If using plasma as a disinfectant sounds like the stuff of fiction, think again.

After hearing intriguing anecdotal reports about the long-lasting antimicrobial powers of water treated with plasma, Berkeley chemical engineering professor David Graves teamed up with colleague Douglas Clark to investigate. To their surprise, they discovered that the water could stay active for up to a week or more, but were puzzled as to the reason why.

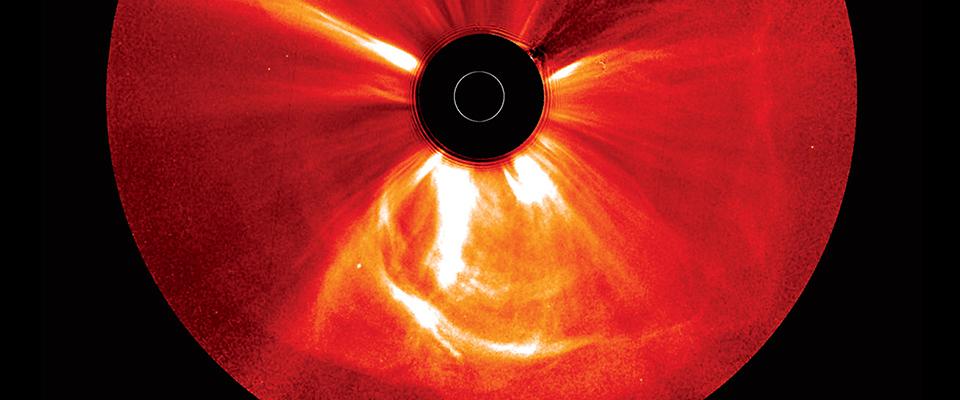

Applying an electric field to a gas makes plasma, an ionized gas found naturally in the sun and lightning, and artificially in fluorescent lamps and plasma TVs. When occuring in air, the process creates a mix of reactive molecules, sometimes called a “plasma cocktail,” that can diffuse into water a few millimeters away, making the water antimicrobial and acidic.

Graves, Clark, and their fellow researchers, including former post-doctoral fellow Matthew Traylor, graduate students Matthew Pavlovich and Sharmin Karim, undergraduate Pritha Hait, and research associate Yukinori Sakiyama, treated distilled water with plasma for about 20 minutes, and then exposed the water to E. coli for different periods of time. By counting the number of viable cells over time, they determined that although the water became less effective the longer it sat, it remained antibacterial for about a week.

The researchers thought the chemicals responsible were hydrogen peroxide, nitrates, and nitrites, known antimicrobials present in plasma-treated water. But the water continued to eliminate bacteria for seven days, whereas the hydrogen peroxide and nitrite were undetectable after just three or four days. “We concluded, whatever it was that was killing the bacteria, we probably weren’t measuring it,” says Graves. “It’s still a question mark in the whole community.”

Even so, the sustained antimicrobial effect opens up a new realm of possible applications. Graves thinks that plasmas will eventually find a place in modern hospitals, but he believes that they may be more immediately useful in the developing world. The same electronic ignition systems found in scooters or lawn mowers can be used to build cheap, portable devices for making plasmas. In rural hospitals or refugee camps, that plasma could transform water into stopgap disinfectants and antiseptics. Not bad for chemicals generated—literally—out of thin air.