Most people make mix tapes. Warren Hellman threw a music festival and invited his friends.

Warren Hellman was driving home to San Francisco from Stinson Beach a while back when he saw a woman hitchhiking. He pulled over. “I said, ‘Are you an axe murderer or anything?’

She said, ‘No, I’m OK, are you?’ So she gets in.” The car wove along Highway 1 to the soundtrack of a classical CD. The woman asked him if he liked classical music. “I said no, I like bluegrass. And she said, ‘Oh, there’s this man in San Francisco who puts on the most unbelievable bluegrass festival.’ I, being arrogant and conceited, said, ‘Do you know who that is? It’s me.’ She grabbed my arm and started kissing it.” Hellman grinned. “That was nice.”

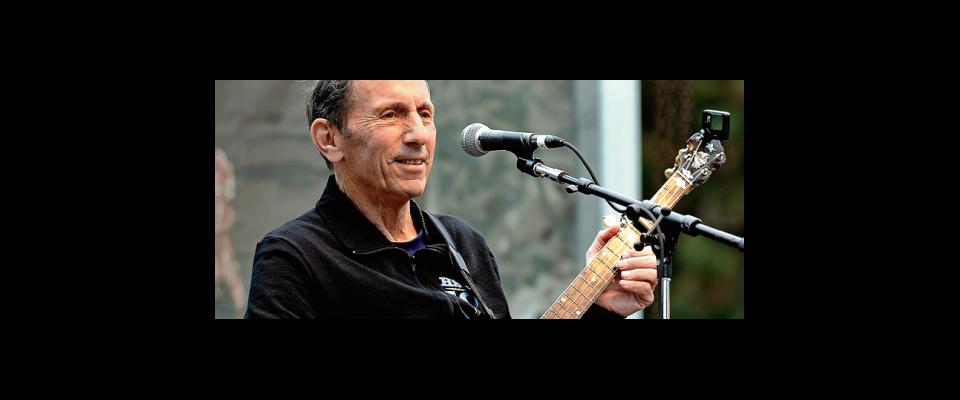

Multimillionaire financiers don’t tend to receive such displays of affection from strangers, at least not without payment. But over the past ten years, the cofounder and chairman of private equity investing company Hellman & Friedman, and scion of one of San Francisco’s premier banking families, has become one of the best-loved men in the city, particularly among the music community. And all because of his passion for an instrument that gets about as much love as investment banking: the banjo.

In celebration of the five-string (his is a 1909 White Lady), Hellman founded, financed, and, with the help of Dawn Holliday and Slim’s, put together the annual three-day music festival Hardly Strictly Bluegrass. It all started in 2001 when Hellman was a mere lad of 67. He decided to fly out some of his favourite acts, like high lonesome singer Hazel Dickens and rock/country artist Emmylou Harris, to play a concert in Golden Gate Park. Then he issued an open invitation to fellow enthusiasts to join him at the show. Essentially it was the millionaire equivalent of making and sending mix tapes; had Hellman been mad about Duran Duran and Flock of Seagulls, San Francisco might now have a Hardly Strictly Synthpop festival.

At the outset it was called Strictly Bluegrass. “Emmylou agreed to come the first year, and I really wanted her to play bluegrass—as you know, she’s pretty catholic in her music—so I thought if I called it Strictly Bluegrass she would be shamed into it. But no. We tried it again the next year: No. So we changed the name to Hardly Strictly Bluegrass, and as soon as we did, Emmylou started playing bluegrass.” Since then, the festival has only grown bigger and more eclectic. Last year the extravaganza featured more than 90 acts on six stages, ranging from flat-picking guitar legend Doc Watson to rock poetess Patti Smith. And best of all for concertgoers, the whole thing is free—no commercial sponsorships even—paid for entirely out of Hellman’s pocket.

On a cabinet in his Financial District corner office, next to a stack of CDs, is a framed photograph of Hellman posed with Emmylou Harris. On the wall hangs a decade’s worth of signed festival posters. Propped on a chair is a banjo. Were it not for the enormous desk, the people padding about in business suits, and the wall of windows overlooking the Bay, this might be the bedroom of an affluent Appalachian teenager.

One of the CDs in the stack is Heirloom Music, the new one by longhaired cosmic-country star Jimmie Dale Gilmore, a regular at the festival. Gilmore chose Hellman’s band, The Wronglers, to back him on his new collection of old-time and traditional songs. Hellman had recently returned from South by Southwest, the big music industry conference and rock festival in Texas, where Gilmore and The Wronglers played to packed crowds and enviable reviews.

“No one would have believed down in the bowels of Lehman Brothers doing IPOs that I’d ever be up here on stage with Jimmie Dale Gilmore,” Hellman told the audience in Austin’s Driskill Ballroom. Nor, presumably, would Isaias W. Hellman, founder of the first bank in Los Angeles and the first trust company in San Francisco, have believed his great-grandson would be playing a banjo on stage while dressed in a “Nudie”-style country-and-western jacket emblazoned with rhinestoned Stars of David. (“Warren doesn’t wear his religion on his sleeve,” Gilmore joked.)

Hellman admits that finance runs in his blood more than music ever did. “I never thought as a kid, ‘I’m going to be a musician’,” he said. “I knew I was going to be an investment banker; it was hardwired. And it was easy and fun. I’d sit with associates of Lehman and I’d say, ‘Why don’t you do this?’ And they’d say, ‘That’s brilliant.’ Maybe that’s what a good musician does: ‘Of course this is what you do; why do you find that difficult?’ With music with me, it’s the opposite. I say, ‘Let’s do this’ and they all look at me.”

Hellman was 28 years old and working on Wall Street in the early sixties when he decided to learn to play banjo. He bought Pete Seeger’s banjo book, leafed through it, and got his secretary to track down Seeger’s agent. “I called and said, ‘I’d like to take lessons from Pete Seeger.’ The guy said, ‘Are you crazy?’ ‘No, I’m an important guy, an investment banker.’ The guy said, ‘I’m going to hang up now.’ I said, ‘Oh no, please don’t. How do I take banjo lessons?'”

Finally he was given the name of a man in Greenwich Village, and for a while Hellman was an assiduous student. By the time the family moved back to San Francisco in 1985, however, he’d lapsed.

When he hit 70, Hellman felt the urge to start playing again and began taking lessons with Bay Area–based string multi-instrumentalist Jody Stecher. “[Warren] wasn’t a beginner, but he was pretty darn close,” said Stecher. “He hadn’t played for a number of years, and at that age your fingers have certain wear and tear, especially since horses are always landing on Warren’s hands.” (Hellman is also a passionate horseman who competes in gruelling Ride and Tie endurance races.) “But Warren has a tremendous ability to concentrate and to apply himself.”

Rather than practice alone, Hellman played with three fellow students, Nate Levine, Bill Martin, and Krista Martin. Augmented by Hellman’s assistant Colleen Browne (a former indie rock musician), Hellman’s wife Chris, and guest appearances by California fiddle player Heidi Clare, the group became The Wronglers. The band’s motto is “Simple tunes played by complicated people.”

Since forming, The Wronglers have played various clubs, folk festivals, and community centers, but their biggest gig has always been in the early fall in Golden Gate Park. Recent Hardly Strictly audiences have been enormous—numbering between a half and three-quarters of a million people (it’s hard to get an accurate count at a ticketless event). In addition to playing with The Wronglers during their regular Sunday morning slot at the festival, Hellman has performed on stage with several of his heroes, including banjo wizard Earl Scruggs and the aforementioned Emmylou Harris.

Country rocker Steve Earle, who along with Harris and others has become an annual fixture of the festival, said, laughing, “It’s funny, Warren comes from money and he’s made money of his own, and what he decided to do with it was spend it on hillbillies. It’s interesting, me being as radical and far-left as I am, and him being who he is, but through music we found common ground. He gave me credit with turning him away from the mainstream Republican Party under the Bush regime. I’ve been at the festival since the second year, when all that was going on, and I never shut up about it. When the Blue Angels used to fly over the festival I’d get the whole audience to shoot the finger, and so was Warren.”

Hazel Dickens, with her songs about downtrodden workers and evil capitalists, also found entente with Hellman. (Dickens passed away in April, just a few months after participating in this article. She was 75.) “I thought that some of my songs might be offensive to somebody who comes from a big corporation, but Warren just kind of laughs about it, he finds it amusing,” she said. “Evidently he plays the music in his office. It probably drives them people crazy.” She seemed quite taken with that idea.

Rummaging through the CDs in his office, Hellman played one of her songs, “The Mannington Mine Disaster,” about an explosion that killed 78 coal miners. “There’s a line that goes, There’s a rich man that lives on the hill, far from the poor miner’s home, for him everything is fine. After about three months of knowing Hazel, she told me, ‘I think of you as the man on the hill.’ Then a few years ago she gets up at the festival and says, ‘If Warren goes on being so nice, I’m going to have to change some of my songs.'”

Class divisions and political parties are largely beside the point, of course. As Steve Earle observed, “This whole thing exists because of something that transcends politics: Warren’s love of music.” For Hellman, at least, it also transcends economics. He recalled a promoter who approached him with an offer to acquire the event. “I said ‘Why would you want to buy it? It’s free. Anyway, it’s not for sale.'”

And it’s not going away, either; Hellman, now 77, plans to fund Hardly Strictly in perpetuity. “I always say, ‘Monet or a festival? If you had the money, which would you rather own?'”

Then, as if in answer to his own rhetorical question, Hellman added, “More than one person has described me as having no taste.”