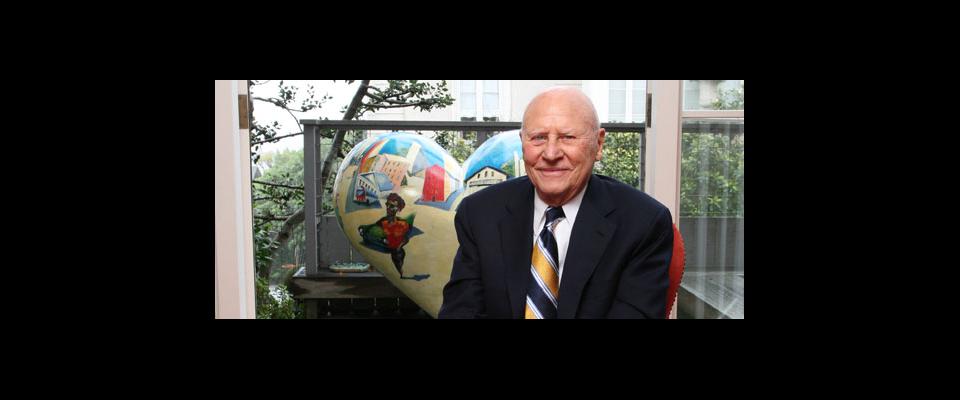

Alumnus of the Year Richard Goldman made it his mission to reward environmentalists.

Environmental philanthropist Richard N. Goldman ’41 has saved many, many places on this earth, but perhaps the most unusual is an old Burger King at the Presidio of San Francisco, the former Army base at the north end of the city.

Boarded up and slated for demolition by the National Park Service, the fast-food joint occupied an aging Army mess hall of little historical value. Yet it offered, through its floor-to-ceiling plate-glass windows, what Sunset magazine once declared “The Best View of The Golden Gate Bridge of Any Restaurant in the City.” Goldman liked the spot and arranged to lease it. In 2005, after a considerable architectural makeover, the building was transformed into the headquarters of the Richard & Rhoda Goldman Fund.

That choice of locale certainly squares with the idiosyncratic style of Richard Goldman, a lifelong Republican who supported Hillary Clinton and then Barack Obama for president. Goldman was a businessman who became a lion for the environment and a thorn in the side of oil companies.

Instead of dispensing Whoppers at the Presidio site, the organization dispenses cash—lots of it—to causes close to the heart of the 89-year-old retired insurance executive. With his late wife Rhoda H. Goldman ’45, a great-grandniece of Levi Strauss and an heir to the blue jeans fortune, the couple has given away $618 million since 1951, including $39.3 million to Cal in the past three decades. They have endowed professorships, built new facilities for athletics, and doubled the size of the Richard and Rhoda Goldman School of Public Policy. In appreciation for decades of such altruism, Richard Goldman was named the Cal Alumni Association’s 2010 Alumnus of the Year. Since 1943, CAA has bestowed this award to alumni who have distinguished themselves through service to the public good and the University.

“He and his family have been extremely generous to the University. There are very few people who have had so broad an impact,” said Chancellor Robert J. Birgeneau.

Even within the lofty club of philanthropists, Richard Goldman is his own sort of maverick. Instead of giving away the mandated 5 percent of its assets, the Goldman Fund distributes more than 10 percent. Richard has mounted a long and quixotic legislative campaign to bring the charitable giving requirement for foundations to 10 percent, with no success to date.

“Too many people concentrate on making money and never give themselves the pleasure of giving it away,” he declared in an unpublished oral history. Although age has slowed him down and made walking difficult, Goldman still has an upright “Daddy Warbucks” air about him—an elegant dresser with a broad smile, a bald pate, and a kind heart. Add to that a pair of lively blue Paul Newman eyes.

Goldman has kept up his giving even during these perilous economic times. Stock market woes trimmed the Goldman charitable assets to $273 million in 2009 from $453.3 million at the end of 2007, but the grants continue to flow.

In global environmental circles, the Goldman name is renowned. On a morning in 1988, while mulling over a newspaper article about Nobel laureates, Richard wondered whether similar awards were offered for work on behalf of the environment. Finding nothing comparable, the couple decided to create the Goldman Environmental Prizes in 1990. The annual awards to grassroots environmental advocates from five continental regions and island nations quickly became known internationally as the “Green Nobels”—and are likely to become the Goldmans’ most lasting legacy.

Originally worth $60,000, each award now carries a $150,000 stipend. Belgian herpetologist Ignace Schops is typical of the 133 “environmental heroes” from 75 countries who have won or shared the Goldman Prize since its inception. Schops was awarded the prize in 2008, in recognition of his efforts to create Belgium’s first national park.

“My first contact with Mr. Goldman was on the phone, when he was telling me I had won the prize,” Schops recalled. “His voice was calm and friendly, like he knew me already … and as a matter of fact, he did.” Schops was impressed with the dossier that the Goldman Prize staff had developed on him during the nomination and selection process—and Goldman himself was in command of the facts.

Rosa Hilda Ramos of Puerto Rico also won the prize in 2008 for her long-running battle with the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA), which operated an oil-fired generating station near San Juan. Her persistence led to a court-ordered fine of $7 million against PREPA. The money was used in part to save a nearby wetland. “Everything was like a fairy tale for me,” Ramos said of her visit to San Francisco. “I was also humbled by the struggles that my fellow recipients were involved with in their countries.”

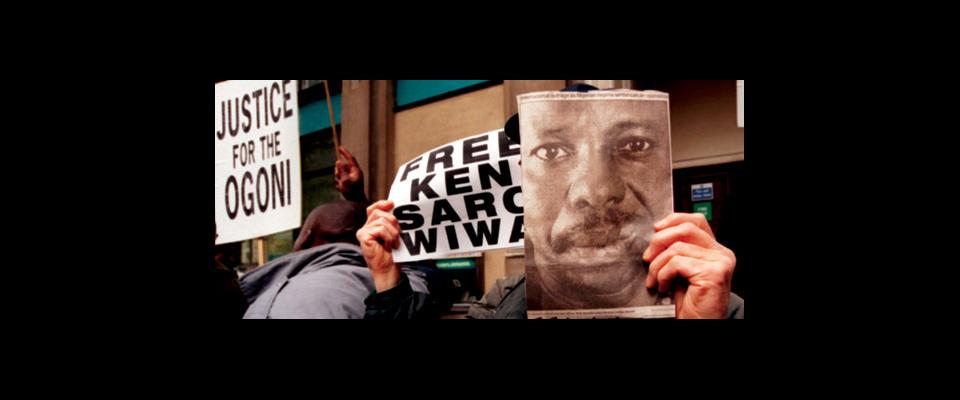

Personal risk is one of the criteria used to assess nominees for the awards. In 1995, Nigerian Ken Saro-Wiwa was unable to collect his prize. An activist who protested Royal Dutch Shell’s oil drilling on his ancestral lands, he was jailed and later executed by the Nigerian government, despite the entreaties of the Goldman Fund. “He is the only prize-winner I never met,” Goldman said during an interview at his home. “His son came to London to get the prize for him.”

In June 2009, Royal Dutch Shell, while denying any complicity in the violence, agreed as a “humanitarian gesture” to a $15.5 million out-of-court settlement with the families of Saro-Wiwa and other slain human-rights advocates. A portion of the settlement was directed to Saro-Wiwa’s Ogoni people living in the oil-rich Niger River Delta where the disputed drilling takes place.

Goldman acknowledges that his environmental zeal often clashes with the business community in which he was also a player. “Most of my friends in business or law couldn’t understand why I made such a big thing about the environment,” he said. “I was considered sort of a misfit.”

Goldman’s personal office occupies the northwest corner of the old Burger King building, with those plate-glass walls and a priceless view. His spotting telescope there can be trained on the waterfowl of nearby Crissy Marsh, or zoom in for close-ups of the fabled orange bridge a mile and a half away as the pelican flies.

Until recent health concerns restricted his mobility, Richard would visit his corner office every morning to carry on the enviable business of giving away his money. “It’s lovely work,” he told interviewer Dorian Adams, for the magazine Just Cause.

Born and raised in San Francisco, Goldman has always identified with his Jewish roots. Though he never bar mitzvahed, his faith and commitment deepened after he and Rhoda made a visit to Auschwitz in 1960. It shook them deeply, and they became ardent supporters of Israel and for Jewish community affairs. Since 1979, the Goldman Fund has contributed $102 million for Jewish affairs and $60 million to a range of programs in Israel.

Goldman’s love of the outdoors was also rooted in his childhood. His first visit to Yosemite as a 9-year-old left him awestruck. An enthusiastic Eagle Scout, he received that award from the legendary founder of scouting, Lord Baden Powell himself, at San Francisco’s Civic Auditorium. He passed that tradition on to his sons Rick, John, and Doug ’74.

In the Presidio office—amid framed pictures of himself with Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, with Vice President Al Gore, and with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton—there is a photo of family friend Admiral Chester Nimitz pinning an Eagle Scout badge on Rick. It was a moment of special pride for Goldman to see his firstborn son follow in his footsteps.

Rick, who went on to graduate from Yale University and Harvard Law School, succumbed at the age of 42 to a brain tumor. He died in Washington, D.C. in October 1989, the day after the Loma Prieta earthquake rocked the Bay Area. “There is nothing harder to accept than the loss of a child,” Goldman said in the unpublished history. “Rick’s death has haunted me every day since it happened, and will continue to do so through the remainder of my life.” In memory of Rick, Richard and Rhoda built a clubhouse at Julius Kahn Playground in a city park a few hundred yards from their San Francisco home, where Rick, his two brothers, and their sister, Susan, played as children.

Goldman also admits that he has never gotten over the loss of Rhoda, who died suddenly of a heart attack in Hawaii in 1996 at the age of 71, while the couple was battling her family over a plan to restructure control of Levi Strauss. In memory of Rhoda, Richard Goldman made a $5 million gift to the Conservatory of Flowers in Golden Gate Park, after a powerful winter storm in 1995 heavily damaged it. He was the lead donor in a campaign that raised $25 million and eventually restored the giant Victorian-era greenhouse in 2003.

Goldman is obviously pleased with his newest award from Cal, and he still remembers his undergraduate years fondly. While he pursued a pre-law course of study, he wasn’t above the hell-raising of his day. “We learned how to throw water bags at the people coming into Bowles Hall,” he said, his eyes twinkling. “We had a pretty good life.” Goldman matriculated at Boalt but dropped out after one year, deciding that he could not reconcile his conscience with the duty of lawyers to defend clients even if they have done wrong. He eventually built a career as an insurance broker.

An avid hiker who kept fit into his 80s, Goldman said he was never a good enough swimmer or javelin thrower to make a mark at Cal. His love of athletics has instead played out over the years with generous contributions. With the help of a $1.5 million grant, an all-weather Olympic-caliber track was refurbished at the Edwards Stadium complex, which includes Goldman Field, named after Richard’s father, Richard S. Goldman ’09.

Under construction and slated for completion next year is the Student Athlete High Performance Center—the same project stalled by tree-sitting protesters angered by the cutting of 91 trees at the site. The Goldman Fund contributed $10 million toward the $125 million facility. Richard was 3 years old when most of those trees were planted, and never saw it as an environmental issue. “I didn’t think much of those tree-sitters,” he said.

Cal Athletics Director Sandy Barbour said Goldman’s support of athletics reflects his own personality. “He’s a competitor through and through. He loves to win, and he loves seeing Cal athletes be successful.”

His largest contribution to Cal remains the combined $15 million in grants to expand the Graduate School of Public Policy, which was renamed in honor of Richard and Rhoda Goldman in 1997. His first donation built a companion structure across from the school’s original building on Hearst Avenue. Founded in 1969, the school is regularly rated among the top institutions of its kind. “We are training students to go into government and nonprofits, to bring with them a broader perspective on the way things are done,” said Goldman School Dean Henry Brady. “His gift made that second building possible, and allowed us to double the size of the student body.”

Goldman continues to confer with Chancellor Birgeneau and Dean Brady and participates with his children in stewardship of the Goldman charities. Rapid response, with a minimum of bureaucracy, has been a hallmark of the Goldman philanthropic style. Within hours of the news that Port-au-Prince, Haiti, had been struck by a major earthquake, executives of the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund were organizing to authorize a donation of $100,000. But board decisions can take time, so to avoid delay, Goldman was directly involved in tapping a special fund to quickly release the grants for Haiti relief.

There was an extra element of urgency that awful Tuesday afternoon in January. Five years earlier, the Goldman Environmental Foundation had awarded Chavannes Jean-Baptiste one of its six coveted Environmental Prizes, for his work in promoting reforestation and sustainable agriculture. Jean-Baptiste’s organization, Papaye Peasant Movement (MPP), is based in Haiti.

By that Friday, word had come through that Jean-Baptiste was safe. He was doing fieldwork in central Haiti at the time of the quake. The MPP staff were reportedly also safe and assisting refugees from Port-au-Prince in the Papaye training center—environmental heroes who, with some help, will go on to save what they can of a stricken island nation on a troubled planet.