Here in the Bay Area, where local, organic, and fresh have long been dominant adjectives as well as a prevailing ethos around what we consume, genetically modified alternatives are forcing consumers to confront a new understanding of authenticity when it comes to food and drink. And what’s brewing at Berkeley might just have beer enthusiasts clutching their pearls—or their hops.

It was 2014, and Berkeley biochemists Charles Denby and Rachel Li were hard at work developing sustainable biofuel alternatives to gasoline. Under the guidance of Professor Jay Keasling, they had been experimenting with CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology—brainchild of Berkeley scientist Jennifer Doudna—to engineer yeast to produce some molecules called “terpenes.”

By extracting sequences from known mint and basil genomes, Denby and Li were able to use CRISPR-Cas9 “molecular scissors” to splice new genes into yeast DNA.

Around that time Denby, who’d begun dabbling in homebrewing, made a critical discovery. While reading up on some homebrewing techniques, he realized that the terpene molecules that give beer its hoppy flavor were the same ones he’d been researching in the lab.

Why was this so exciting? As Denby explains, “It wasn’t going to be too big of a stretch for us to generate brewing yeast strains that were capable of making the hop flavor molecules during the fermentation process.” In other words, he could engineer yeast to make hoppy beer without the hops.

Hops have become an industry staple, and in brewing, tradition is deeply ingrained. Even though brewing methods and consumption habits have changed somewhat to match the latest trends and technologies, certain key ingredients and processes—dating back more than 4,000 years—are nearly unchanged.

That’s where CRISPR-Cas9 might shake things up a bit.

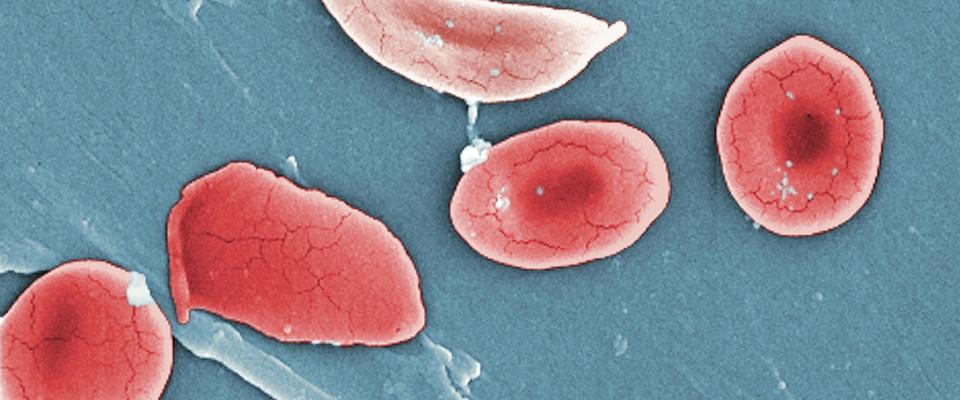

By extracting sequences from known mint and basil genomes, Denby and Li were able to use CRISPR-Cas9 “molecular scissors” to splice new genes into yeast DNA. The yeast, equipped with the genetic instructions for manufacturing hops flavor components, successfully reproduced the desired floral and citrus flavors. Just three years after the idea first occurred to him, Denby and his team had engineered a revolutionary brew, made (almost entirely) without hops.

“It was really an unknown how this was going to taste when we actually made beer with it,” Denby said, referring to a tasting he held in partnership with Lagunitas Brewing Company. “We were really pleasantly surprised that they did in fact taste hoppier than beer made without these strains. It was really exciting.”

Since CRISPR-Cas9 exploded onto the genetics scene in 2012, it has paved the way for innovations in disease treatment and prevention, antibiotic efficacy, and agricultural enhancement. And from an environmental standpoint, genetically modified hops alternatives could be a game changer for craft brewing. According to Denby, the hops needed for a single pint of beer consume nearly 50 pints of water, not to mention energy and fertilizer. From his perspective, sustainability is an issue consumers won’t be able to ignore.

“I believe that people are more likely to be accepting of the tech if they understand that it has the potential to make the brewing process more sustainable…. That’s what gets us out of bed every day.”

Could this research be the start of a new era of sustainable, hopless brewing? That’s up to the brewers, and the consumers. But Bryan Donaldson, brewing innovation director at Lagunitas and taste tester for Denby’s experiment, isn’t so sure.

“Brewers like their art, and they like to use the raw ingredients, the historical ingredients to make their beer,” Donaldson said.

Rather than replace hops entirely, he suggested brewers might use Denby’s technology as a flavor supplement. But, Donaldson added, “The trend right now is to use more and more hops. And trying to get craft brewers to not use hops at this point is going to be a bit of a challenge.”

If Denby’s technology is able to offer a “simpler, cheaper” solution, Stevenson believes it will eventually catch the attention of the macro-breweries.

With new breweries opening every day, increased demand has put a strain on local resources and the hops farmers, who are stretching to meet brewers’ needs. Which raises the question: What would less demand for hops mean for the farmers?

Mike Stevenson, local hops grower and co-founder of the NorCal Hop Growers Alliance, thinks the big brewing industry could be hit the hardest.

Brewers, he says, are heavily focused on aromatic and flavor hops—the very ones Denby wants to replace. Meaning that, from a farming perspective, hops alternatives could have a big impact on business. “If I was a commercial hops farmer, I’d be very concerned about this. I would see this definitely as a potential threat.”

Even so, Stevenson sees some room for opportunity, especially in the macro-brewing industry. Mass-produced beers such as Bud Light are some of the most hops-heavy but, compared to artisanal beers, their flavor needs are fairly basic.

“The aromatic profile of that beer is not complex,” as Stevenson explained, which makes them a great target for hops-reducing alternatives. If Denby’s technology is able to offer a “simpler, cheaper” solution, Stevenson believes it will eventually catch the attention of the macro-breweries.

Of course, artificial flavoring is hardly news to the knowledgeable consumer, who would be hard-pressed to find processed foods without added chemical flavoring of some kind. Take orange juice, for example. The consistency in flavor across Tropicana, Minute Maid, and other similar brands is due to the addition of orange essence and oil. In other words, highly processed juices rely on added chemicals to make them actually taste like the fruits from which they’re made. Is this really so different from what Denby has proposed? It’s something to consider.

Still, one other question remains: What do we lose without the hops?

Lagunitas’s Bryan Donaldson has been widely quoted for describing notes of “Froot Loops and orange blossoms” in Denby’s brew. But there’s a second half to that statement.

“I think that’s the part that’s been lost in all the press that we’ve had so far,” he said. “There were definitely fruity notes, but it did not fully replicate what hops are and what hops do for a beer. And that makes sense. Trying to replicate everything contributed by a hop flower by adding only two genes to yeast is never gonna work.”

For real connoisseurs like Donaldson, it all comes down to terroir—that special “earthiness, herbalness” from having real vegetal matter in the mix.

When asked whether he and his team had plans to work on more earthy and complex flavor bouquets, Denby said absolutely yes.

“Use less hops and make more flavor. That’s the name of the game for us.”

In the end, as with most food trends, it all depends on what the consumers want. Or at least what they’re willing to tolerate. And according to Stevenson, craft brewing has a tradition of innovation that might just quell the purists. “People want the new thing even if it’s really weird or different.”

You need only walk down the aisle of your nearest health food store to know that’s true.

California Online Editor Leah Worthington is holding out for wheat-flavored yeast.