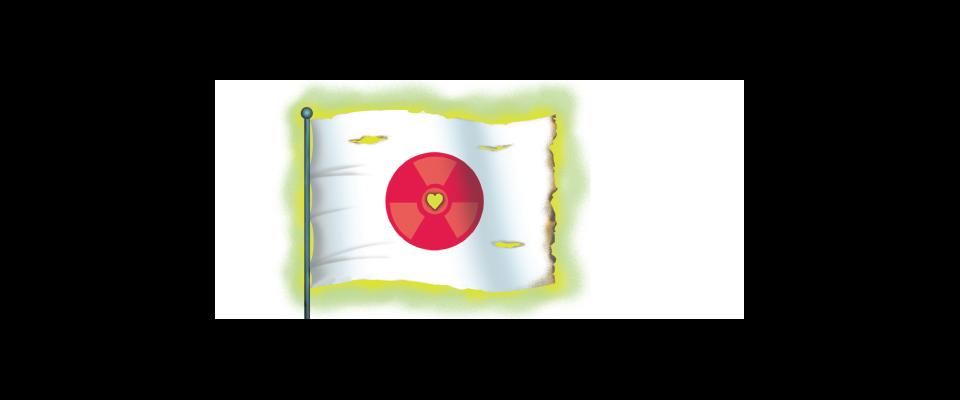

The sharply dressed man on television bows, then proceeds to talk in a soft, polite voice. I can understand perhaps a quarter of what he’s saying—mostly just conjunctions and pronouns. I miss all the essential nouns, like, oh, radiation, nuclear meltdown, and disaster. Lucky for me, he has a model of the Fukushima reactor in its current state of disintegration.

“Auntie, what is he saying?” I ask. I am in the suburbs of Tokyo on a “vacation” I had planned months ago, selecting the dates based on the cheapest fares. News of the 9.0 Tohoku quake hit the States three days before my plane was scheduled to depart. After confirming that my family and friends in Japan were safe, I spent the weekend agonizing over what to do. Would I be a burden? Would I be in danger? Would it be impolite not to go? On the phone Sunday night, my aunt, who lives some 500 miles from the reactor, assured me that I should come. She was looking forward to seeing me. So I kissed my anxious husband goodbye, left my coworkers to their handwringing, and boarded the plane.

Now, tucked into my aunt and uncle’s living room, my relatives and I are glued to the television. My aunt waves her hand. “They’re just talking about the radiation.”

Right. I get that much.

This is new territory for us. Our previous conversations had seldom strayed from everyday topics, with a strong focus on the weather. Over the years I’d developed my own peculiar lingo—Japanese slang a sassy seven-year-old boy might use (blame my three male cousins) mixed with a smattering of English. It always worked, though it did lead to social faux pas of both the amusing and embarrassing kind. And serious conversation was out.

Japan used to be my refuge, where I escaped every summer to spend lazy days with my grandpa and grandma. Here, I could eat raw mackerel or salmon roe without eliciting disgust from my peers, or go frog-catching in the mud and reenact action hero stories with my cousins.

But amid the crisis, the country now seems alien. Trains operate on slashed schedules. Staged blackouts leave areas in darkness. Some districts have started to run out of food as supplies are held up or diverted to the Sendai disaster area. There are quotas on milk and bread, both sourced from the north, and bottled water is reserved for pregnant women and infants.

I myself would have been content to stay in my aunt’s house, disrupted only by the dozen or so earthquakes and aftershocks that rumble through each day, along with thoughts of the radiation poisoning that is out there. But Auntie was determined to show me a good time. She insisted we visit Kyoto, though she wasn’t sure if the bullet trains would get us there or, more critically in my mind, back again. And despite my protests about the trouble it would cause, she confirmed the reunion with my cousins planned long ago.

And here, I realize, is the Japan I know and love—fierce stoicism in the face of disaster. Perhaps there’s a touch of hubris in the attitude that nothing can bring Japan to her knees. And yet, I feel admiration mingled with pity to hear that my cousins are so dedicated to their work that one gets only 4 hours of sleep a night as he struggles to save his company from this latest economic challenge, and that my eldest cousin spends nights in a hotel away from his family because commuting is nearly impossible.

Back in my aunt’s house, the demure anchorman bows farewell, and the screen cuts to images of devastation. Snow falls over the leveled landscape. An old man sits in a high school gym bundled in blankets, smiling even as he explains he can’t feel his fingers. A mother roots around in the ruins of her home.

My uncle shakes his head. “Oh Japan,” he murmurs, “My heart is broken.” And then he turns to me. “Let’s go out for dinner. What do you want? Sushi? Don’t hold back—anything you want is OK.”

And as we don our jackets, my aunt calls out from the kitchen, “Don’t let the irradiated rain touch you!”