Yesterday, we posted the first part of our profile on Grover Krantz, a UC Berkeley grad and the first credentialed scientist to publicly dedicate himself to the search for Sasquatch. Today, we take a big, bipedal step further to investigate Krantz’s earlier life—examining what shaped the man who left tracks on the field of anthropology unlike anyone before him.

Anthropologist Grover Krantz, who died in 2002, is remembered as the academic who devoted himself to the search for Sasquatch. (Read all about Krantz and his Bigfoot research here.) Though his obsession with Bigfoot and other anomalous primates didn’t start until later, his fascination with anatomy and physiology began early, as well as his tendency to flaunt his knowledge.

Krantz’s widow, Diane Horton, tells the story of the time Grover and his cousins, all preteens, went to a movie theater. Because they were all so tall, the clerk wanted to charge them the teen rate. Krantz, precocious child that he was, leaned over the counter, pointed into his open mouth and said, “Look at our teeth! You can tell we’re only 12!” For many years he toted around a small, black and white photograph of mouse entrails and later in college joyously wrote in his journal, “Beheaded a cat, then ate BIG turkey dinner.”

It was at around age 8 or 9 that Krantz really became engrossed in science and began rejecting his strict Mormon upbringing. His parents, Victor and Ester Krantz, immigrated to the U.S. from Sweden and, during Krantz’s upbringing, were pious members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake City, Utah. While his mother disliked Krantz’s open aversion to religion, they remained close her throughout her life. The same could not be said of Krantz and his father, who died when he was still in grade school.

The day after his father’s funeral, Krantz returned to school, surprising his teachers. When they told young Krantz he should be home grieving, he responded, “Not for him.”

“His dad was sort of pompous,” Horton said. “He was always right. He wasn’t really a father, but more of a dictator.” She said that when Krantz was about five years old, his father made him and his two older brothers, Victor and Eugene, stare at a blank piece of paper for 10 minutes, then asked them what they saw. Confused, they said they saw nothing, to which he responded, “No, you dummies! It’s a blank sheet of paper!”

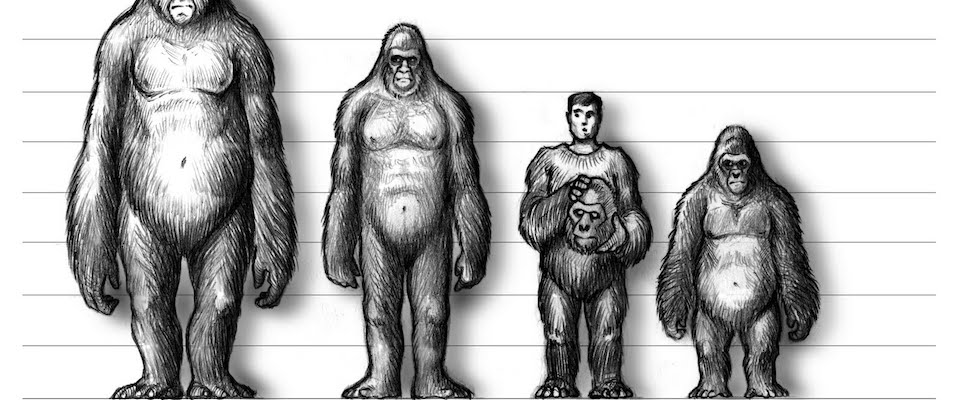

Left: Cain vs. Abel / Public Domain; Right: Bigfoot vs. Gator / Rockstaricky

Krantz didn’t remain terribly close to his brothers, mostly because they were independent men leading separate lives, but Horton said that when they spent time together, they always got along. Victor became a photographer at the Smithsonian and Eugene a military pilot who later worked in government affairs. His brothers both remained Mormon, but Krantz walked away and never looked back.

As it happens, Mormonism is the only religion that references Bigfoot as a Biblical figure. According to one famous tale, church apostle David W. Patten was attacked by a Bigfoot on a dark backroad in 19th century Tennessee. While the beast was accosting him, it also managed to lure Patten into an enticing conversation about his soul. Patten concluded that this creature was the Biblical Cain, doomed to roam the earth after betraying Abel. To this day it’s unclear if Krantz knew the story, but if he did, he didn’t care enough to indulge it.

“He got to a point—after looking at the hypocrisy of religion and how religion rejected evolution—and really moved on from it,” said author and cryptozoologist Loren Coleman, a friend of Krantz. “It wasn’t even worth arguing about or talking about.”

After graduating from high school, Krantz went to the University of Utah in 1949 but took a break from academia to join the Air National Guard as a member of the 191st Fighter Bomber Squadron. It was after this stint that he wound up at UC Berkeley, and during that time he first became interested in reports of a “giant man-like creature” in Western North America. Slowly and somewhat secretly, he began collecting data on the subject, but his interest in Bigfoot seemed an afterthought while he was earning his B.A. and M.A. in anthropology at Cal. In addition to his studies, he may have been distracted by other exploits often important to guys in their 20s—babes and booze.

Grover Krantz lights up during an interview about Bigfoot.

Krantz was famous for throwing wild parties, said Smithsonian American Indian program director JoAllyn Archambault, a Cal grad who worked with Krantz while he was a technician at the Lowie Museum of Anthropology (now known as the Hearst Museum). She said Krantz had a “titanic capacity for alcohol,” most likely because of his 6’3” frame, and that he was a legendary, friendly lush who “usually managed to make his own way home.”

“It was the 1960s and it was Berkeley,” said Archambault. “All of us at the [Lowie Museum] would have pot parties. I remember falling asleep in Grover’s backyard.”

By this time Krantz had taken up smoking cigarettes, something he would continue with vigor until he was diagnosed with the pancreatic cancer that led to his death in 2002.

“I’ve never talked to anybody that didn’t see Grover smoking,” said Coleman. “He smoked constantly. He was on Unsolved Mysteries and I know they had a hard time filming him because he wanted to continue to smoke.”

Krantz eventually put a fan in his office window at Washington State (where smoking was banned)—just so he could smoke while he worked, said Donald Tyler, a former student of Krantz’s and a professor of anthropology and sociology at the University of Idaho.

“Grover was just too weird for me,” said Krantz’s coworker JoAllyn Archambault. “But I did enjoy his company…because he was so smart and so unusual.”

“He had timed how long it’d take him to walk from his office to his classroom,” Tyler said. “So when he started the cigarette, it’d be done by the time he got to his class.”

In between the wild Berkeley hootenannies Krantz put on in his 20s, he seemed to have enjoyed the company of many different women and managed to get married, divorced, and married again before hitting 30.

“Sometimes, talking to him, it sounded like he was married to every woman in the world,” said Coleman.

Later, Krantz’s grad students would joke around about their teacher’s tendency to play marriage fast and loose, said archeologist and physical anthropologist Gary Breschini, Krantz’s former student. When Krantz was looking for an engagement ring for his final wife, Diane Horton, “the word was that he was shopping for his fourth mistake.” Fortunately, Breschini added, Horton turned out to be a real blessing.

Despite Krantz’s ladies’ man rep, Archambault said he was always a total gentleman with her, which was a good thing because she was never interested. “Grover was just too weird for me,” Archambault said with a laugh. “But I did enjoy his company and those of the other people who were attracted to him, just because he was so smart and so unusual.”

This unusualness, while off-putting to some, was like catnip for others, including Cal grad Evelyn Einstein (whom CALIFORNIA profiled a la graphic novel in the Summer 2018 print edition), and she stayed with him for over a decade. His widow, Diane Horton, was actually drawn to Krantz because of his interest in Sasquatch. In the 1980s, Horton saw an article in the paper with Krantz’s picture and sent him a letter with questions about his work. Soon enough they became pen pals, then met up at a conference in Denver. The rest is history.

When asked if she was also a cryptzoologist who would go on expeditions with Krantz, Horton said nah. She’d tag along on his road trips to Bigfoot sites and watch him interview people who claimed to encounter the creature, but her interest was purley spectatorial.

Evelyn and the dogs / Grover Krantz, Only A Dog

“When the weather was decent we would go out some place in the woods. He’d walk around and look for Bigfoot signs,” Horton said with a laugh. “And I’d look for mushrooms and flowers.”

But despite his yen for romance, women were actually in second place when it came to matters of the heart. Krantz’s most important relationship wasn’t with a girl or a mythical creature. The true love of his life was a dog.

Since Krantz was 16, he dreamed of getting an Irish Wolfhound—a breed of dog that can grow to 35 inches high at the shoulder and weigh up to 180 pounds. Something about the creature’s amazing size fascinated him. “He was a big man,” Horton said, “And he thought he should have a big dog.”

Krantz was 32 years old when he bought his first Irish Wolfhound, Clyde. He was living in Berkeley, broke and working at the Lowie. As Krantz described it, his life consisted of nothing but “a part-time job and nearly full-time drinking.” He was depressed and he needed a change, so he drove down to Southern California in a beat-up sedan, met up with an old lady, and dropped all of his savings on a puppy. It was the best investment he ever made.

Clyde lived just 10 years. “During that time he was the most important influence on my life,” Krantz wrote in Only A Dog, his memoir and tribute to Clyde. “This is not intended to underrate the influence of my last wife [Evelyn Einstein] or the beginning of my career as an anthropology professor, but it is dubious that either of them would have happened if he hadn’t been with me.”

Even though Clyde was very much a canine, to Krantz his personality made him seem “nearly human,” something that captivated him. Once, when Krantz came home wasted, he cuddled up with Clyde on his dog bed (a double sleeping bag on the floor) and soon passed out, only to find Clyde chillaxing on the human bed the next morning. “He never got another chance to pull that trick,” Krantz wrote.

When Clyde died in 1973, Krantz buried the dog next to his driveway with the intention of preserving his remains and examining his bones after he decomposed. Krantz had other dogs before Clyde and would adopt more after, but none would ever compare. When it came time to exhume the corpse, Krantz downed a gallon of liquid courage and dug him up. As he washed and brushed off the bones, the unbearableness of the experience seemed to cripple him emotionally. “Flesh of my flesh,” he murmured while scraping the remains. “I could more easily have cleaned off the skeleton of my own father.”

When Krantz was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, he coordinated with the Smithsonian museum to have his body donated, on one condition: “You have to keep my dogs with me.”

Still, Krantz refused to part with Clyde’s remains. When Krantz was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2002, he coordinated with the Smithsonian museum to have his body donated to the Physical Anthropology Division, on one condition: “You have to keep my dogs with me.” An agreement was reached, and the museum acquired his bones and those of his many dogs, along with other materials including his research papers, Bigfoot casts, etc. When he died eight months later, there was no funeral (per Krantz’s request), and his corpse was shipped to the University of Tennessee body farm (a.k.a. Forensic Anthropology Center), where researchers study human decomposition in action.

Krantz’s bones, and those of his dogs, then sat in a drawer at the Smithsonian until 2009, when he and Clyde’s full skeletons were placed on exhibit in the National Museum of Natural History. Inside a glass case Krantz’s 6’ 3” skeleton stands together with Clyde’s—the dog posed on hind legs, paws on his owner’s chest. The installation is still on view today.

And so Krantz’s legend lives on…display.

“I’ve been a teacher all my life,” Krantz said when he was asked to donate his body to the Smithsonian. “I might as well be a teacher after my death.”

Grover Krantz is hardly the only person to believe in Sasquatch. The gigantic, hairy beast has existed in Native American folklore for centuries, and there are entire communities and organizations dedicated to the search for the creature. Check out our other stories on Sasquatch, where we examine what makes people believe in mythical creatures like Bigfoot—and talk to Berkeley experts about whether such beliefs should be paid any heed.

Krissy Eliot is senior associate editor at CALIFORNIA. You can find more examples of her work and her contact info at www.krissyeliot.com.