Berkeley researchers are uncovering how the land looked when the Spaniards stumbled upon it.

In October 1769, the first group of Spaniards to explore Northern California by land passed through Santa Cruz. They were searching for Monterey Bay but, misled by the hyperbole of Spanish sailors, hadn’t recognized the bay even as they stood on its sands. The expedition under Gaspar de Portola was in bad shape by this time: lost and hungry, with many of the explorers dying of scurvy. At the mouth of Waddell Creek in the Santa Cruz Mountains, the priests administered last rites to several of the men.

But their luck changed a day later, when a group of Indians came to the rescue. The Spanish had stumbled into Quiroste, a large, politically powerful village in a valley near present-day Año Nuevo State Park. The villagers fed the Spaniards and provided them with guides. The scurvy symptoms improved, and a week later the expedition’s scouts became the first Europeans to discover San Francisco Bay.

“[Quiroste] was a pivotal place in the history of all of California,” says Chuck Striplen, a Berkeley graduate student in Ecosystem Sciences who is one of the leaders of an ongoing project to study the Quiroste valley. The site has become a cultural and anthropological cornerstone for our understanding of how California Indians lived before the arrival of the Europeans.

Like most large Native Californian villages, Quiroste’s population was decimated by the mission system. Mexican and American ranchers farmed and grazed the valley until the state purchased the land from a private landowner in the 1980s. Over the last few years, a team led by Striplen, Professor Kent Lightfoot, graduate student Rob Cuthrell, and State Parks archaeologist Mark Hylkema have tried to piece together the village’s history before European contact.

And there’s quite a bit there. Archaeological evidence at one site within the valley dates back more than 8,500 years. Tools and trade items found by the researchers, along with oral histories from the mission period and the accounts in the Spanish diaries, establish that the Quiroste village was widely known, influential, and rich in resources.

The project is also unique in its collaboration with modern tribes: Striplen’s Amah Mutsun Ohlone tribe and the neighboring Muwekma Ohlone tribe have considerable say in what happens in the valley. The scientists submitted their research plans to the tribes in advance and tread as lightly as possible in their fieldwork. In part because of Striplen’s efforts, Quiroste has been named a state cultural preserve—a wide-ranging designation that allows the Berkeley team to continue studying the site’s historical ecology, with the eventual goal of restoring its landscape to a condition similar to that found in 1769.

Native land-management practices are at the core of the research project. Anthropologists and archaeologists debate the extent to which Native Americans modified their environment. Lightfoot, Striplen, and Cuthrell, who will present some preliminary research in April at the Society for American Archaeology’s annual meeting in Sacramento, hope Quiroste will provide solid evidence not just for whether the land was managed, but also how and to what extent.

They’ve already reported some intriguing early findings. At a nearby site in Pinnacles National Monument, Striplen says, the team found deer grass and sedges, important basket-making materials that were likely to have been encouraged for harvest. In Quiroste Valley itself, when the state started maintaining the land and clearing brush—keeping the site more as it likely would have been before Europeans arrived—native species such as garter snakes, voles, and red-tail hawks showed up in great numbers. And with the work of Cuthrell, who specializes in ethnobotany, the researchers have noted a high number of hazelnut shells in soil samples. Hazelnut trees are uncommon in Quiroste today, but the early Spanish accounts mentioned the trees growing in the valley and surrounded by burned grass—an indication that people were using fire to encourage the growth of this food source.

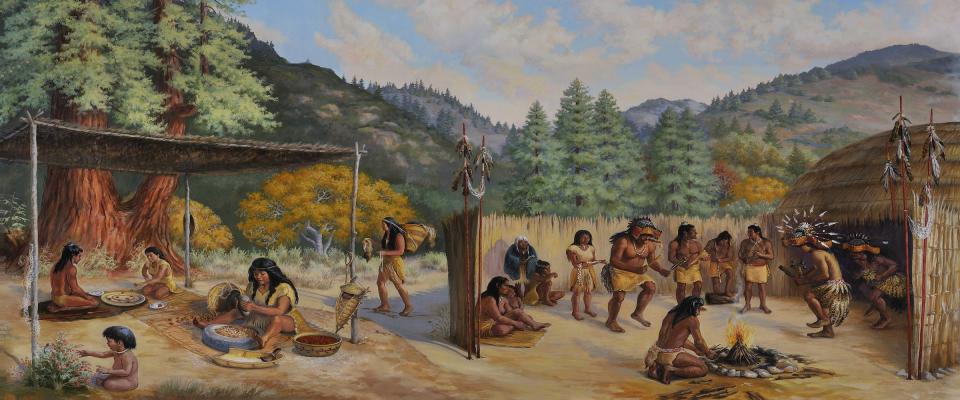

The Quiroste project has also allowed the tribes to find out more about their own history and to supplement their oral traditions with archaeology. For example, the Spanish diarist Juan Crespi described an “immense” spherical house in the area that could fit the entire town inside. The Spanish soldiers labeled the village “Casa Grande” because of it. The structure was likely an important religious building, a site for sacred dancing, and presumably similar to other round houses found throughout Northern and Central California. But how similar? And just how big was it?

“The thing about the Ohlone is, we’re the first ones to be taken to the missions in that area, so a number of our traditions, knowledge, and practices, they were broken,” says Amah Mutsun tribal chair Val Lopez. “Now we’re trying to restore them, but we do have gaps in our knowledge. That’s why we are willing to work cooperatively with the right anthropologists and archaeologists and botanists, so we can go down that re-learning path and regain that knowledge, and follow the path that our people were following before contact.”