Charles Phan is sitting in his latest restaurant on San Francisco’s Bush Street eating pancakes. “My first restaurant would have been a breakfast place,” says the 47-year-old chef, who once tried to open a small coffeeshop in Oakland. The plan fizzled when the landlord decided to lease to Starbucks.

Instead of giving up, the out-of-work software salesman and Cal drop-out decided to go epic. He dropped the coffeeshop idea and opened the first ingredient-driven, high-design Vietnamese restaurant in San Francisco. A rather ambitious plan for a guy whose only restaurant experience was bussing tables, whose only training as a cook was making dinner for his college roommates, and whose forays into the business world had flopped.

But Phan had an idea he’d been carrying around for ten years. So in 1995, backed by his family, he opened the Slanted Door, a restaurant that is now iconic and the flagship of a multimillion-dollar enterprise. “Charles is one of the most optimistic people I know,” says architect Olle Lundberg, who has designed Phan’s restaurants since 2003. “He believes in good fortune and I think he has it.”

He hasn’t always. His story starts in Vietnam, where his father took refuge after escaping communist China in 1951. He and Phan’s mother, also Chinese, opened a dry-goods store. Phan says his parents were well off and expected him, the oldest of six, to attend college in the United States. But the Vietnam War raged and the Phans lost everything under the communist regime. After the fall of Saigon in 1975, the Phans, like hundreds of thousands of South Vietnamese, fled the country.

Phan was just 13 when he, his parents, his siblings, and his aunt and uncle hid in the hull of a cargo ship with 400 other escapees. The vessel got lost at sea, he said, before being rescued by authorities and brought to a refugee camp in Guam. The family spent four tedious months there until a wealthy Guamanian couple offered to sponsor them. In exchange, Phan and his aunt went to live with the pair, providing childcare and cooking. They lived there for two years, then the Phans scraped together enough money to go to San Francisco.

Although Phan was born in Dalat, the family had always identified as Chinese. “We were allowed to eat Vietnamese food in the house, but we weren’t allowed to speak Vietnamese—only Chinese,” says Phan. So they settled in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Phan’s father became a janitor at an English pub and his mother put in zippers at the Ben Davis Co. Phan had to take care of his younger siblings and cook for the household. “I really wanted my family to assimilate into the culture,” says Phan, who pushed them along by preparing quintessential American dishes. On Thanksgiving he created a meal following recipes he’d collected from Gourmet magazine. “I wasn’t a normal high school student,” he says. “I was mostly hanging out with adults in the restaurant industry. When I wasn’t in class or working, I’d be at a café, reading The New York Times and drinking cappuccino. The other kids thought I was weird.”

Although Phan was infatuated with the culinary world, he wanted to be a potter. But his parents made it clear that art as a vocation was out of the question. He was to attend Berkeley and become an architect. So he enrolled in the program and quickly became engrossed with design. His cooking became more creative.

“I made a seven-course meal for four of my roommates and was taking reservations for breakfast,” he says, adding that he was still relying on Gourmet, but had graduated to PBS, watching endless hours of Jacques Pépin. “He taught me how to cut an onion.”

Phan stopped going to class when he got involved in campus protests and dropped out after his third year. He moved to New York City, where he got a job with an architecture firm. At night, he moonlighted as a bus boy.

In 1986, he returned home to run a sewing shop his parents had saved enough to buy. But by the early 1990s the recession had wiped them out. With no job and few prospects, Phan used some of his savings to travel, returning to Vietnam in 1992. For two months he re-explored his homeland, paying particular attention to the food.

When he came back, he got a job selling software. “I didn’t even know how to turn on a computer and here I was traveling around the world selling this stuff,” he says laughing. In 1994, the software company went bankrupt. This time Phan decided he was done working for someone else. “Once a merchant always a merchant,” he says. With $20,000 left in his savings he decided he would open a restaurant.

After losing the space in Oakland, Phan found a 2,500-square-foot building on Valencia Street. To save money he drew up his own design—a contemporary blueprint meant to dazzle. He and his family also did all the construction themselves, contracting out only the plumbing and electrical. “The bank wouldn’t even give us a loan because they thought it was such a stupid idea,” says Phan. “The space wasn’t even equipped to be a restaurant.” So he and his wife, Angkana Kurutach, pooled their resources with the rest of his family—about 20 credit cards. By the time they were done they racked up $140,000 in bills. Phan got to work on the food.

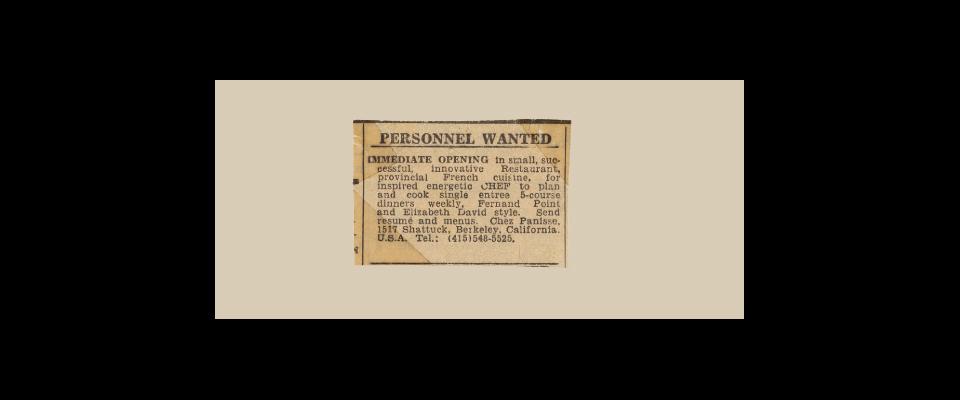

Unlike the voluminous menus of most Asian restaurants at that time, Phan pared his down to six entrees. The menu would change with the seasons and dishes would only be made with fresh ingredients. Phan would never use bottled sauces or MSG. “I was modeling it after Chez Panisse,” Phan explains. Though the farm-to-table movement wasn’t new, it had not been done with ethnic food, says Michael Bauer, long-time restaurant critic for the San Francisco Chronicle (and this writer’s boss). “And it wasn’t common at that time for ethnic food to be so high-design. It was clear that he was elevating the ambiance and the food beyond the Vietnamese genre. At that time most Vietnamese restaurants were little holes in the wall.”

Bauer was so impressed that just a few months after the restaurant opened in 1995 he gave it three out of four stars for food. “It was unusual in those days to give a self-taught cook who came out of nowhere that kind of review,” he remembers. Soon, a reservation at the Slanted Door was hard to get. And when President Bill Clinton ate there in the late ’90s it got really crazy. “I remember having to wait an hour even with a reservation,” says Frank Klein, a San Francisco restaurant owner and consultant. “Whenever my relatives come here from New York that’s where they want to go.”

Soon Phan had grown out of his tight Valencia restaurant. When developers of the newly renovated Ferry Building Marketplace along San Francisco’s Embarcadero offered him 8,200 square feet of space, the budding restaurateur worked out a deal. It was a risk, but one he needed to take if he wanted to expand the company. He opened the doors in 2004 and included a small takeout venue for a bustling lunch crowd.

The new restaurant instantly elevated the Slanted Door’s status around the globe. Soon Phan had two Out the Doors—less expensive siblings to Slanted Door, on Bush Street and in the Westfield San Francisco Centre—the Academy Café in the California Academy of Sciences, and Heaven’s Dog, a Chinese restaurant in San Francisco’s SOMA district. Even with six restaurants, he never got that little breakfast place he was hoping for. So his newest restaurant is now serving breakfast.