Richard Pryor was snoozing, draped across the back seat of a car driven by an erudite, bespectacled white man named Alan Farley. It was February of 1971 and Pryor was fleeing Los Angeles, trailing personal and professional casualties: three children with three different women, a few high-profile onstage breakdowns, two parents recently deceased, a flop debut album, and one angry manager who quit after Pryor pistol-whipped him in a tiff over money.

Among other demons accompanying Pryor on the road trip north was an industrial-strength coke addiction, one that would dog him most of his adult life and play a starring role in his self-immolation nearly a decade later. By then Pryor would be a full-blown superstar, hailed as a foul-mouthed iconoclast who revolutionized American humor.

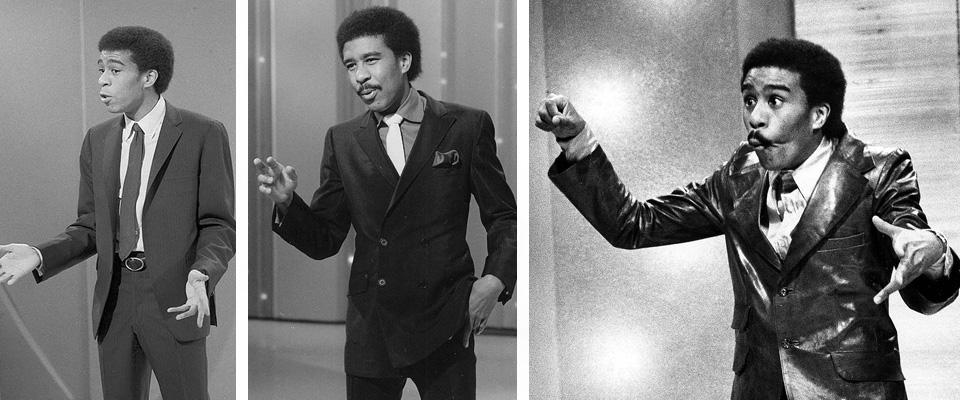

But in 1971, Pryor still hadn’t broken out of the Cosby or Flip Wilson mode—a funny black man safe enough for family-friendly appearances on Merv Griffin and Ed Sullivan, not to mention cameos in white-bread fare like The Partridge Family and ABC Movie of the Week. In LA’s after-hours establishments, his jokes had more salt, but when he’d tried to bring this material to his debut album, his manager cut much of it out.

Pryor was shaken awake by a massive 6.6 earthquake, and stumbled into the street with a bottle of whiskey and a samurai sword. He was ready to leave what he called the “valley of the damned.”

On his own and desperate for cash, Pryor had signed a multi-album deal with Laff Records in December 1970, aiming to take his comedy in a new direction. Few were prepared for this stylistic departure: He was veering wildly from white-gloved, clean-shaven punch lines to long, obscenity-laden tall tales. It didn’t help that, around L.A., he was becoming better known for his truancy than his act; the critics were no longer impressed.

Then in February 1971, at his hideaway in the Sunset Towers high rise, Pryor was shaken awake by a massive 6.6 earthquake, and stumbled into the street with a bottle of whiskey and a samurai sword. He was ready to leave what he called the “valley of the damned.”

Alan Farley presented himself as Pryor’s Virgil, though he would hardly be appreciated as such. An amiable mathematician turned radio producer, he had little in common with Pryor other than an admiration for edgy humor and a commitment to alternative media. Approaching the comic that February after a show, Farley said he lived in Berkeley, piquing Pryor’s interest—of the four remaining clubs where Pryor still enjoyed performing, one was in San Francisco and another was in Berkeley. Farley was friendly enough, and offered him a place to stay. On a whim, Pryor decided to move.

When Farley’s car exited the highway, it turned into a neighborhood off University Avenue and he parked at a nondescript white duplex on Berkeley Way. This was the beginning of what The New York Times described as Pryor’s wilderness period. “He had gone underground,” his obituary reads, failing to mention that “underground” meant Berkeley or to offer any other details. Pryor’s 1995 autobiography, Pryor Convictions, also glossed over this period.

Now, almost ten years after the comedian’s death, two new books are helping to flesh out Pryor’s time in Berkeley. The first is a memoir entitled Pryor Lives!, authored and self-published by Pryor’s friend, novelist and UC Berkeley Ph.D. Cecil Brown. The other is a full-fledged biography called Becoming Richard Pryor, by UC Berkeley English professor Scott Saul. It’s the product of seven years’ research, including 80 original interviews. Among other things, Saul’s book provides a vivid and thoroughly documented account of Pryor’s upbringing in Peoria, Illinois, where he was raised in a brothel.

The new information about Pryor’s arrival in Berkeley is a revelation, one that differs sharply from the autobiographical version, wherein Pryor says he drove up from L.A. with his buddy, fellow black comic and Berkeley local Paul Mooney. Farley is never even mentioned, an omission also flagged by Cecil Brown, who felt that Pryor “zonked” the whole Berkeley chapter in Pryor Convictions.

He picked his nose and ate it. The mostly white crowd wasn’t sure how to react. Between belly laughs and uncomfortable murmurs, audience members ordered food and walked in front of the camera. Pryor was bombing—on film.

One thing everyone seems to agree on: When Pryor re-emerged after nearly a year in Berkeley, he was different. “Richard Pryor took on a whole new persona: his own,” Bill Cosby told the Times obituarist. “Richard killed the Bill Cosby in his act, made people hate it. Then he worked on them, doing pure Pryor, and it was the most astonishing metamorphosis I have ever seen. He was magnificent.”

Pryor’s first pad in Berkeley was Alan Farley’s bed. Farley took the couch. Smart and useful, he was working as a radio producer and acting as Pryor’s de facto handler and road manager. Farley had a degree from Caltech and had come from chairing the math department at Morehouse, a historically black college in Atlanta. He also owned recording equipment and had a show on Berkeley’s KPFA radio station.

Pryor loved using Farley’s gear, and eventually got his own bi-weekly show on the station. With Farley’s assistance, Pryor was rebuilding his relationship with the microphone. Over the course of his time in Berkeley, he recorded hours of audio, some of which Farley aired on the radio, the rest of which hardly saw the light of day. Farley kept all the recordings until his death in 2012. To listen in is to hear a free-form artist exploring his strangest creative urges, obsessed with striking nerves, trying to make himself laugh in the face of painful subjects.

The first thing Pryor did in the Bay Area was perform, in a week-long engagement at Basin Street West in San Francisco—and the resounding endorsement he received from critics may have been what initially convinced him to hang around. The San Francisco Examiner’s influential critic Phil Elwood, who had panned Pryor’s act years before, was suddenly converted. He now praised Pryor for his “grace” and “perfect timing,” dubbing him a spokesman and star for the young black community, as well as “a major figure amongst contemporary hip theatrical figures of American society.” The San Francisco Chronicle’s Ralph Gleason called Pryor “the very best satirist on the night club circuit.” With reviews like that, how could Pryor not love San Francisco?

He fared less well in April, when he traveled from California to New York City for a special show at The Improv. A young director named Michael Blum had offered to film Pryor performing there, where Pryor had always found a receptive audience in his early days. But the night of the show, Pryor stood on stage with scrubby facial hair and a pack of cigarettes, fumbling his new material.

“I’m really nervous, because I ain’t had no cocaine all day. I love cocaine.” He exhaled a cloud of smoke into the microphone. “I hope I’m funny and shit,” Pryor continued, “because, just to be a nigger up here, sayin’ shit, and doing nothing … I hope my shit is funny.”

It wasn’t. At least, the audience that night didn’t seem to think so. But it was experimental. Pryor was trying out his new, rawer form of comedy—more confessional and transgressive than usual, filled with expletives and the taboo n-word. He talked about how much he loved white women. He talked about catching the clap and giving blowjobs. He picked his nose and ate it. The mostly white crowd wasn’t sure how to react. Between belly laughs and uncomfortable murmurs, audience members ordered food and walked in front of the camera. Pryor was bombing—on film. (Blum retained ownership of the film, Live and Smokin’, only releasing it on VHS 14 years later, at the peak of Pryor’s fame.) Towards the end of the film, Pryor can be heard to mutter, “This ain’t as funny as we thought it was gonna be. Motherfuck showbiz.”

Three weeks later, Pryor was killing it again in Berkeley.

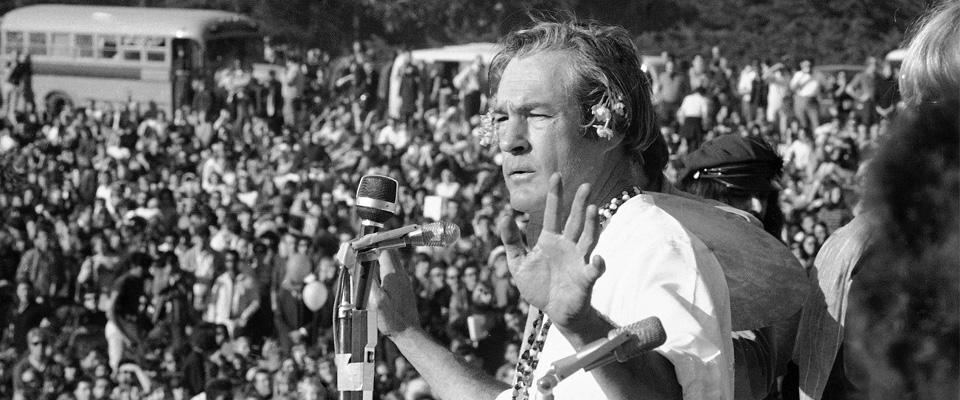

Cecil Brown recalls the “white youth who lined up to see Richard that night” as veterans of the be-ins, the core of the counterculture, who were hip to Pryor because “they had been lied to by the leaders of the nation, by the leaders of their local towns, by the Oakland Police, and by the Berkeley Police.”

Mandrake’s, a smoky converted pool hall on University Avenue, was a haven for blues greats such as Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Charlie Musselwhite, Big Mama Thornton, and Earl Hooker, who could be found on any given night sitting around a big, round table. The bar could get wild. Audiences for Commander Cody, a fixture at Mandrake’s, ceremoniously smashed pint glasses against the wall at each set. Waitresses wore hiking boots as protection against the broken glass, and the beer that flooded the floor.

On the night of May 21, the line to see Pryor stretched out the door and around the corner. Cecil Brown was there. In Pryor Lives!, he recalls the “white youth who lined up to see Richard that night” as veterans of the be-ins, “the core of the counterculture,” who were hip to Pryor because “they had been lied to by the leaders of the nation, by the leaders of their local towns, by the Oakland Police, and by the Berkeley Police.”

The room was packed and Pryor was late. Warren Widener, soon to be Berkeley’s first black mayor, was reputedly lucky to find a chair in the back. Local troubadour Country Joe McDonald was pressured into entertaining the impatient audience. McDonald has a slightly different recollection of the audience that night. He remembers gazing out at the sea of nice outfits and bouffant hairdos, and thinking, “These people must be from out of town.” He ran through his repertoire—songs like “Fixin’ to Die Rag” from his glory days with Country Joe and the Fish—but to no response. Frustrated, he offered up a chunky, improvised version of “Louie Louie.” The crowd went wild.

Finally, the bar’s owner Mary Moore pushed a befuddled Country Joe offstage and grabbed the microphone. “Ladies and gentleman, the crown prince of comedy, his highness, Richard Pryor!”

Pryor strode out, wearing a big grin, happy to have a packed house again in Berkeley. Here, his new material—anti-establishment, racially charged, and sexually blunt—struck a chord with the receptive audience.

What explained the difference between The Improv and Mandrake’s? According to Cecil Brown, “Richard arrived when the Berkeley counterculture would respect a funny guy who had a hipster’s take on everything.” Brown, author of the novel The Life and Loves of Mr. Jiveass Nigger, saw Pryor as a black folklorist working in the oral tradition, and a supreme ironist. “Pryor’s people are mine. And Juvenal’s. Swift’s, Twain’s—all the great satirists!”

Joe McDonald’s interpretation was slightly different. As he saw it, Pryor’s act provided a kind of catharsis in a time and place defined at least as much by Black Panthers as by hippies. “You have to understand,” McDonald said recently, reflecting in his North Berkeley living room, “people had never heard the word nigger before in a context that wasn’t racist.”

In the Berkeley chapter of his autobiography, Pryor talks about repeating that word—“the most humiliating, disgraceful, ugly, and nasty word ever used in the context of black people”; one that “embodied the hatred of racism as well as a legacy of hate”—in performance.

Nigger.

And so this one night I decided to make it my own.

Nigger.

I decided to take the sting out of it.

Nigger.

As if saying it over and over again would numb me and everybody else to its wretchedness.

Nigger.

Said it over and over again like a preacher singing hallelujah.

Hello, I’m Richard Pryor. I’m a nigger.

Pryor was done pandering. He wanted to change the black experience of comedy, and if it satisfied whites, too, that was even better. In doing so, he dredged up profoundly wretched feelings—in most cases, the pain of blacks and the guilt of whites—and used humor to diagnose and dispel it.

“I had heard this kind of humor all my life,” Brown marvels about that first night at Mandrake’s, “but never in public.”

One of the only black men in the audience, Brown approached Pryor in the parking lot afterward. They greeted each other with a Black Power handshake, and Brown asked Pryor how long he’d be performing in Berkeley. “I live here now,” Pryor told him. According to Brown, Pryor “said it like it was something to celebrate.”

“There were very few major episodes in his life that were not given a whole new dimension by the research I did.” Scott Saul is sitting on the couch in his office on the fourth floor of Wheeler Hall, anticipating the holiday release of his book, Becoming Richard Pryor. He’s also looking forward to an appearance on NPR’s Fresh Air—next to Oprah’s Book Club, the best book publicity an author could hope for.

Saul is eloquent on the subject of Pryor. He discourses on the comic in the way other English professors might discuss Keats or Yeats. “One thing I try to do in my book that makes it different than the other biographical treatments,” he says, “is deal with the art in layers. He became, to my mind, the fountainhead of American comedy in the postwar period, in part because he was so many different comedians rolled into one. He was the incredible physical comedian in the tradition of Sid Caesar and Jerry Lewis, who he loved when he was young. He was a great dirty-joke teller in the manner of, say, Redd Foxx. He was a great storyteller, he was a great political satirist…. As you go through his life, as you step into it, you see him add new dimensions to his act at different historical inflection points.”

Stepping into Pryor’s life was no easy task. His family has been infamously closed off to authors, and Pryor himself was aggressively wary of others telling his story for him. But after his death in 2005, many of Pryor’s old friends and family became more willing to talk. Alan Farley was one such individual. He gave Saul access to all of Pryor’s Berkeley recordings. Others, like Cecil Brown and Paul Mooney, declined to cooperate.

Asked about Saul’s book, Cecil Brown glowers. Sitting at a Berkeley restaurant with his friend Henry Fredericks, a.k.a. blues musician Taj Mahal, Brown spun for me a wide-ranging treatise on the appropriation of black culture by whites—something he insists Pryor himself understood on a deep level. “He saw how whites teach our culture,” Brown once wrote, “and yet deny us that same opportunity.”

To compound matters, Saul is also from UC Berkeley, where Brown himself began teaching in 1969 and later earned his Ph.D. Since that time, Brown says, he has watched as former students graduated, entered academia, and retired comfortably, while he himself failed to land a tenured position. He is irked that biographers such as Saul have borrowed from his writings, yet Pryor Lives! can’t find a publisher.

“I’ll tell you, I don’t see how black people make it,” Brown says. “I just don’t understand.”

Brown introduced Pryor to local black writers such as Ishmael Reed, Al Young, and Claude Brown. Pryor was enthusiastic about the new milieu but also a bit aloof. Reed remembers joining him at his apartment only to sit quietly as Pryor stared off through a haze of drugs at the daytime television offerings.

“They’re not! That’s what’s really going on,” Taj Mahal responds. “Everything is blackwashed to look like something’s going on. Then next thing you know, somebody owns the whole thing.”

When Brown speaks, it’s impossible not to hear a bit of Pryor ringing through. He monologues like late-period Pryor, flush with obscenity, pitching and stretching his voice for effect. Taj insists the echo is no accident, that Pryor rendered many of his best-known characters from Brown’s theatrics, particularly the ones that required a deep Southern accent, like the down-home, elderly ex-slave Mudbone, arguably Pryor’s most famous creation.

“It’s obvious to me,” Taj says of the influence. “I’m from South Carolina. Cecil’s from North Carolina. Pryor was from the Midwest.”

After their meeting at Mandrake’s in May 1971, Brown introduced Pryor to local black writers such as Ishmael Reed, Al Young, and Claude Brown, who admired Pryor for his skills not only as a funnyman but as an artist and thinker. Pryor was enthusiastic about the new milieu but also a bit aloof. Reed remembers joining him at his apartment only to sit quietly as Pryor stared off through a haze of drugs at the daytime television offerings.

In an early meet-up, Cecil tried to impress his new friend with a meal at the brand-new Chez Panisse, only to have Pryor insist on a steak from IHOP afterward. Still, they partied together at Brown’s house on Virginia Street, rubbing elbows with other academics, journalists, and Hollywood types. They reclined at the movie house together; they lingered in cafés, discussing race, politics, and their careers.

“All these new friends were artists who, like Richard, had found a way to turn the language of the streets into the language of art,” Scott Saul writes in Becoming Richard Pryor, “but more than Richard, they could step back and give an intellectual account of their style.”

“On his benders,” Saul writes, “Richard took to wearing an old kimono, wooden sandals, and the conical hat of a rice farmer.” He could be seen walking the city, dazed, blending in with the Berkeley weirdos.

If Berkeley gave Pryor a creative refuge, it did little to sober him up or tame his violent tendencies. Abused as a child, Pryor was an abusive adult, often physically assaulting lovers, wives, and friends. That he was able to maintain friendships despite it all is testimony to his charisma. Pryor also maintained a seemingly superhuman cocaine habit, often asking his Bay Area dealer to leave everything he had and return the next day with more. “We’d be up at dawn and going for two or three days,” Claude Brown remembered. “I used to have to keep away from him to get some sleep.”

“On his benders,” Saul writes, “Richard took to wearing an old kimono, wooden sandals, and the conical hat of a rice farmer.” He could be seen walking the city, dazed, blending in with the Berkeley weirdos. In one instance he stopped on a corner of Telegraph, opened a newspaper dispenser, and began throwing issues at passersby.

“In a city of spectacles, I became one myself,” Pryor writes in the autobiography.

He also achieved a rare independence in Berkeley, eventually leaving Farley’s pad for an austere top-floor apartment at 1988 California Street. “This is the first place I’ve ever had to myself,” he told Brown. It was bare-bones by choice, Pryor insisted in his autobiography. “If I was going to find my lost soul, I needed to cast off everything but the bare essentials. I had to renounce the past in order to discover the future. … No one knew where I was, and no one got in unless I wanted them to.

“It was the freest time of my life.”

Like his friendship with Farley, Pryor’s close association with the original Berkeley “black pack” was relatively short-lived. One day in August 1971, he packed up and moved across the bay to Sausalito to be with a new girlfriend. Shortly afterward, they split for Southern California and Pryor’s second assault on Los Angeles.

He had a new challenge, Saul writes in Becoming Richard Pryor, “how to take his Berkeley self out of Berkeley, where the outré was the norm and the avant-garde the ideal.” Berkeley was a “sideshow,” Saul writes, and Hollywood was the main event.

Will Butler is a journalist from California. He graduated from Cal in 2011.