To say Proverb Jacobs has written his memoirs is a little like saying that Herman Melville wrote a story about a whale.

That’s not to exaggerate the literary accomplishment, only to say that when it comes to sheer bulk, Jacobs’s humbly titled, self-published Autobiography of an Unknown Football Player makes even Moby-Dick look like small-fry. The former Oakland Raider’s opus runs to nearly 1,600 pages in two volumes, including notes and index. Stacked one atop the other, they’re nearly as thick as a pint glass is tall.

I may have come up with that comparison while reading a chapter or two at Pappy’s on Telegraph, an ironic choice of watering holes. It was Lynn “Pappy” Waldorf who kicked Proverb off the 1956 Cal football squad, after the 6’4” 240-pound Oaklander broke a teammate’s jaw in a blocking drill. The newspapers made much of the “slugging” incident, but Proverb felt he’d been railroaded. “I had given the coaching staff an out,” he writes in the memoir. “Pappy didn’t know how to deal with me and took this opportunity to get rid of me.”

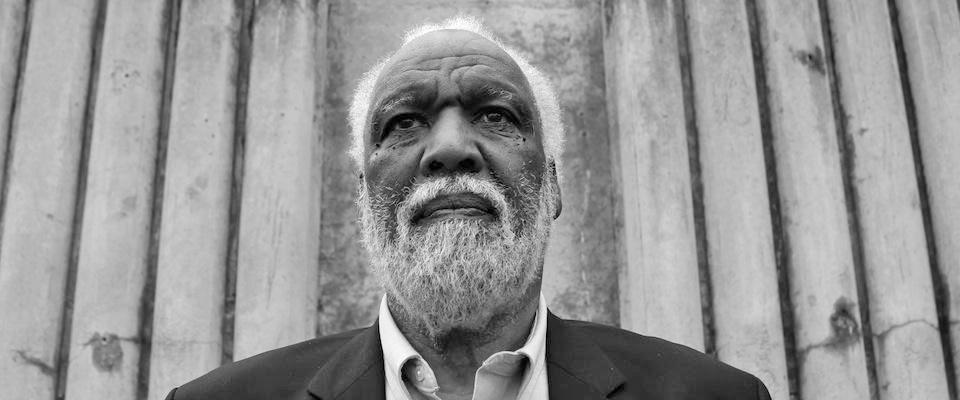

At 79, Jacobs still exudes a certain physical power. He looks as if he could crack his knuckles and make the window panes rattle. Not that he doesn’t show his age—his beard long ago turned white and he’s a bit rheumy in the eyes. He often starts a sentence two or three times before the gears mesh and he’s able to complete his thought. About his old football coaches, he says now, “A lot of people didn’t get me. I had an attitude.” There’s attitude in the way he says “attitude.”

In 1957, Proverb was reinstated to Pete Elliott’s Cal squad, but he was dropped mid-season from the starting lineup. Remarkably, he was still selected to play in the College Football All-Star Game and was a second-round pick in the NFL draft. A peripatetic pro career took him to the Philadelphia Eagles, the New York Giants, and the New York Titans before bringing him home again to Oakland, where his playing days came to an end. When he was cut from the Raiders, teammate Lee Grosscup called him “the last of the biblical tackles.”

Football wasn’t Proverb’s favorite sport. Track and field was. He was a varsity shot-putter at Cal, competing under legendary coach Brutus Hamilton, a man he viewed as a “ship of hope in a sea of pseudo-liberal racists.” After a judge tossed Proverb out of a track meet for using profanity, Hamilton was asked whether the young man would also be booted from the team. The coach, who had also served as Cal’s Athletic Director, responded: “My job is to help boys like Proverb control their tempers, and that is what I intend to do.”

To say Proverb was unhappy in those years at UC Berkeley is an understatement. The whole time, he says, he suffered a constant, low-grade headache. As the rare black student at lectures, he felt alienated and alone. “There were no pathfinders,” he recalls now. “No one to show you the way.” Still, he persisted, finishing his degree during the off-season while also working as a corrections officer in a juvenile facility. (Those were the days when NFL players also had “real” jobs.)

Ten years later he returned for his doctorate.

When I met him at his home last spring, Jacobs immediately directed me to a wall filled with framed diplomas. “Here’s my shrine,” he said. Here were his alma maters: Oakland Tech, Modesto Junior College, San Francisco State, Cal. The doctorate in education from the University of California, Berkeley held pride of place. He said, “I wasn’t supposed to graduate from high school.”

Proverb went on to teach and coach at Laney College in Oakland, where he started the first women’s track program and mentored world-class runners such as James Robinson and Charonda Williams. He also worked as a scout for Bill Walsh’s 49ers.

The genesis of the autobiography was a question from Proverb’s granddaughter. They were in the Oakland Public Library at the microfilm reader when the little girl looked up and asked, “Poppa, where do we come from?”

“I didn’t have an answer,” Jacobs recalls. “So the next time I saw her, I said, ‘Poppa’s gonna trace our family back to the beginning.’” The research, spread across 20 years, led back through the bottomland parishes of Louisiana to what is now Cameroon on his mother’s side, and Nigeria on his father’s.

The family names alone are things to conjure by. There are biblical ones like Amos, Abel, and Abraham, and Creole ones like Narcisse, Hilaire, and Marceline. And others that are just plain fun to look at: Lillie Dauzat, Ransom Venson, Miss Creecy Griffin. And you thought “Proverb Jacobs” was good.

His great-great-great-grandfather, the first of his ancestors to be brought to America as a slave, was Ebus, better known as Jaco Congo. Jaco begat François, who married Clarese Clara Laborde, whose son Jean Baptiste (later known as John the Baptist or J.B.) was Proverb’s great-grandfather. Among other things, John the Baptist’s story serves to remind readers just how recent America’s slave past really is. J.B. died in 1947 at age 103. On Emancipation Day, he would have been 20.

Proverb himself was born in the town of Marksville, Louisiana, in 1935. He was just a baby when the family relocated to California. “We moved to a tough neighborhood in West Oakland, populated by Portuguese, Mexicans, Italians, Chinese. We all had one thing in common: We were poor.”

Proverb took what you might call the “kitchen sink” approach to writing; he threw everything in. When people complain about the length, he shrugs. “What would you have me leave out?”

His dad had been a “stump-barber” back in Louisiana, so called for the practice of using stumps for barber chairs. In Oakland, he broke the color barrier at Moler Barber College. “He could cut white people’s hair and black people’s hair,” Proverb says, laughing. In high school, Proverb would hang out at the shop, shining shoes while his old man cut hair. When business was slow, he read books.

As we spoke in his study last May, he would start to tell stories like these, then cut himself off, point to his books and say, “It’s all in there.” No kidding. Proverb took what you might call the “kitchen sink” approach to writing; he threw everything in. When people complain about the length, he shrugs. “What would you have me leave out?”

In truth, there’s plenty that could have been cut. A professional editor would have thrown reams in the trash—the official letters, the long passages from newspaper articles, the scores from inconsequential games, his recitations of chart-toppers (from 1950, 1951, 1952, etc.). An editor would have insisted on pesky things like transitions, and on weeding out the repetitions.

Despite being an editor myself, I was able to overlook the flaws and appreciate the book’s idiosyncrasies—and those of its author. I found his love of high school choir both surprising and endearing, and was tickled when he went on for pages about his cat, Boots. I appreciated the news clippings (about everything from the Olympics boycott to the murder of Malcolm X) for the way they captured the swirl and tumult of the times he lived through.

I also came to savor the book’s sly humor. A few examples:

Of a fistfight at Oakland Tech involving an upperclassman named Ronald Dellums, Jacobs reports only, “I didn’t lose.”

Of a friend in Philly, he writes that he was “into loaning people money,” before adding with mock innocence that this same friend would sometimes ask Proverb to “go with him when he had to see people” about said money.

In Cleveland to play the Browns, he writes about the cold of Lake Erie: “When the wind from the lake hit me, I had to look down to see if I had any clothes on, it was so cold. I had on a corduroy suit, olive drab. I thought that I looked sharp.”

I came to think of some of these as Proverb-isms—statements that, wittingly or not, have a kind of koan-like resonance. Here he is describing his new roommate with the Raiders, Howie Williams:

This was something new to me. I was always the odd Negro on the squad because whites and Negroes didn’t room together at the time. Howie had graduated from Howard University (the “Black Harvard”) in Washington, D.C., with a degree in Electrical Engineering. We were very compatible. He didn’t do a lot of talking about nothing. Since I didn’t do a lot of talking about nothing, either, it was great.

After he was cut from the Raiders in 1964, Proverb writes that he would often drop by the Berkeley campus, then roiled by protests, to pay his old track coach a visit. “I knew where to find Brutus. He would be sitting in his customary spot leading down to the track from the bleachers. He was the only person at the University that I had any feelings for.… Sometimes we wouldn’t talk that much—we would just be in each other’s company.”

And there it is: A story where nothing happens. An image, really, a Zen moment—the sound of two men “not talking about nothing.”

Would you have had him leave it out?

Pat Joseph is editor of California magazine.

From the Winter 2014 Gender Assumptions issue of California.