The 50th anniversary of iconic rock magazine Rolling Stone arrived in November, and the party was long and loud. Origin stories have festooned the magazine and its website; a coffee table book appeared in May; Joe Hagan’s biography of cofounder Jann Wenner, Sticky Fingers, was published in October; and an HBO documentary is scheduled for November. To keep things interesting, Wenner announced that he plans to sell his company’s stake in the magazine, prompting a round of retrospective articles in The New York Times and elsewhere.

When recounting its own past, Rolling Stone routinely features its San Francisco origins. From the outset, the magazine called “the journalistic voice of its generation” attached itself to the city and its Summer of Love. Hatched in a San Francisco loft space shortly after that season, Rolling Stone touted Jefferson Airplane and covered the Grateful Dead drug bust at 710 Ashbury Street. Well before that, cofounder Ralph J. Gleason was featuring the Haight’s vibrant music scene in his San Francisco Chronicle column.

But if Rolling Stone was a creature of the San Francisco counterculture, its success can also be traced to its Berkeley roots. According to Hagan, Wenner’s years at Cal had a profound effect on the magazine’s origins and development. Early contributors and editors—including Greil Marcus, Charles Perry, and Jon Carroll—were Cal alumni, and their stances on politics, drugs, and music were staples in the magazine’s unique editorial formula.

“The Berkeley network was central to the development of Rolling Stone,” Hagan said.

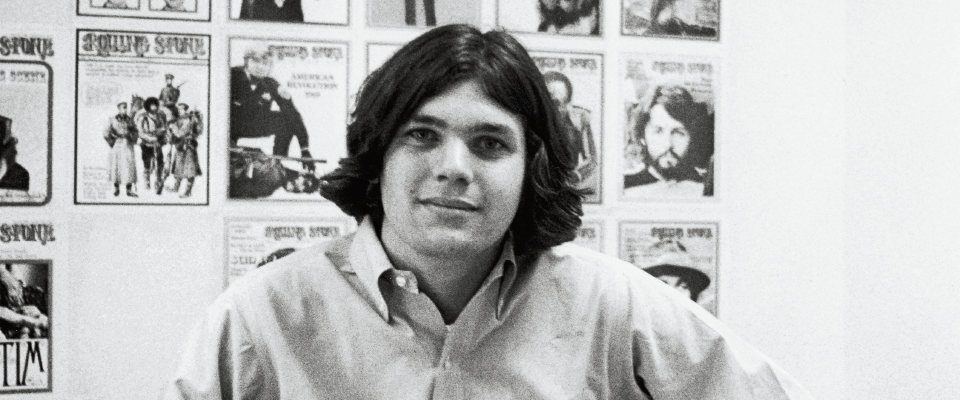

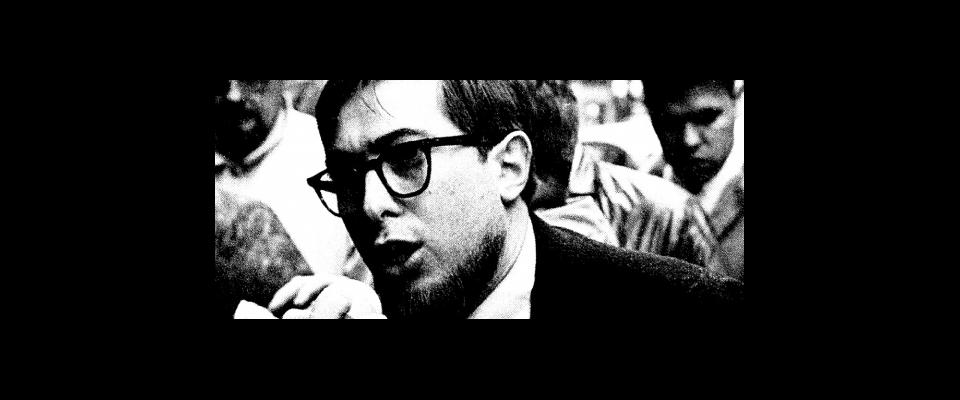

That network began to take shape after Wenner enrolled at Cal in 1963. An English major and political science minor, he was also an editor for SLATE, the student political party that helped launch the Free Speech Movement (FSM). In his spare time, Wenner worked at the NBC radio affiliate KNBR, where he eventually covered the Berkeley campus. He was reporting from the Greek Theatre in December 1964 when police hauled off FSM leader Mario Savio after he tried to respond to UC President Clark Kerr’s address. An AP photograph shows Wenner in a trench coat, microphone in hand, only yards behind the apprehended Savio.

In 1966, Wenner began writing a column called “Something’s Happening” for the Daily Californian. One of its readers was budding culture critic Greil Marcus, who met Wenner through his dormitory roommate in 1964. Marcus recalled that Wenner’s columns were “full of ridiculous acid fantasies” as well as “trenchant views about music and politics.” When added to his studies, reporting, and relentless social networking, Wenner’s columns also signaled his immense drive. According to biographer Hagan, many of Wenner’s friends from that time described him as the most ambitious person they had ever met.

Berkeley’s influence on Marcus, who grew up on the peninsula, ran even deeper. An American Studies seminar taught by Michael Rogin and Larzer Ziff fired his imagination. Rogin was open, charismatic, and not much older than the students; Ziff was more rigorous but was equally inspiring. The class met in a library seminar room, which Marcus described as “the most marvelous place imaginable.” He and his classmates completed their homework there, often staying past midnight to discuss American history, politics, and culture. Afterward, they used a rope to rappel down from the third floor of the closed library. It was “an atmosphere of great intellectual intensity,” Marcus recalled. “The questions were real, part of everyday life.”

Marcus saw strong and direct links between that course and the Free Speech Movement. “Everything we were doing in that seminar was playing out in public,” he said. After one class, he and his fellow students wandered down to Sproul Plaza, where they saw a police car surrounded by hundreds of students. Jack Weinberg, arrested for violating campus restrictions on political activism, sat handcuffed in the back seat. Beginning with Savio, speakers mounted the car and argued the merits of those policies. The entire experience, Marcus said, “made knowledge concrete, real, open, and open-ended.” It also shaped his life and his work.

“The Free Speech Movement had an enormous effect on everyone and in many ways,” Marcus said. “We measured ourselves against it and its values. Rolling Stone wouldn’t have happened without the Free Speech Movement. Everything that I had learned at Berkeley, that I had learned to care about, there was room for that at Rolling Stone.”

In May 1966, Wenner met Ralph J. Gleason at a Grateful Dead concert in Harmon Gym. Gleason had no formal affiliation with Cal, but he “was always involved in University life,” said Marcus, and Wenner was flattered to learn that the columnist was aware of the younger man’s work at the Daily Cal. After witnessing Savio’s arrest at the Greek Theatre, Gleason devoted one of his Chronicle columns to the incident. He also hosted Wenner and others at his Ashby Avenue home, which served as a kind of salon. In the early 1970s, Gleason became the only music journalist to land on President Nixon’s infamous Enemies List. Gleason considered his inclusion a major honor and posted a story about it, circled in red pen, on a wall in his home.

Despite Gleason’s stature (or perhaps because of it), he became a target for Marcus, whose early articles included digs against the veteran columnist. “My view,” said Marcus, “was ‘Let the young guys take the floor now. Let the old guys shuffle off the stage.’” But when he needed a photograph of The Coasters, he called Gleason, drove over to his home, and was invited inside. Gleason indicated that he was familiar with Marcus’s work, including the digs, but he thrilled Marcus with the free-ranging conversation that followed. “I left walking on air,” Marcus recalled.

Wenner dropped out of Cal in 1966, and Gleason arranged a position for him at Sunday Ramparts. The newspaper was a spinoff of Ramparts magazine, the legendary San Francisco muckraker where Gleason was a contributing editor. Marcus continued to follow Wenner’s writing there. “He had an article on Herman’s Hermits and how terrific they were,” Marcus said.

Wenner lost that job when the newspaper folded. Gleason resigned from the magazine over its March 1967 cover story, “A Social History of the Hippies.” He thought the story misleading and inaccurate, and his anger turned to fury when when no one at Ramparts responded to his resignation letter.

Gleason insisted that the magazine “either go out of business right now or else cover Altamont like it was World War II.”

While visiting with Gleason that summer, Wenner proposed a new magazine. Gleason, who was writing an article called “Like a Rolling Stone,” responded favorably and suggested Rolling Stone for the title. Wenner contacted the Ramparts art director and lifted some design elements from that magazine. When Marcus saw his first stack of Rolling Stone magazines at Whelan’s Smoke Shop on Bancroft Avenue, he sensed Wenner was behind it.

Rolling Stone’s professional design outclassed CREEM, Crawdaddy!, and other early rock magazines, and its countercultural emphasis distinguished it from trade publications and fanzines. Its album reviews, however, failed to impress Marcus, who complained to Rolling Stone associate editor Charles Perry. Perry had transferred to Cal from Princeton, became involved with SLATE, and graduated in 1964 with a degree in Middle Eastern studies. (During his senior year, he lived in North Berkeley with LSD kingpin Owsley Stanley, who later became the Grateful Dead’s patron and sound engineer. Stanley’s girlfriend, Melissa Cargill, studied chemistry at Cal and played a major role in LSD production. “He was at pains to show that she didn’t do all the work,” Perry recalled.)

After graduation, Perry attended dance parties in San Francisco, sampled psychedelic drugs, and worked for the Cal psychology department in an animal facility off Grizzly Peak Boulevard. He connected with Rolling Stone through another Cal roommate and friend of Gleason. Perry began as a proofreader at the new magazine, but when his former roommate entered a treatment center for heroin addiction, Perry replaced him and quickly worked his way up to associate editor.

Within days of contacting Perry, Marcus received an offer to edit the magazine’s Records section for $35 a week. A graduate student by that time, he accepted the offer and debuted his section in July 1969. Later that year, he attended the Altamont Speedway Free Festival and contributed to the “Let It Bleed” issue, which investigated the concert’s feckless planning and lethal violence. That coverage landed Rolling Stone one of its first National Magazine Awards. Behind the scenes, much of the credit went to Gleason, who insisted that the magazine “either go out of business right now or else cover Altamont like it was World War II.”

Jon Carroll, best known for his long-running column in the San Francisco Chronicle, joined Rolling Stone the following year. After arriving at Cal in 1961, he had written for the Daily Cal and edited the California Pelican, the campus humor magazine. When his summer internships at the Chronicle yielded a full-time position in 1963, he dropped out of Cal but continued to live in Berkeley and was present for many of the Free Speech Movement’s key events. At the Chronicle, he edited Gleason, who asked if he’d like to join a new magazine he was forming with a young friend. Carroll declined but followed up six months later. He worked on another Wenner publication, Earth Times, but switched over to Rolling Stone as an assistant editor after that tanked.

Carroll said his time at Cal affected his ideas about sex, politics, civil rights, and seemingly everything else. The whole scene, he said, was “unbelievably seductive.” For him, everything seemed connected to everything else—including marijuana, which “somehow was involved in stopping the war in Vietnam.” In addition to capturing that spirit, Rolling Stone hired good writers and “didn’t look like it was thrown together in the backseat of a station wagon.”

Rolling Stone’s audience and reputation grew rapidly. “Being the premier rock magazine wasn’t a coveted title in 1967,” Carroll said, “but it was a big deal ten years later.” He didn’t make it that long. Six months after Carroll joined the staff, Wenner decided that the magazine was too focused on politics. He fired several staff writers and moved Carroll to yet another magazine, the short-lived Rags, which focused on counterculture fashion and shut down in 1971. Wenner’s decision to downplay politics was also short-lived. In 1971, he named Hunter S. Thompson chief of the newly formed National Affairs desk. Thompson’s gonzo dispatches from the 1972 presidential campaign further distinguished Rolling Stone from its competitors.

In 1975, Rolling Stone showed that it could break major stories. After the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) kidnapped Cal undergraduate and media heiress Patty Hearst, the magazine ran a two-part investigative story written by Howard Kohn and David Weir. It traced Hearst’s abduction, her decision to join the SLA, the communiqués aired by Berkeley station KPFA, and Hearst’s participation in SLA bank robberies. Unlike other accounts, however, Rolling Stone’s also told the inside story of Hearst’s time as a fugitive. Kohn and Weir met one of their unnamed sources, Jack Scott, through civil rights attorney and Cal alumnus Michael Kennedy; Scott then introduced the two writers to other key sources. At her trial, Hearst testified that Scott, who held a Ph.D. in sociology from Cal, drove her east in the summer of 1974 and then back to Las Vegas. Scott admitted that he had sheltered Hearst, but when her memoir linked him to terrorist groups, he received $30,000 to settle a libel suit.

Selling the story to Rolling Stone was an easy decision, Weir said: “They paid the best, had the biggest audience, and they were local.” Both Weir and Kohn already wrote for the magazine and admired its freewheeling style. Wenner was eager to publish the story, which was immediately denounced by leftists and the Hearst media empire. And according to Weir, the FBI was incensed because it knew less about Hearst’s underground activities than the magazine did.

By the mid-1970s, Rolling Stone occupied a unique niche in the national media. Its political stories reflected its Berkeley roots, but it could also tap a reliable advertising base—namely, the music industry—that political magazines couldn’t. (Ramparts ran through two private fortunes before folding for good in 1975.) In effect, Rolling Stone’s rock coverage subsidized its political material, which could not have survived on its own. None of this was planned, Wenner insisted, and Rolling Stone never had a business model as such. Instead, it had a point of view and a mission. That combination, he said, drew a large readership, which then attracted advertisers.

Rolling Stone moved to New York City in 1977, two years after Gleason’s death at age 58. San Francisco’s status as a global rock capital had diminished, and Wenner felt NYC would be a better location in which to consolidate. By that time, several Berkeley writers and editors had moved on. Marcus wrote Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘n’ Roll Music in 1975, launching his career as a cultural critic. Perry resigned in 1976 to write a history of the Haight-Ashbury scene. Having attended potluck dinners in the 1970s with Alice Waters and Jeremiah Tower, Perry later became a food writer for the Los Angeles Times. Carroll worked for a series of magazines after Rags folded, rejoined the Chronicle as a daily columnist in 1982, retiring in 2015.

Fine acknowledged that balance and strict objectivity have never been Rolling Stone’s calling card. The magazine, he said, “isn’t afraid to write from a specific point of view or put its passions on its sleeve.”

In New York, the Berkeley network’s influence waned but never disappeared. Several longtime Cal faculty, including journalism professors Timothy Ferris and Lowell Bergman, published their early work in Rolling Stone. Its current managing editor, Jason Fine, is a Berkeley alum. Fine, a Laguna Beach native, said he and his father bonded over their shared interest in Rolling Stone. While writing about music for the Daily Cal, Fine would flip through Wenner’s early clippings and morgue files. After finishing his degree in history, he attended the Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism and described his thesis, an investigation of pot farming on public lands in Humboldt County, as a Rolling Stone–style story.

Asked about the magazine’s niche today, Fine noted that its biweekly publication schedule allows it to run news stories that monthlies can’t. “Rolling Stone remains this very interesting mix of things,” he explained. “It’s a newspaper inside of a magazine, with long-form features as well as pop culture, music, and politics.” Much of its relevance now flows from its award-winning political coverage. In 2006, it landed a National Magazine Award for a story about the Bush administration’s public relations campaign on behalf of the Iraq invasion. Two years later, another National Magazine Award was granted for Matt Taibbi’s edgy political commentary. Since 2010, the magazine has collected two Polk Awards for journalistic excellence—one for a controversial profile of General Stanley McChrystal, and the other for a report on war crimes in Afghanistan.

Fine acknowledged that balance and strict objectivity have never been Rolling Stone’s calling card. The magazine, he said, “isn’t afraid to write from a specific point of view or put its passions on its sleeve.” But that approach has also failed badly. Before Fine took over as managing editor, the publication was savaged for a botched story on rape culture at the University of Virginia. Appearing in 2014 and then retracted the following year, “A Rape on Campus” drew lawsuits against Rolling Stone that are still making their way through the courts.

Like many magazines, Rolling Stone and its ad revenue have shrunk, and it has increasingly turned to online content written by and for millennials. One political staff writer, Tessa Stuart, graduated from Cal with a rhetoric degree in 2009. She described the magazine’s political coverage as “self-aware” and noted that humor and irreverence were staples. One of her posts—“Anthony Scaramucci’s 10 Days in the White House, Ranked”—satirized the communications director’s short tenure along with the Internet’s preoccupation with listicles.

Fine noted that the HBO documentary, Rolling Stone: Stories from the Edge, includes footage of Wenner covering Mario Savio at the Greek Theatre. “That’s where the magazine comes from,” Wenner said. But he added that Rolling Stone’s perspective today shouldn’t be equated with Berkeley, in part because “the counterculture and its values spread across the country.” Perhaps more than any other publication, Rolling Stone was responsible for that development.

Rolling Stone’s Berkeley roots may lie deep, but they’re essential to its story.

Peter Richardson, Ph.D. ’91, teaches at San Francisco State University and has written critically acclaimed books on the Grateful Dead and Ramparts magazine. His work has appeared in a variety of outlets, from Mother Jones to The American Conservative.