Drop out. It’s such a leaden term. Yes, yes, Helen Brodsky dropped out of UC Berkeley in 1968, dashing the hopes and dreams of her Cal alumni-laden family. Before even declaring a major (she was leaning toward Russian Lit), she and her new boyfriend, John Meyer, an autodidact with a gift for tinkering and engineering, decided that unsettled times called for adventurous spirits, and lit out for the East, ending up in India.

But dropping out of Berkeley didn’t sever her relationship with the city or the campus. Helen and John Meyer married and settled back in town, where he pursued his passion for crafting innovative sound systems, long before the Meyer name became synonymous with cutting edge acoustical research and elegant, often ingenious audio products.

John had been designing speakers for McCune Sound Service when he came home one day in 1979 and announced that he’d drawn up incorporation papers with an attorney and was looking for a space to open a new research-driven company.

“It was a surprise, but in one sense it wasn’t a surprise because I knew he could do it,” Helen said. “But neither of us had ever founded a company, and I realized he’d be totally focused on technology. Our two kids were little and I had limited time. I knew that I needed to get involved right in the beginning, and my way was to plunk myself down and figure out what I could do.”

If John was going to focus on developing new patents and product lines, Helen realized someone needed to create the company’s infrastructure. The couple quickly fell into a natural division of labor—he oversees research and development and she handles business and customer relations.

Francis Ford Coppola contracted with Meyer Sound to build subwoofers for movie theaters screening ‘Apocalypse Now,’ components that put the whomp into explosions and helicopter rotors.

Also fortuitous were the time and location that put them at a cultural crossroads where rock ‘n’ roll, Academy Award–winning filmmakers, Nobel laureates, Broadway shows, and avant-garde improvised music all converged. The first folks to come calling were veteran rockers Jefferson Starship, who wanted to acquire the UM-1 UltraMonitor system (which soon became indelibly associated with the Grateful Dead). And then Francis Ford Coppola contracted with Meyer Sound to build subwoofers for a custom sound system installed in 70-mm movie theaters screening Apocalypse Now, components that put the whomp into explosions and helicopter rotors. When Coppola decided to release the film into 35-mm theaters after several weeks, the contract became moot, but the subwoofer stayed in the Meyer Sound catalog.

“When Jefferson Starship called about the monitors I asked John ‘What are we going to sell them for?’” Helen recalled. “He didn’t know. We had to create a price list and a purchasing system. There was no template for it, so I automatically drifted toward everything practical, building a dealer network, and handling all of the purchasing, marketing, and tradeshows. We’ve kept those spheres of responsibility going all these years.”

A conversation with the Meyers offers a quick study in their contrasting styles. I sat down with them in a Meyer Sound conference room on a recent winter afternoon, and like many long-married couples, they often added details to each other’s stories. With his unmanageable mane of mad-scientist hair, John is given to sudden digressions, looking off into space as he follows a train of thought down a circuitous route, which often circles back to various acoustics conundrums. Helen is warm and personable, quick to draw connections between their family and East Bay cultural institutions. Growing up as an only child in Petaluma, she identified with Cal from an early age.

“It was always known that I would go to Cal,” she said. “Both my parents graduated from Cal, and in our family education was very highly prized.”

“Mine too,” says John, whose mother earned a Ph.D. in drama from Cal. His stepfather, Charles Levy, anchored “The University Explorer,” an educational radio show that covered research associated with Cal.

“The fact that I dropped out was pretty emotional,” she said. “I hadn’t declared and was exploring a lot of things on campus. They had noon folk dancing on the field by Hertz Hall on Fridays and I got heavily involved.”

Though John never enrolled as an undergrad, he targeted information he needed through UC Berkeley Extension. “I took classes at Merritt College, and I went to Berkeley Extension for things that you couldn’t get elsewhere,” he says. “My first extension class was vector analysis. I’d be reading a book and there’s math in there I can’t read. So I figure I’ve got to go get that. Sooner or later you start to recognize the symbols.”

Located on San Pablo Avenue just north of Ashby, the Meyer Sound campus blends imperceptibly into West Berkeley’s light industrial zone. The company moved to its present location in 1982, and has gradually sprawled outward, taking over neighboring buildings while leaving the exteriors untouched, such as a manufacturing plant that takes up the north side of the historic Heinz Building nearby. Behind the nondescript beige concrete façade bearing a modest white Meyer Sound sign with the company’s sound wave logo is a rarified realm where advanced R&D takes place next to artisanal manufacturing. Several dozen patent certificates line the walls of the reception area, along with a forest of awards for various Meyer innovations.

With about 300 employees, Meyer Sound is now one of Berkeley’s largest employers, and an ongoing relationship with Cal has helped the company stay in the vanguard of sound enhancement technologies, transforming the way we experience music, theater, and even dining.

The company manufactures almost all of the interior components for speakers on site. Rather than being built in a cost-efficient assembly line, Meyer speakers are put together by a single worker who collects all the components on a cart. To ensure that each batch of speakers is as identical as possible, all the paper for speaker cones is sourced from the same stand of trees in Oregon, and the temperature and humidity are minutely controlled as the cones are molded and impregnated with resin. Before being sold, every speaker is compared to a reference speaker and if the sound reproduction isn’t a near perfect match, the new one is rejected and dissected to figure out where things went wrong. The tireless quest for consistency is Meyer Sound’s hallmark, and why their products are favored by acts and shows that want to ensure that a production in Boston sounds exactly like one in Cleveland or Los Angeles.

“They don’t want to start all over again,” John said. “Because they spend all this effort and money in the beginning with the sound designers and they just want to be able to duplicate it. If there’s no consistency, or they can’t replace something, a year later the show has to be done all over again because the equipment disappeared, so we saw a real opportunity.”

For its first two decades, Meyer Sound was widely revered in the music business for its elegantly designed, durable, high-quality work, but its systems were generally seen as geared more toward jazz venues and touring Broadway shows than rock ‘n’ roll. But orders started rolling in for Meyer’s powerful and compact MILO line array speaker system after Metallica used it on their 2003-4 return to touring. Configured in narrow curvilinear columns, these systems have become ubiquitous, delivering even, beautifully shaded sound for everyone from Judas Priest to Dolly Parton.

Meyer’s greatest technical achievement is probably SIM, which stands for Source Independent Measurement. The technique enables sound engineers to measure a sound system’s output using the music itself as the reference signal, rather than a standard test signal. The ingenious invention earned Meyer Sound an R&D 100 Award in 1992, widely considered the Nobel Prize for technological achievement.

The creation of SIM is an essential part of the Meyer legend, as John utilized Grateful Dead concerts in the research. “I love to experiment, and it’s very difficult to experiment in public places when it’s somebody’s show,” he said. The standard way of measuring systems at the time was to repeatedly send a very low level signal through, with a code, “like a bar code.” The repeated codes are then averaged together as the system measurement.

While scientists believe that audio signals at extremely low levels are inaudible, Meyer and a team of visionary engineers like Don Pearson and Bob McCarthy found that the Deadheads at shows in Berkeley and Sacramento seemed to respond to their experiments.

“Generally if a tone or voice is below the ambient level it’s very hard for the brain to hear it,” John said. “At the Grateful Dead shows we were down 100 times below anybody’s ability to hear this. After about half an hour the audience started to scream and stomp. So maybe we should stop. Then they stopped screaming. It’s just a coincidence. Let’s wait a little while and start up again. There’s no way they can detect this. It’s just impossible. They started screaming immediately. This isn’t making sense. It’s impossible, but somehow they sensed it. They can tell. We have all these ideas about how things work, but there’s so much we don’t know.” That’s one reason John disdains the widespread use of compression in digital audio, which throws away tremendous amounts of information to make sound files easily transmittable.

Meyer Sound has played an essential role in figuring out other acoustics puzzles, and the relationship with Cal has often provided a key to the solutions. Take Cal Performances and Zellerbach Hall.

When Cal Performances Director Robert Cole oversaw Zellerbach Auditorium’s renovation in 2006, he wanted to improve the sound performance so that it could seamlessly accommodate an array of acts, from solo violin recitals to symphony orchestras. He called the Meyers, and the company developed an entirely new system, Constellation, which transforms a static space into a dynamic environment, enabling the auditorium’s sound engineer to tailor the room’s acoustical characteristics at the push of a button. With Meyer engineers customizing each installation, Constellation is both a system and a service employing the company’s diagnostic algorithm, advanced digital processing, and unobtrusive transducer technology.

Since taking over as director of Cal Performances in 2009, Matías Tarnopolsky has overseen the system’s fine tuning, with each performance serving as an experiment in how to tweak the theater’s acoustical environment. “Without Constellation the natural acoustics of Zellerbach are limited,” Tarnopolsky says. “Now we have absolute flexibility when it comes to style, genre or era. The beauty of the system is that it’s a perfectly natural acoustic. You don’t realize it’s there…. You can suddenly hear all the nuances and the full expressive dimensions really come to life. The performers can hear themselves much better. The big test was the Vienna Philharmonic residency, and it showed to full wonderful effect.”

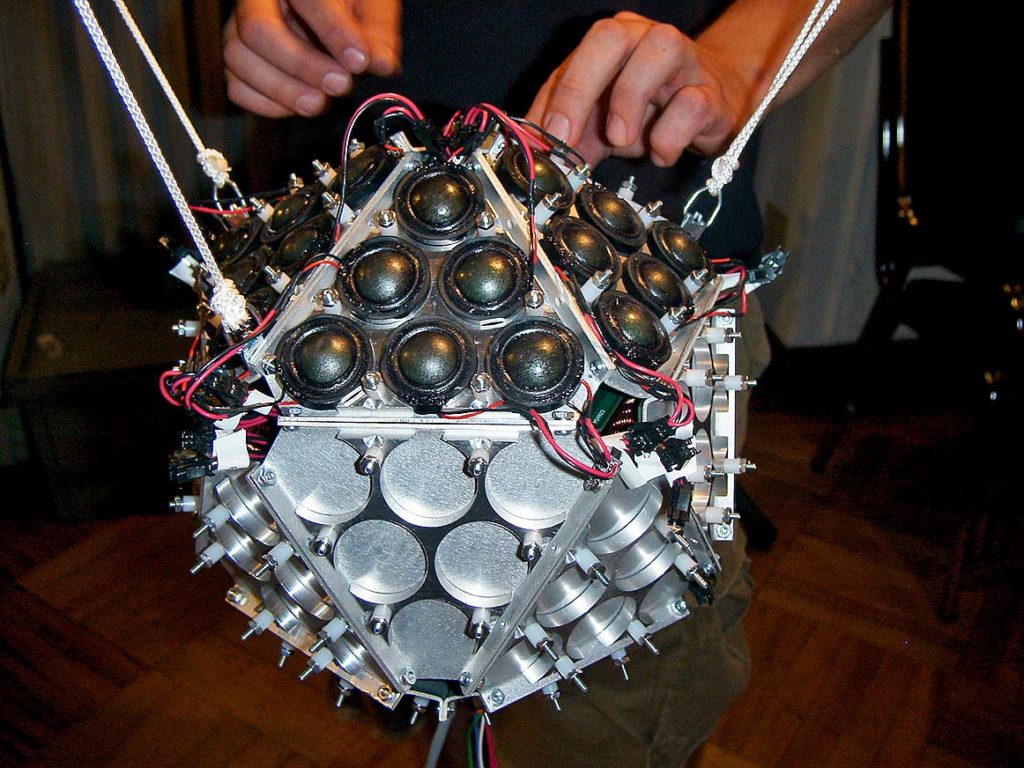

Meyer Sound’s relationship with Cal is more than just symbiotic. The late David Wessel, who founded and directed UC Berkeley’s Center For New Music and Audio Technologies (CNMAT), was a kindred spirit of John Meyer’s, and CNMAT has collaborated often with Meyer Sound on constructing devices to solve esoteric problems. Most famously, they devised a compact 120-channel spherical speaker array with programmable radiation patterns, answering a gauntlet thrown down by pioneering composer Pierre Boulez some three decades ago at an acoustics conference.

“Boulez asked why does sound through speakers sound so much worse than the instrument live,” explains CNMAT Research Director Adrian Freed, who co-authored the paper on the 120-sided speaker with Wessel, Rimas Avizienis, and Peter Kassakian. “At the time no one could answer the question because the technology wasn’t good enough. Acoustic sources in the world radiate in different directions, and loud speakers homogenize the direction.”

Working with Meyer Sound provided CNMAT with the resources and tools required to solve the problem. Other groups had attempted to build spherical arrays with 12 or 20 speakers. Freed and his colleagues discovered it required 80 to 200 speakers, and they settled on 120.

“It’s easy to write a lot of software, but it’s hard to build speakers that are exactly the same,” Freed said. “We worked over several generations of speakers, and Meyer Sound has a special rig in their lab to test things. You’ve got to have the right tools. Eventually we built it and it started attracting students. We have many Ph.D.s built around those speakers.”

Part of Meyer Sound’s value to Berkeley is that it filters research back into the community both from its own labs and from campus. Meyer Sound has ensured that Bay Area audiences get the best audio experience possible at major venues like Freight and Salvage and SFJAZZ’s Miner Auditorium as well as joints like the Starry Plough and Ashkenaz. Most recently, Meyer has even made inroads in the East Bay foodie scene, installing Constellation systems in Berkeley’s Comal and Oakland’s Oliveto. By constantly monitoring ambient sound levels in real time, the system can create different acoustical zones so that the bar fizzes with energy while booths experience a mellower vibe, all the while allowing everyone to hold a conversation without shouting. Committed to the community, Meyer has quietly contributed sound systems to schools like Berkeley High and Crowden, and Helen is serving as co-chair of this year’s Cal Performances Gala. As she describes it, doing good and doing well are mutually reinforcing.

“It’s so important to be involved locally, where we can make fast changes as needed and test new products.”

She may have dropped out, but Meyer Sound is still Berkeley inside and out.

Andrew Gilbert is a longtime music journalist whose work has appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle, Seattle Times and on KQED, among many others.