This summer, Christie Poitra ’07, Ph.D. spent a few days talking about video game development and STEM at the Indigenous Youth Empowerment Program (IYEP) Summer Enrichment Camp in Lansing, Michigan. A collaboration between Michigan State University (MSU) and several other agencies, IYEP summer campers learn about citizenship and, among other topics, how to use games for STEM education.

Poitra’s hometown—Old Station, California, population 50—had nothing of the sort. “We had a gas station,” she says. “The nearest grocery store was 45 minutes away.”

Poitra overcame this dearth of opportunity to not only become the first in her family to graduate college, but an academic with a Ph.D. in educational policy from MSU. She now devotes her career to furthering education for indigenous K-12 students.

Poitra serves as the assistant director of MSU’s Native American Institute, where she is part of the American Indian & Indigenous Studies faculty and an MSU Distinguished Fellow. A little more than a decade ago, however, she almost gave up her higher education dreams. I’ll never get in to Cal. Why bother applying, she thought. A career counselor helped change her mind.

Swimming Upstream

Since her early teens, Poitra wanted to attend college, even though she didn’t really know what that meant. No one she knew had a college degree.

Like many families, Christie’s parents did not have the resources to pay for college. She is Latinx, Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa (descendant). She is also a first-generation college graduate—which added to her feelings of treading in unfamiliar water during her time at UC Berkeley.

“When you’re first-gen, you don’t know what to expect and you don’t know what to think,” she says. “You’re figuring out how to make your way against the current.”

Statistics didn’t favor her either. About 72 percent of Native American students graduate high school, compared to 84.1 percent for all students according to Department of Education data—the lowest of all ethnicities. Only 13 percent hold a college degree compared to about 28 percent of the total US adult population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

These barriers didn’t deter Poitra. She funded two years at Shasta College, a community college in Redding, California, with a combination of federal student aid and money earned from three jobs: an administrative assistant at an environmental engineering company, a Shasta College athletic department job and nights at McDonald’s.

In between shifts, she excelled in her studies. She became a Phi Theta Kappa member and officer. In the middle of one of its fundraisers, she learned she got accepted to Cal.

“It was a casino fundraiser night,” she recalls. “It was Wild West themed, so I was in this ridiculous saloon owner costume. I had to run all the way across campus to check the career center computer. The website froze! Finally, row by row, the page loaded, and I read, ‘Congratulations.’ I lost it.”

Mascara streaming down her tear-streaked face, Poitra ran back to casino night, where she got to tell her parents, professors and friends the good news. “My parents hugged me, they cried, they were so excited,” she says.

Finding Her Life’s Work: Education Equity

Poitra received The Achievement Award Program (TAAP) scholarship, which provides high-achieving, community-minded students from low-income backgrounds significant funding to attend Cal. The scholarship currently awards incoming freshmen and junior transfer students $6,000 per year and a laptop.

As a new legal studies major, Poitra certainly had credentials on par or above her peers, but she still felt out of place. She knew nothing about Cal and had never set foot in Berkeley. She picked Cal because a well-dressed recruiter visited her high school.

“I felt so intimidated because everyone seemed like the top of their class,” she says, recalling her first day at CalSO (now Golden Bear Orientation). “I was both happy and scared. I felt like I didn’t belong at all.”

Soon, Poitra found the Indigenous and Native Coalition Recruitment and Retention Center (INC-RRC), which held multiple events for incoming freshmen. She formed friendships that continue today.

“They are all practitioners in the tribal context, amazing academics, amazing activists and incredible people,” she says. “They pushed me to think about things differently and think about myself differently.”

Much like Poitra, today’s Native students have to adjust to life on a large campus in a new city. And because Native American and Alaska Native students make up less than one percent of the student population (.4% in Fall 2017), they can feel invisible. Classroom conversations, which discuss Natives only in historical context, add to the isolation.

INC-RRC works to bring members of this small community together. Soon, graduates can also join the Native and Indigenous Alumni Chapter, chartered this year.

Phenocia Bauerle, director of the Native American Student Development office, and three other alums formed the organization out of a strong need for alumni social and networking opportunities. “I’m in touch with some graduates, but the alumni are siloed,” she says. “There was no centralized anything. Our community is so small. When you get into the national job market, it’s especially important to see and meet other successful alumni.”

During her time at Cal, Poitra participated in several groups outside of INC-RCC. She served as TAAP student council president, received a Cal Alumni Association Leadership Award, and participated in the Ronald E. McNair Post-Baccalaureate Program.

“She was resilient and steady,” recalls Harold H. Campbell Ph.D., director of UC Berkeley’s McNair Scholars program from 2000 until 2016. “She’s a proud member of a tradition as well as an academic. She has a quiet spirit that draws people to her.”

As a McNair scholar, Poitra researched tribal sovereignty in Northern California. She still had her mind set on practicing law, but the idea of research spoke to her.

Upon graduation, Poitra entered a teaching program on the Navajo Nation in New Mexico, where her purpose became clear. The program hired Poitra to teach first-grade math, but the curriculum required specific shapes, coins and other implements. “Without the teacher implements, the curriculum was useless,” she says. The implements never arrived.

Later, Poitra learned a teacher at a more affluent school in Gallup, New Mexico, had received the implements right on time. Poitra’s students learned necessary skills with the help of implements Poitra made herself.

“That was the moment I committed to education equity,” she says. “I couldn’t let that go. I was teaching in a classroom where nearly all my students were on free and reduced lunches and to have that kind of inequity in the district made me really angry.”

She earned her M.A. in Native American studies from UCLA. MSU then offered Poitra a full-ride scholarship to pursue her Ph.D. She immediately focused on how tribal governments develop education programming to support their youth. For her dissertation, on the political process of educational policy development among tribal governments, she worked with two tribes in California.

“I learned a lot about how tribes make difficult education decisions,” she says. “When I talked to tribal government officials, education meant possibly college, but it also meant being a good person, learning your language and learning your culture. That affects what policies they pursue.”

“…there’s no one image of what it means to be Native, and what it means to be a tribe.”

Through her work at MSU’s Native American Institute, Poitra works both in the academic setting and in communities to learn about and further education, agriculture, mental health issues, and even anti-counterfeiting measures for Native American art.

“It’s all really exciting, but all really complex work, because there’s no one image of what it means to be Native, and what it means to be a tribe,” she says. Indeed.

According to the National Conference of State Legislature, there are 573 federally recognized tribes. Each nation has its own government and many times, its own court system, police force, and school system.

“Sometimes Western society views Native people as this big group, and really, it’s a huge collection of tribes each with incredibly different values,” Poitra says.

Poitra’s current role at IYEP’s summer camp ties loosely to another, much more rural project. In July, she accompanied American Association for the Advancement of Science, Science and Technology Policy Fellow Dr. Wendy Smythe to a remote Alaskan village to work with an Alaska Native community. Dr. Poitra provides an education perspective for Smythe’s work to increase Alaska Native participation in STEM disciplines.

During their last trip, Smythe, Poitra, and a team of graduate students collaborated with a school district to support K-12 STEM learning through the creation of tribally centered STEM curriculum. While recording footage for curriculum videos, they encountered an angry mother bear.

“My job is always interesting!” she says. “No two projects are ever the same.”

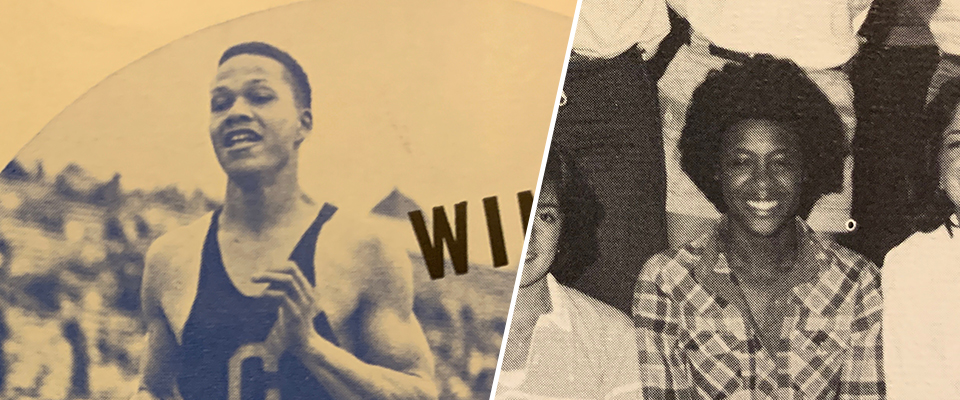

Photo credits: (top) Jackie Keliiaa; courtesy of Christie Poitra