Update 10/1/2018: James Allison has won the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Berkeley News Center reports on the announcement here.

In 2014, 59-year-old Brian Landers, a fifth-grade teacher in otherwise good health, began bleeding internally. After tests detected something on his small intestine, he was rushed into surgery to have it removed and awoke to the news that he had stage IV melanoma. The cancer was not only in his intestine, but his bladder and right lung, as well.

“You don’t really hear very much after that,” recalled Landers. “You just know that it’s really bad.” As he put it, the diagnosis was “almost an automatic ‘you’re gonna die.’” Indeed, patients in Landers’s condition typically have a five-year survival rate of less than 20 percent.

The researchers weren’t trying to cure cancer, per se; they wanted to understand how the elusive CTLA-4 molecule functioned.

Luckily, his oncologists thought he was a promising candidate for a new kind of treatment called immunotherapy, which leverages a patient’s natural antibodies to fight cancer cells. In recent years, immunotherapy drugs have been used to successfully treat several forms of cancer, including late-stage melanoma.

One such drug is pembrolizumab, brand name Keytruda, which was approved by the FDA in 2017. When Landers was entering treatment, Keytruda was still in clinical trials, but his oncologist enrolled him in the study after limited success with another immunotherapy drug. After two years on Keytruda, Landers was declared cancer-free.

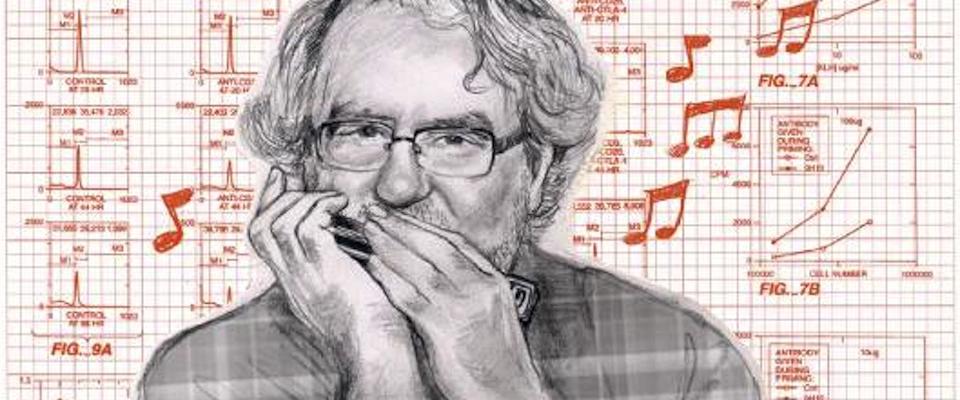

Some of the biggest breakthroughs in immunotherapy were made at Berkeley. In the 1990s, scientists at the University’s Cancer Research Laboratory, led by Dr. James P. Allison, became fascinated with the amino acid sequence CTLA-4, an elusive molecule that is expressed on the surface of an immune cell, or T cell. The researchers weren’t trying to cure cancer, per se; they wanted to understand how the molecule functioned.

Working alongside Allison, Dr. Max Krummel, now a professor of pathology at UCSF, learned that T cells, though they can attack and annihilate diseases such as cancer, are often prevented from doing so by CTLA-4, which inhibits the immune response and prevents T cells from attacking cells indiscriminately.

“What we figured out is that your immune system and your body have almost everything [they] need to defeat the cancer,” explained Krummel.

Next, they needed to learn what “buttons to push—not on the tumor, but on the immune cells”—to get them “to do a better job of eliminating that tumor.” To that end, the team created an antibody that obstructs CTLA-4, effectively taking the brakes off T cells and setting them loose on the cancer.

“Too many people just take their diagnosis of cancer as being a death sentence, and you know, sometimes they still are, but we’re making headway.”

In 2011, several years after Allison’s team successfully shrank tumors in mice using the new antibody, the FDA approved a clinical version to treat human cancers. That drug is called ipilimumab, brand name Yervoy, one of a class of immunotherapy drugs known as “checkpoint inhibitors.”

Yervoy and drugs like it have prolonged the lives of many cancer patients who would have otherwise died. According to Allison, who now chairs the Department of Immunology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, more than 60 percent of people treated with the combination of Yervoy and other immunotherapy drugs are still alive two years after treatment. When on Yervoy alone, patients who survive three years tend to make it to ten. If they get to ten, they’re usually considered cured.

“Too many people just take their diagnosis of cancer as being a death sentence, and you know, sometimes they still are, but we’re making headway,” said Allison, who has beaten three different types of cancer himself. Rather than thinking only in terms of outright cures, he thinks cancer may one day become a manageable disease, something people can live with long-term.

Not surprisingly, immunotherapy is booming. According to Allison, “every drug company is in this field,” which he notes has a new name: immuno-oncology.

Although his own research in the field marks the pinnacle of his career, Allison said it wasn’t until meeting a patient who was cured by Yervoy that he fully appreciated its impact. Her name was Sharon. She was 22 years old and had just graduated from college, gotten married, and started her career. She also had stage IV melanoma. The cancer had metastasized to her lungs, brain, and liver; a terminal case. Until Yervoy.

After receiving treatment in a clinical trial for a year, Sharon was pronounced cancer-free. Thirteen years later, she still sends Allison photos of her three children. “Before I met her, it was just numbers to me,” says Allison, “I’ve had the opportunity now to meet quite a number of people that have been affected directly, so we’ve become pretty close friends.”

As for Brian Landers, his cancer remains in remission, but it is still something he “lives with.” He gets a PET/CT scan every 12 weeks to ensure the cancer hasn’t returned. “I’ll get those for the rest of my life. You go stage IV, and your life is different forever.”

Kali Persall is a former California intern who grew up in Humboldt County. “Put me in the redwoods … and I’ll quickly regress to a more wild, existential version of myself.”