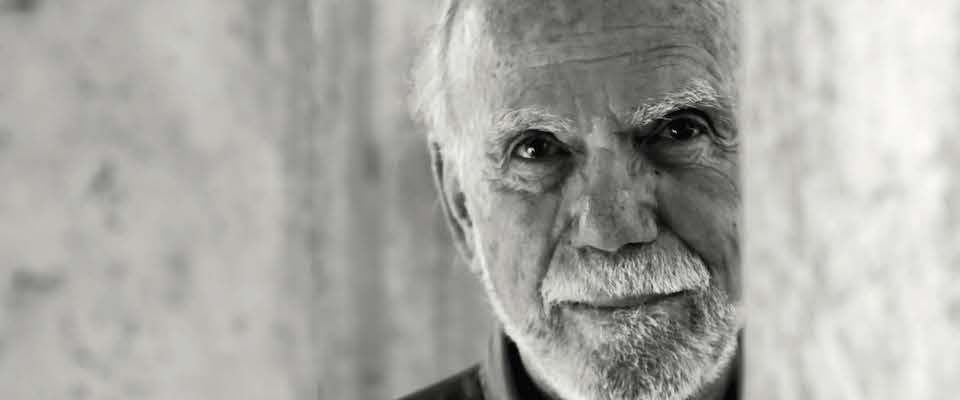

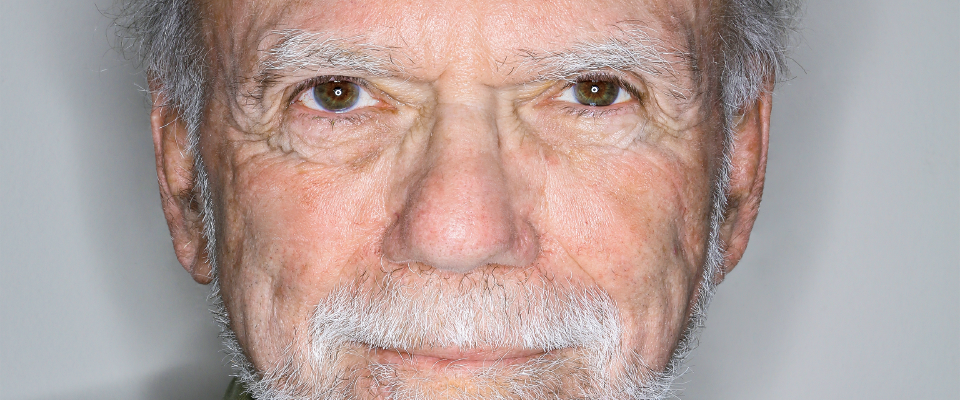

If Barry Barish ’57, Ph.D. ’63, looks familiar, perhaps it’s because we profiled him in this very same space last issue.

In that article, we took pains to explain the nature of Barish’s work as director of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO, for which he shared the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics. Little did we know we’d be featuring him again, this time as CAA Alumnus of the Year.

But, hey, fine with us. When the company’s good, who doesn’t like a second helping?

This time around, we’ve taken a less formal approach: A Q&A with the scientist about, among other things, his newfound fame, his advice to young physics grads, and (because this is a food issue) who he would invite over to his ideal dinner party.

California: As a student of physics at Berkeley, you must have rubbed shoulders with your share of Nobel laureates, people like Owen Chamberlain and Emilio Segrè. As a young scientist did you dream of joining that club yourself?

Barry Barish: Both Owen Chamberlin and Emilio Segrè were active faculty when I was a student. They discovered the antiproton in 1955, when I was a sophomore, and won the Nobel Prize in 1959, when I was a second-year graduate student. I certainly never dreamed (or fantasized) about joining their club. That was way out of my reach! But, I was a member of their “fan club,” and both of them inspired my going into particle physics.

Scientists toil in relative obscurity. What has it been like to suddenly be thrust into the public eye by the Nobel Committee? Have you enjoyed being famous?

BB: My everyday life is pretty much unchanged. My wife, kids, and friends make fun of me and complain about me, like always. I live in Santa Monica, which is full of celebrities and Academy Award winners, so what’s a Nobel Prize? But occasionally I am reminded. Some pictures I signed outside the Grand Hotel in Stockholm are now being sold on eBay, and when I give a lecture, students come up and want a selfie with me. I can live with that level of fame!

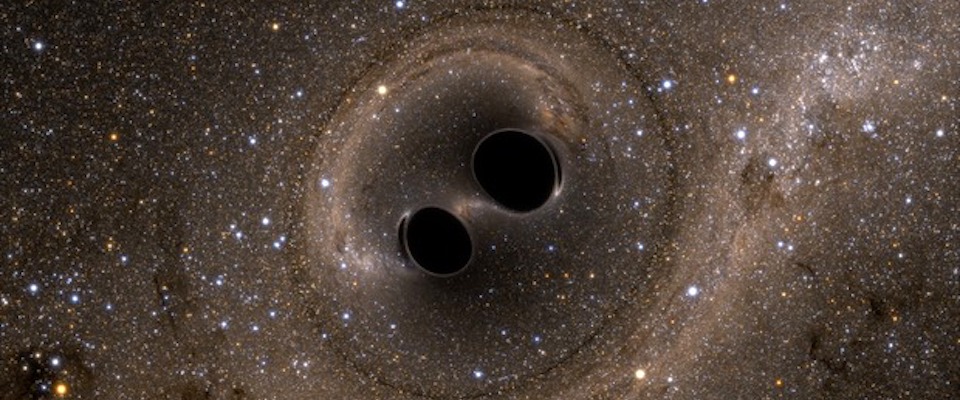

Tell us about the moment of discovery. What was your reaction on September 14, 2015, when you learned that the first gravitational waves were registered at LIGO? Was it clear that you had, in fact, detected Einstein’s long-predicted phenomenon?

BB: The event occurred at 4:50 a.m. Louisiana time, so I was sleeping. I woke up on September 14 to a string of emails. That had happened occasionally before, but this time it looked like the textbook gravitational-wave event. After digesting all the evidence and discussing it with colleagues, I did not have a Eureka moment, instead the complete opposite, a moment of PANIC. All I could think about was “How are we fooling ourselves?” or “How are we being fooled?” The first question required a lot of tests, which we did over a month or so. The second required making sure we couldn’t have been fooled by some clever hackers, who put the “fake” event into our data. A month later, I was convinced, and we wrote our paper. I must admit I let out a sigh of relief when we discovered our second event, a couple months later.

In the wake of the discovery a new field is emerging called gravitational-wave astronomy. What do we hope to learn from observing gravitational waves that we haven’t learned by peering through telescopes?

BB: Galileo first looked through a telescope at Jupiter in 1610 and soon discovered it had four moons. Four hundred years later it is mind-boggling how much we have learned about the universe using modern telescopes of all types, but always by detecting electromagnetic radiation. Now, we have a totally new way to view the universe, through gravitational radiation, which is a totally different phenomenon. With our first glimpse, we already have observed black holes directly and seen them collide, as well as observed neutron stars [dense nuclear matter] collide, revealing that these types of collisions are likely the explanation of where the gold in the ring you are wearing on your fingers originated. Ask me again in 400 years!

Since this is a food and drink issue of the magazine, allow us to ask a few questions along those lines. For starters, who cooks at home, and what is the specialty Chez Barish?

BB: My wife, Samoan, does the heavy-duty cooking and loves to cook for company. I’m the breakfast and BBQ guy. One nice thing about living in Southern California is the wonderful fruits and vegetables. I go to our local farmer’s market every week and get a mix of fruit and berries, add bananas, granola (made by my daughter) and yogurt. What better way to begin the day?

Only one question about food??? Oh, well, unsolicited, my favorite foods are Japanese and Chinese.

We can talk more about food! According to various accounts, Robert Oppenheimer took Hans Bethe, Edward Teller, and the other luminaries from his summer study conference to dinner at Spenger’s Fish Grotto in 1942, where they continued to discuss designs for the bomb. Were Berkeley physicists still frequenting the seafood restaurant in your day? Did you have your own favorite place to chat with colleagues about, say, magnetic monopoles or black holes?

BB: Interesting! By the time I was in Berkeley as a student, Spenger’s was more of a place for a fancy dinner or to take visiting parents than it was a hangout. My hangouts were Kip’s and Caffè Mediterraneum on Telegraph, and the Ground Cow or Oscar’s for (pre–health conscious) hamburgers.

At Caltech, I had lunch almost every day for 20 years with Dick Feynman in our campus cafeteria (hangout!?), affectionately referred to as “the Greasy Spoon.” A far cry from Oppenheimer’s Spenger’s days.

If you had a dinner party where you could invite any four guests, living or dead, who would they be?

BB: Fun question! I can’t do better than have a Berkeley alumni fantasy dinner: Earl Warren, Joan Didion, Timothy Leary, and Julia Morgan. I can’t quite imagine the conversation, but it would be a success anyway, because I would ask Alice Waters to make the dinner!

When we profiled you for our last issue you told us that the Barry Barish who left Cal as a postdoc was a very different person than the one who arrived here at age 17. Aside from your formal education, how did your time at Berkeley change you?

BB: My years in Berkeley were transformative. I entered as a shy young boy, good academically, but otherwise pretty lost. I found and developed the professional love of my life, physics, as an undergraduate in Berkeley, and learned how to do physics in Berkeley graduate school well enough to land a really good postdoctoral job at Caltech, which has been my professional home ever since. I also met the other love of my life, my wife, Samoan, in Berkeley, and we have made our lives together ever since, she as a psychoanalyst, me as a scientist, and with a daughter and son and three grandchildren. I left Berkeley with happiness and confidence to take on the world!

You’re now in your 80s which means that, in addition to being very smart, you are also expected to be wise. For the Cal physics students just beginning to make their way in the field today, what is your advice, in terms of both professional and personal fulfillment?

BB: Whatever you end up doing with your life, I suggest your goal should be to think of yourself as a physicist for the rest of your life, rather than just someone who majored in physics. Physics is a way of thinking, a way of understanding the world around us, a way of solving problems, and basically a way of deciding what is true. We hear of alternate truths these days, when in fact we can distinguish between them simply by using the scientific method.

What’s best about winning a Nobel Prize?

BB: The best thing about the Nobel Prize is its very effective recognition of the value of scientific discovery. Once a year, physics discoveries are on the front pages of newspapers around the world. It is recognition of LIGO and the discoveries our international group of scientists, working together for decades, have made together. Finally, individually, for me, it is the ultimate recognition that I have made an important contribution in my time here on earth.

And the best thing about being named Alumnus of the Year?

BB: Being named Alumnus of the Year is a central piece of bringing my whole life together. I attended public schools in Los Angeles, and they have recognized me, and I will be the commencement speaker next June for my high school. Now, Berkeley has also recognized me in this amazing way, and as a result, it brings together for me those formative years in my life.