IN THE SUMMER OF 1984 the senior scientists of Cetus Corp., a Berkeley biotech company, found themselves in a bind. One of their employees, a promising young scientist named Kary Mullis, had dreamed up a technique to exponentially replicate tiny scraps of DNA. He called it polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and if it worked it would change the world and likely earn Cetus a mountain of money. The only problem was Mullis was an interpersonal wrecking ball.

He fought with his bosses. He fought with his coworkers. He fought with Cetus security guards and receptionists. Though married, he dated his labmates—and fought with them, too. Behind Mullis’s bellicosity seemed to be an abiding certainty that he was brilliant and everyone else was a fool, hell-bent on undermining his work. Cetus management was left wondering: What do we do with this guy?

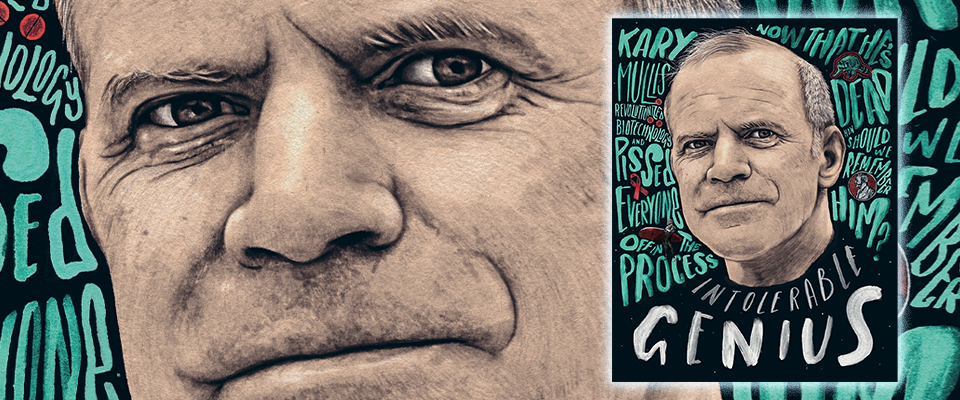

PCR ultimately did change the world, and Mullis joined the ranks of UC Berkeley’s 53 Nobel Prize winners. The laureate died in August 2019 at age 74 from complications of pneumonia.

A slew of obituaries have deftly danced around Mullis’s thornier personal attributes, but perhaps enough time has now passed that we can confront a question not unlike the one Cetus management did back in 1984: How should we remember this guy?

HAD THINGS GONE A LITTLE DIFFERENTLY, PCR might have remained a glimmer in its inventor’s eye. Luckily for Mullis—and probably the rest of us—he had an advocate.

Years earlier as a doctoral student in biochemistry at Berkeley, Mullis grew close with a younger classmate named Tom White after helping to repair a broken valve on White’s broken-down VW bug.

“I said, if you hire this guy Mullis, he’s an excellent synthetic chemist. I knew he was a good chemist because he’d been synthesizing hallucinogenic drugs at Berkeley.”

“[Mullis] ordained me as a Universal Life minister,” White says. “And I performed the wedding ceremony for his second wife in the hippie days on campus.”

Mullis was notorious at Berkeley for his irreverent approach to science and his skill in synthesizing psychedelic drugs. His curiosity ranged far beyond chemistry. At 22, he sent off an article to the prestigious journal Nature describing, in his words, “the entire universe from beginning to end.”

“I had read a lot about astrophysics and had taken some psychoactive drugs, which enhanced my perceived understanding of the cosmos,” Mullis recalled in his memoir, Dancing Naked in the Mind Field. The article was entitled “The Cosmological Significance of Time Reversal.” Incredibly, Nature published it. Not bad for a grad student in biology.

When the time came for his oral exams, Mullis was unprepared. White recalls, “He didn’t get his propositions right. He didn’t know general biochemistry.” Mullis himself believed that it was the Nature article that greased the wheels with the committee. Similarly, his thesis was so eccentric that the dissertation committee initially refused to sign off on it. According to White, several of his close friends edited his drafts in an attempt to “cut all the whacko stuff out of it.” Still, the final version retained its peculiarity.

“The deep mysteries of the cosmos are at last within our grasp,” Mullis wrote in the conclusion. “The question we must ask ourselves is whether or not we should go further. Perhaps there are organisms with other iron binding agents on other planets. Nuclear magnetic resonance is waiting. Will they escape the prying fingers and prurient eyes of the two-legged mammal?”

In his memoir, Mullis recalled weaving along the darkened road thinking to himself that the idea would make him famous, that he’d win the Nobel Prize.

After much lobbying by Mullis’s advisor, the committee signed off.

After graduating, Mullis moved to Kansas with wife number two, divorced, met future wife number three, then returned to Berkeley. While managing a café owned by his first wife, he bumped into his old friend Tom White, now a postdoc at UCSF Medical Center. White got Mullis a lab job at UCSF. Soon after, White was hired as a research scientist at Cetus Corp. And once again he went to bat for Mullis.

“I said, if you hire this guy Mullis, he’s an excellent synthetic chemist,” White says. “I knew he was a good chemist because he’d been synthesizing hallucinogenic drugs at Berkeley.”

Despite knowing little about molecular biology, Mullis was hired to work in the company’s DNA synthesis lab where he was tasked with streamlining the production of oligonucleotides, little molecules used to isolate sections of natural DNA for study. Thanks to his ingenuity, oligonucleotide production boomed. When White was promoted to director of molecular and biological research, he made Mullis head of the DNA synthesis lab.

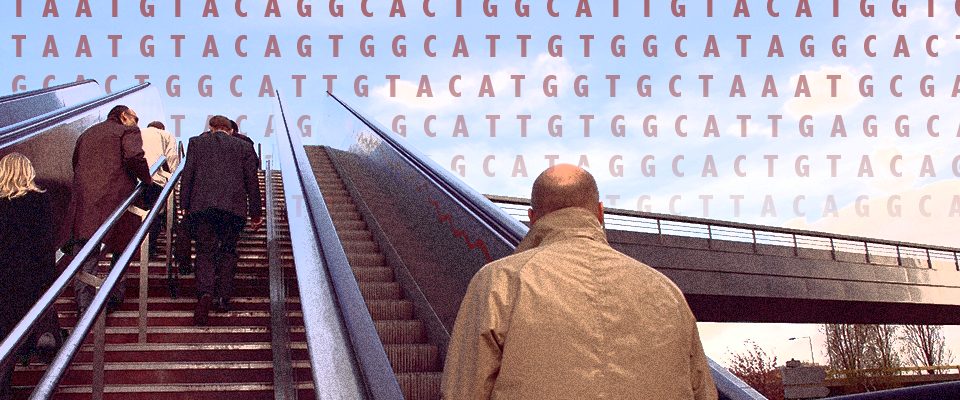

One of the main projects at Cetus was the quest to create a general diagnostic DNA test for disease. Cetus scientists had developed a method to isolate tiny fragments of DNA and test them for relevant mutations. The problem was that the target fragments were in such minuscule quantities, and the samples so cluttered up with other bits of DNA, that the test results were weak and ambiguous.

Mullis was not part of the DNA diagnostic team (he wasn’t exactly qualified), but as usual his hyperactive mind wandered. “[Cetus management] said 10 percent of your time you should do whatever you want to do,” Mullis later said in an interview. “I said, it’s hard for them to measure what 10 percent of my time is. So I can use as much of my time as I want to for my own curiosity.” One of those curiosities was the challenge facing the DNA diagnostic team.

Identifying these target DNA fragments, Mullis later wrote, was “like reading a particular license plate out on Interstate 5 at night from the moon.” Taking his metaphor further, Cetus scientists had a powerful enough telescope to read license plates, but they struggled to differentiate the target car from all the others on the highway.

“He really didn’t know much of anything about molecular biology. And so when he tried to tell all the molecular biologists that this was a good idea, most of them were very skeptical.”

Fittingly, Mullis’s epiphany came in his car, while driving through the hills of Mendocino County. He reasoned that by attaching two oligonucleotides to a split strand of DNA, he could isolate a desired section, such as the segment of DNA that determines sickle cell anemia. By adding polymerase, a natural enzyme required for DNA replication, he could create two identical copies of the fragment. His next thought hit him like a revelation: If he simply repeated this process, each repetition would double the target fragment, creating an exponential explosion of the target DNA, and weeding out the unwanted segments. In essence, Cetus scientists would now have a traffic jam to examine through their telescope. And crucially, every car would have the same license plate.

In his memoir, Mullis recalled weaving along the darkened road thinking to himself that the idea would make him famous, that he’d win the Nobel Prize.

He named it polymerase chain reaction and eagerly reported his bombshell idea to other scientists at Cetus. They weren’t impressed. It wasn’t the first supposedly “revolutionary” idea Mullis had touted.

“He really didn’t know much of anything about molecular biology,” White says. “And so when he tried to tell all the molecular biologists that this was a good idea, most of them were very skeptical. Scientists are always skeptical.”

To Mullis the skepticism was an affront. After a number of failed experiments, he got results that he believed suggested PCR worked. But Mullis had never been a thorough experimentalist, and these attempts to prove his concept lacked appropriate controls and repetition. The skeptics remained skeptical.

Mullis’s erratic behavior at Cetus wasn’t helping him bring anyone over to his side. A company party had to be shut down early after Mullis nearly came to blows with another scientist. He’d also begun dating a coworker in his lab, and the two engaged in public lovers’ quarrels. In one incident, he became jealous about romantic interactions between two labmates and threatened to bring a gun to work.

“It definitely put me in a tough spot,” White says. “His behavior was so outrageous that the other scientists thought that the only reason I didn’t fire him outright was that he was a friend of mine.”

Mullis held an eternal grudge. He felt he’d been ripped off, that White, Erlich, Randall Saiki, and others sought credit for what should be solely his. He called them vultures.

Instead, White decided to give Mullis a final shot to prove whether PCR worked. He removed him as head of the DNA synthesis lab and told him to work full time on proving his idea. “I knew Mullis was such a determined, obsessive personality that he would work on it in a phenomenally crazed sort of way to try to get it to work no matter what,” White says. Shrewdly, White assigned a separate group of top-notch experimentalists to work on the project in parallel.

Over the next several months, while Mullis continued to produce ambiguous results, the second group led by Henry Erlich and Norman Arnheim hit the jackpot. Mullis had been right all along. PCR worked.

The technique was a scientific turning point. Within just a few years, use of PCR exploded, fueling the expansion of the biotech industry. Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology David Bilder, says, “PCR revolutionized everything. It really superpowered molecular biology—which then transformed other fields, even distant ones like ecology and evolution. … It’s impossible to overstate PCR’s impact. The ability to generate as much DNA of a specific sequence as you want, starting from a few simple chemicals and some temperature changes—it’s just magical.”

In 1986, Mullis quit his job at Cetus. Before he left, management awarded him a $10,000 bonus for his idea, but the rights to PCR belonged to the company. Years later, Cetus would sell those rights for $300 million. Mullis held an eternal grudge. He felt he’d been ripped off, that White, Erlich, Randall Saiki, and others sought credit for what should be solely his. He called them vultures.

He moved to La Jolla, took up surfing, and largely turned his back on science. But science wasn’t quite done with him. On October 13, 1993, Mullis got a call at 6:15 a.m. from Sweden. “Congratulations, Dr. Mullis,” the voice said. “I am pleased to be able to announce to you that you have been awarded the Nobel Prize.”

“I’ll take it!” Mullis replied.

IF YOU WERE ONE OF THE TENS OF MILLIONS of Americans who tuned in to the O.J. Simpson trial in March of 1995, you may have caught a glimpse of Mullis sitting in the gallery. He’d been hired as an expert witness by O.J.’s defense to cast doubt on the prosecution’s DNA evidence. Normally having a Nobel Prize–winning scientist on your team would be an ace in the hole, but Mullis was more like the joker in the deck.

He’d become a vociferous critic of widely accepted scientific ideas, ridiculing the notions that CFCs caused the ozone hole, that humans caused climate change, and that HIV caused AIDS. Mainstream scientists were corrupt, he claimed, attracting funding for their research by spreading paranoia.

“Scientists could be something to entertain us and invent nice things for us,” Mullis wrote. “They don’t have to be justifying their existence by scaring us out of our wits.”

Ironically, Mullis also questioned the very DNA analysis made possible by his invention of PCR—thus, the Simpson legal team’s interest in his services. Trouble came when the prosecution made clear their plan to undermine Mullis’s credibility by citing his contrarian scientific views and his drug use (he still dabbled in LSD). Deputy D.A. Rockne Harmon asked the court for assurances that Mullis wouldn’t be high on acid while testifying.

In the end, the defense chose not to risk putting their Nobel witness on the stand, and it was probably for the best. Mullis wrote that if they had, he planned to take revenge on Harmon by accusing him in front of the jury—and the world—of an entirely concocted incident involving two young boys in a park. “I think LSD would have paled beside fictitious young boys,” he wrote.

If the O.J. Simpson chapter of Mullis’s post-Nobel life was odd, it was only in keeping with the rest of it. He’d largely given up professional science and, along with surfing, had taken up roller-skating, playing the guitar, and studying astrology. He cofounded a company called StarGene, which planned to sell jewelry with the DNA of dead celebrities embedded inside. “I’m not a ‘serious’ genius like Einstein,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “I’m a more playful kind of genius.”

Not everyone saw the fun.

In 1994, Mullis was invited to speak about PCR at the annual scientific meeting of the European Society for Clinical Investigation. Instead, he took the opportunity to impugn the science behind AIDS medicine. The chairman of the organization later described Mullis’s performance in a blistering letter published in Nature: “His talk was in style rambling and in content inappropriate for a public appearance of a leader of science. … His only slides (on what he called his “art”) were photographs he’d taken of naked women with colored lights projected onto their bodies.” His discussion of AIDS was “incoherent and insubstantial.”

Professor Randy Schekman compares him to the man in the White House. “He’s the molecular biology equivalent of Donald Trump in terms of his personal behavior.”

His views on AIDS didn’t just look bad, they may have had deadly consequences. By the late 1990s, South Africa was in the midst of a catastrophic AIDS epidemic. President Thabo Mbeki, under the spell of AIDS denialists including Mullis, declared that AIDS was caused by poverty, not HIV. Many South Africans were denied access to treatment. A 2008 study published in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes estimated that as a result, 35,000 babies were born with HIV and 330,000 South Africans died of AIDS unnecessarily.

“I’ll never forgive him for that,” White says.

It’s not unusual for Nobel laureates to use their newfound fame to advocate for their pet causes. Berkeley professor of cell biology Randy Schekman won the Nobel in 2013 and used his new pulpit to give lectures and write op-eds promoting basic research, public higher education, and open source journals. What is unusual is for a laureate to use their Nobel to cast aspersions on other scientists and the institutions that nurtured their career.

When Mullis won the Nobel, Schekman made a bet with one of the other laureates that year that Mullis would be the only American Nobel Prize winner to never be elected to the National Academy of Sciences. “I can collect on that bet now,” he says. “Mullis wouldn’t qualify because he didn’t publish enough independent papers to even be considered.”

Schekman, who calls Mullis’s Nobel a “complete fluke,” compares him to the man in the White House. “He’s the molecular biology equivalent of Donald Trump in terms of his personal behavior,” he says.

The Nobel Prize brought Mullis an avalanche of media attention, as reporters around the world scrambled for an interview with the madcap scientist. Most of the resulting profiles described Mullis as a whimsical, charming storyteller, enjoying what he called his “vacation life.” But Emily Yoffe, a reporter sent by Esquire to interview him in person in La Jolla, painted a different picture. She described a boorish egotist with a reckless streak. “Mullis does not have conversations,” she wrote, “he holds forth, spewing opinions like a whale clearing its blowhole.” She noted that his fridge was covered in pictures of partially clad women he’d dated. At some point during their interview in his apartment, Mullis grabbed her by the neck and tried to forcibly kiss her. She rebuffed him. But he tried again. And again. He asked her, “How can you say you know me without sleeping with me?”

“Kary was so persistent and so outrageous and got so nasty toward the end as he got more and more drunk,” Yoffe told me. Typically for such a major profile, she’d plan on conducting several interviews with the subject. Not this one. “I thought, I’m definitely not going to be in a room with him again.”

In Esquire Yoffe wrote that “… genius and gentility don’t always share the same chromosome.”

ONE NIGHT IN 1985, as Mullis took a stroll on his property in Mendocino County, he encountered a glowing raccoon.

“Good evening, doctor,” the raccoon said.

The next thing Mullis remembered he was walking along a nearby road in the light of morning, a time gap he attributed to alien abduction. He detailed the encounter in his memoir, Dancing Naked in the Mind Field.

“Mullis had a great idea, which he followed up with years of misrepresentation and self-promotion.”

In the book, Mullis also tells his version of the invention of PCR. It’s the story of a lone genius who, when he wasn’t chasing women across the astral plane, did battle against corporate overlords and petty, officious managers to bring polymerase chain reaction to the world. It’s an appealing tale, one Mullis actively cultivated, says Berkeley anthropologist Paul Rabinow.

“The public wants to see individual geniuses and maybe there are such things, I don’t know,” he says. “[Mullis] realized that this was the kind of story that sold and that people would write stories about.”

In his own book, Making PCR, an ethnographic history of the development of PCR, Rabinow gives a more nuanced and thorough account.

“The pursuit of … scientific truth is not an individual game,” Rabinow says. “It takes multiple different contributions … to make something like this happen. And it’s not to take any credit away from Mullis. It’s just that’s not what science is.”

Rabinow asked Erlich and Saiki, two scientists whose experimental rigor made PCR possible, how they felt about Mullis winning the Nobel. “I feel bad that I couldn’t feel better about it,” Saiki said. “Kary has his good points and bad points; the point is that we worked together.” Erlich said, “Mullis had a great idea, which he followed up with years of misrepresentation and self-promotion. Rewriting history was more productive than writing papers.”

Maybe the best way to remember Mullis and his invention of PCR is to make some space for the others who made it a reality.

Coby McDonald is a frequent contributor to California.

From the Winter 2019 issue of California.