“[Kroeber’s] actions weren’t malicious, but they were flawed. Unnaming acknowledges that there was harm done.”

ON JANUARY 26, KROEBER HALL BECAME THE LATEST Berkeley campus building to be “unnamed” because of its namesake’s controversial legacy.

Alfred Louis Kroeber was one of the most influential anthropologists of his era, known for studying and documenting California’s indigenous cultures. As part of his research, he collected and authorized the collection of remains from Native American grave sites. Cal’s Building Name Review Committee cited this practice—which it notes was legal at the time, but also ethically dubious—as one of several key reasons for their unanimous recommendation to remove Kroeber’s name.

While the committee was unanimous in its decision, some faculty members argued that Kroeber’s work helped preserve Native Americans’ history in the wake of genocide.

Another reason cited: Kroeber testified that the Ohlone people were “culturally extinct,” prompting the federal government to strip the Muwekma Ohlone tribe of its land and political power. (The renaming proposal begins with an “acknowledgement that Kroeber Hall sits on the unceded land of the Chochenyo-speaking Ohlone.”)

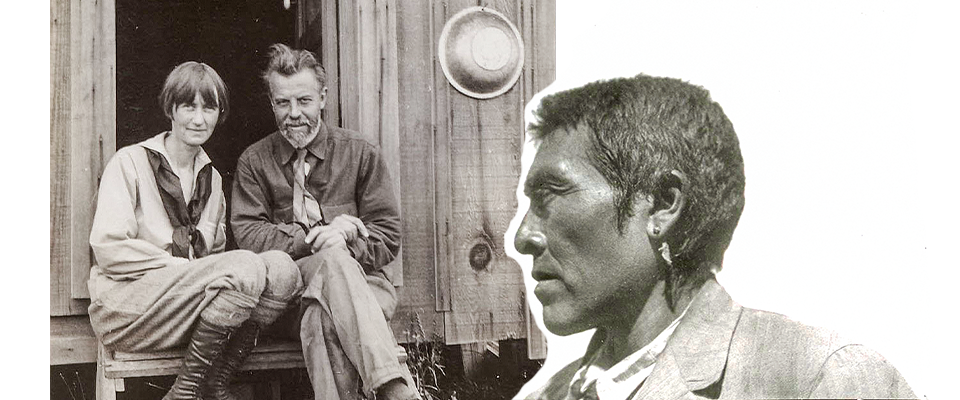

In 1911, Kroeber famously took custody of an indigenous man he called “Ishi”—thought to be the last of the Yahi people—who then worked as a janitor and performed as a “living exhibit,” as the committee phrased it, in the University’s Museum of Anthropology. Ishi was not his real name. According to the account by Kroeber’s wife, Theodora, author of the best-selling book, Ishi in Two Worlds, it was taboo to say one’s own name in Yahi culture. With no known Yahi left to introduce him, his real name was lost. Ishi means “man” in the related Yana language. Though some have raised questions about Kroeber’s treatment of Ishi, Kroeber’s daughter, the late author Ursula K. Le Guin, said the two men had “a deep friendship.”

While the committee was unanimous in its decision, some faculty members objected, arguing that Kroeber’s work helped preserve Native Americans’ history in the wake of genocide. “[Kroeber’s] goal was to document as much as he could about the cultures and languages of dozens of California tribes,” anthropology professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes wrote in an online forum. “He was neither a neo-colonialist, nor a racist, nor a fascist.” Scheper-Hughes added that, if Kroeber’s name must be removed, the building should be renamed Ishi Hall.

Most respondents to the proposal sided with the committee. Phenocia Bauerle, an Apsáalooke Tribe member and director of Native American student development at Cal, argued in a University statement that Kroeber “definitely played a part in the process that alienated California Indians …. His actions weren’t malicious, but they were flawed. Unnaming acknowledges that there was harm done.”

“This is also about how we look forward … the future needs for public housing, for racial equity and social equity.”

—Vishaan Chakrabarti

Home to the anthropology department, art practice department, Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, and Worth Ryder Art Gallery, the building will temporarily be called the Anthropology and Art Practice Building.

Three other Berkeley campus buildings—formerly known as Boalt, Barrows, and LeConte—were stripped of their names last year because of the racist and colonialist legacies of the men for whom they were named.

Another building on campus, Wurster Hall, has also had its name changed—for a different reason. Originally named for Berkeley professors William Wurster and Catherine Bauer Wurster—the husband-and-wife team who, in the 1950s, helped create Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design (CED)—the building will now be called Bauer Wurster Hall.

CED faculty hope that the updated name will more explicitly honor the contributions of Catherine Bauer Wurster, known to some as the “mother of public housing.”

“This is also about how we look forward, in terms of the issues in which Catherine Bauer Wurster was a pioneer … the future needs for public housing, for racial equity and social equity,” said CED Dean Vishaan Chakrabarti in a virtual toast to the renaming. “For us, this is both about looking back and looking forward.”

From the Spring 2021 issue of California.