A turn through the land of the Moors.

Outside our windows the desert is silent, malevolently hot, and virtually empty. Every so often, though, we see things: knots of camels grazing the scrubland; hulks of cars left for dead by the roadside, their skeletons filling with sand; wraithlike men engaged in the Sisyphean task of sweeping the blowing sands off the blacktop.

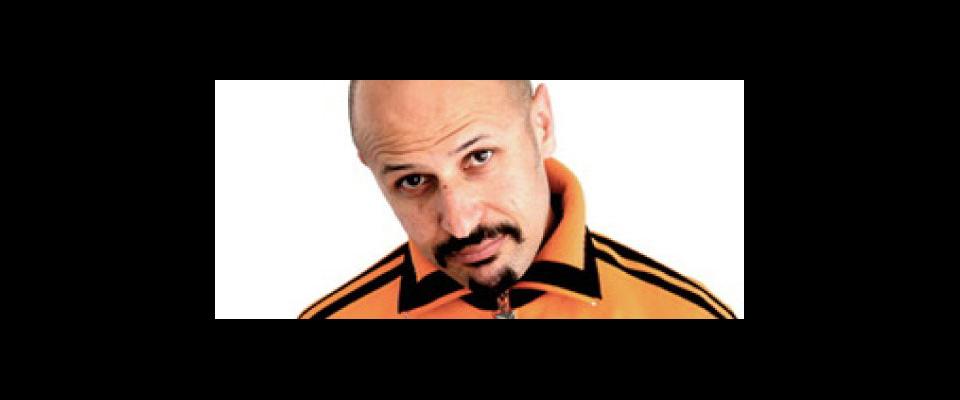

The man driving the Land Cruiser has seen it all before. Our guide is a whippetlike man of indeterminate age. His face is deeply lined; a meticulously cared for goatee frames his mouth. Like everyone else we’ve met in Mauritania, Sidi Al Moktar is taciturn to the point of caricature. He is a font of knowledge about camels—how long they can go without drinking, how far they can walk without resting. About almost everything else, he’s mum.

With the sun directly overhead and the Freon flagging, we ask if we’ll be stopping to eat lunch somewhere. Never taking his eyes off the road or his hands from their fixed positions on the wheel, Sidi Al Moktar considers the question. Then: “Peut-être.” Maybe.

Riding the line between Arab North Africa and black sub-Saharan Africa, Mauritania is three-quarters sand and, thanks to creeping desertification, growing more desiccated by the day. This is the land of the Moors, Africanized descendants of the Arabs who once ruled Spain, a nomadic and arch-conservative people who appear, by and large, indifferent to the outside world. Nouakchott, the tumbledown, monochromatically beige capital city, perches almost, but not quite, on the Atlantic. Shunning the coastal breezes, it faces east, toward Mecca and the Sahara.

Mauritania has always been something of a backwater. During colonial times, it was an open-air prison into which the French authorities dumped their most troublesome political opponents. That reputation hasn’t improved much since the country gained independence in 1960. “Why in the world would you go to Mauritania?” asked an acquaintance who had worked in the country. “How do you feel about diarrhea, sunburn, and fine-grain sand stuck in all crevices?” she demanded, only half joking.

Most of the people who visit Mauritania are French and of the crystals-and-eco-sandals set. They see in the dunes an African Sedona, a place of mystical healing. (“The desert has such power,” I hear a ponytailed man in a shapeless, multi-colored shirt rave to his partner in an Internet café one day.) Many of these visitors arrive by charter, flying straight from Paris to the interior, a town called Atar that is the gateway to the Sahara. By contrast, we’re traveling overland and are regularly stopped, our itinerary questioned, and our passports examined by deeply skeptical men in epaulets and mirrored sunglasses. A minor nuisance next to the realities of everyday life here.

For the vast majority of Mauritanians, life is distinctly Hobbesian—40 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, and there are few good jobs, health clinics, or even paved roads. Slavery, though officially outlawed, is still a fact of life, a legacy of centuries of Moorish mistreatment of the country’s black African minority.

And it’s all the sadder because Mauritania, as Sidi Al Moktar proudly tells us, is rich in so many ways. Oil has been found in the deep, cold trenches offshore; the low hills of the interior, meanwhile, are stocked with gold, iron, copper; the teeming waters off the Banc d’Arguin swarm with trawlers from Europe and Asia. One afternoon in Nouakchott, as we pass high-end homes rising from the rocky dirt, our man begins to rail against the government. “They build villas here and vacation in France, and the people have nothing!” he spits. This is the only display of emotion we’ll ever see from Sidi Al Moktar, and it hints at a life we can only imagine. He deflects all inquiries about his family, where he lives, how long he has been a driver. When we leave our auberge one morning, we find him still asleep in the car, curled up in the backseat; he had told us that his accommodations were already taken care of.

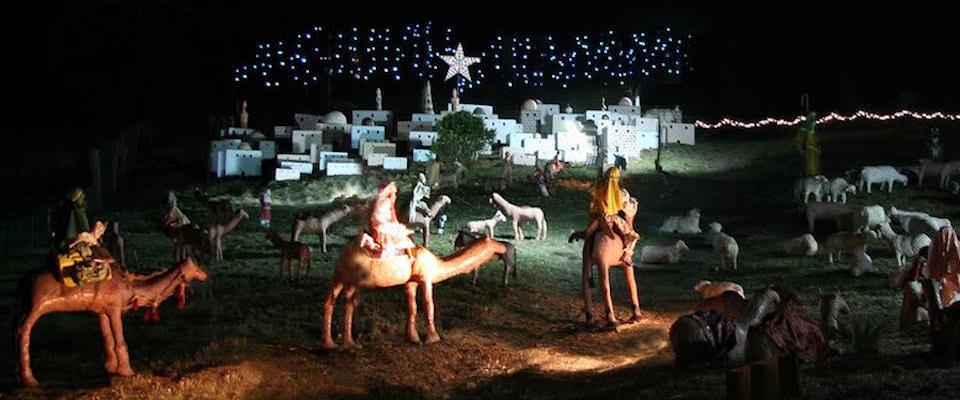

After a few days of travel, we arrive in Chinguetti, an old salt-and-spice caravan town so far off the track that its only power comes from generators. At the entrance to town, a pair of forlorn rock posts stand sentinel against the surrounding desert. “Bienvenue à Chinguetti,” reads a sign. We pose for pictures, wincing from the heat. Like the country itself, this town is slowly losing its battle with the desert, the dunes filling the narrow streets, burying its buildings. Chinguetti is Islam’s seventh-holiest site, alongside more famous places like the Kaaba in Mecca and Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock, and was once a bustling medieval university town filled with mosques and madrassas. It’s hard to see any of that now, though: The town feels orphaned, dying despite its status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

We visit one of the town’s libraries, housed in a tiny mud-brick building near the 16th-century stone mosque. Ducking our heads, we follow the caretaker, an ascetic, cadaverous-looking man, into a musty room. It is cool inside, and dark; the sagging wooden shelves hold stacks of centuries-old Islamic manuscripts, unprotected, flaking away and half-devoured by time and bugs. Amazingly, the caretaker lets me handle these invaluable texts.

My girlfriend isn’t allowed anywhere near the Koran, he declares, but she might be able to touch some of the other manuscripts— provided she isn’t “unclean” (menstruating). She tries to kid him about this: “Really? So what if I told you I wasn’t menstruating, but I really was?”

“God would know,” he replies, unsmiling.

Pulling out a Koran that looks like it must have been written entirely in gold leaf, the caretaker reads part of a sura for us. His voice is smooth and low, his intonation precise, each word thudding to a stop in the room’s close air. “Truly, God is forgiving and merciful,” he says in classical Arabic.

Back in Atar, we eat by candlelight at a grottolike cafe with dusty tables on a patio strung with tiny lights. It’s run by an elderly Frenchwoman who spends most of her time dressing-down her helper, a hangdog young guy who can’t seem to set the tables to her satisfaction. Even though we are deep in the desert, fish cakes are the only item on the menu.

Beyond the main streets Atar is pitchblack at night, and we get lost on the way home, stumbling through dirt lots strewn with castoff rebar and old tires. Turning a corner, we come upon a market stall in the middle of nowhere, a storefront brightly lit by long fluorescent tubes. As far as I can tell, it’s the only illumination for blocks. A teenager stands behind the counter, leaning into a textbook, but looks up when we approach. He shyly tries out a greeting. In turn, I offer up a “good evening” in Arabic. Settling into French, the three of us pass the time. We learn that he has grown up not far from here, that he wants to be an engineer, that he would like to travel. He asks us about our homes in America, about life in California. “It’s cold sometimes because we live by the sea,” we answer. He has never seen the ocean and is surprised to hear that California isn’t always warm. He seems glad of our company; we are glad of his. Only later do I realize how exceptional this unguarded exchange is.

At the auberge, I join Sidi Al Moktar and a group of men in front of a TV they’ve dragged into the courtyard. They don’t invite me to sit down with them, but neither do they turn me away. In fact, they appear utterly indifferent to my presence. In silence, we watch Al Jazeera under the stars.