Seeking Mayan ruins, a reporter instead stumbles into America’s drug war.

I knew we were in trouble as soon as our minivan crested the hill at 8 a.m., about 30 miles south of Guatemala’s border with Mexico. A band of heavily armed men suddenly erupted from the jungle, taking positions in the center of the road. Cloth bags with eye holes masked their faces.

The cowled gunmen surrounded us, screaming orders in a local dialect, their weapons trained through the van’s windows at our heads. In response, the driver turned up a narrow dirt path into the dense jungle.

What happened over the next few hours was a primer in the tortured relations between North and South. But at the time, geopolitical analysis was the furthest thing from my mind. Only the second-by-second chain of events seemed meaningful.

There were five foreigners in the van, en route to the ruins of Tikal, an ancient Mayan city. Sharon Silva, who attended Berkeley and later copyedited for the University of California Press, sat beside me. Our fellow passengers were an Irishwoman in her 30s and two young Israelis, both recently discharged from military service.

Riding next to the van’s driver was a solidly built man in perfectly creased chinos and a Ralph Lauren polo shirt. We had picked him up at the roadside in the nearby village of El Remate—an odd move for our chartered tourist vehicle. As the van climbed the hill, Polo Shirt tapped out messages on his cell phone. And he never spoke a word during the drama that soon unfolded. Later, these details would assume significance.

In its heyday 1,500 years ago, Tikal was the crown jewel of an extraordinary civilization, a 48-square-mile metropolis with more than 50,000 residents, landmarked by enormous limestone temples and pyramids. Today most of them, along with hundreds of other lost Mayan sites, are hidden under a vast blanket of tropical rainforest.

From an archaeologist’s perspective, Guatemala is among the richest countries on Earth. From every other perspective, it is hopelessly poor and staggeringly violent. According to the World Bank, more than half the population is below the poverty line and a quarter live on less than $1.25 a day. Eighty percent of its rural children reportedly suffer from malnutrition. The average citizen has just five years of schooling.

In 2010, only a handful of the world’s countries registered more than 40 homicides per 100,000 people. Guatemala is one of them; neighboring Honduras and El Salvador are two of the others. By comparison, the United States averages around 5 per 100,000 each year.

Behind this homicidal nightmare lies a 3,000-mile chain of narcotics supply and demand, anchored by pitiless Colombian and Mexican drug cartels on the one hand and the affluent U.S. market on the other. Central America’s remote jungle trails have become the principal transit route for an estimated 350 tons of cocaine shipped north annually by the cartels. Add in a burgeoning market in methamphetamines, and the total value of narcotics transported across Guatemala exceeds $100 billion, almost three times its entire legitimate GDP.

Petén, the northwestern province where our van was hijacked, is ground zero in the Central American nightmare. The tale of Petén’s descent into the abyss begins in Washington, D.C., more than two decades ago, when militarized security programs became the keystone of overseas drug policy under President Ronald Reagan. In the name of a no-holds-barred War on Drugs, the U.S. policy mandated hugely reinforced Navy and Coast Guard patrols aimed at interdicting cocaine shipments from South America via the Caribbean.

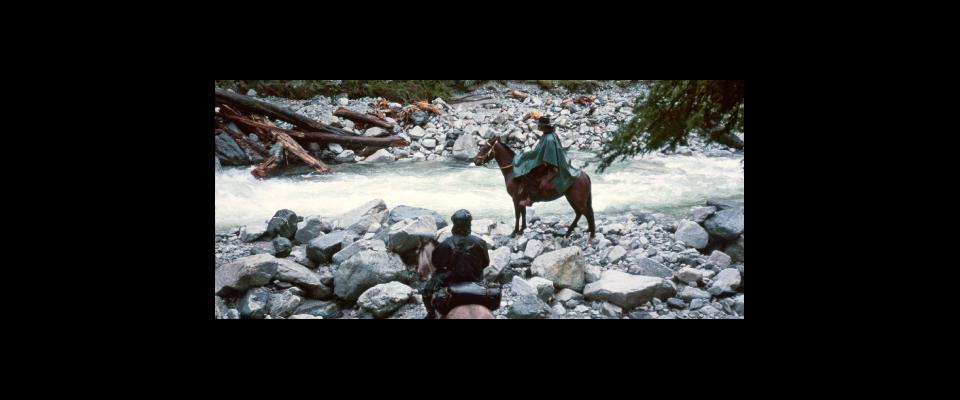

Within months, the cartels managed to shift most of their transport operations to land, bypassing the U.S. maritime blockade. Today small planes and boats ferry cocaine along the Pacific coast to isolated coves and remote airstrips in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala, across waters where U.S. interdiction efforts are all but impossible. From there, the drugs are carried over mule tracks to Petén, consolidated with the soaring output of meth (processed locally by the Mexican Zeta cartel), and sent north toward the Rio Grande.

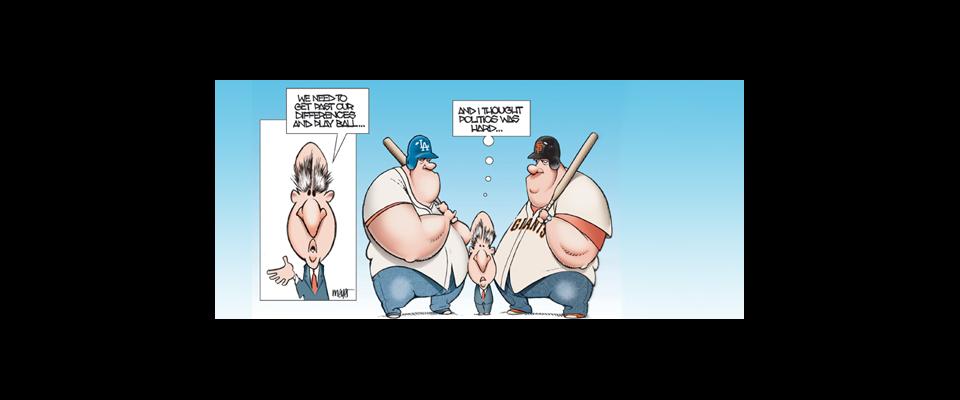

In combination with related U.S. domestic programs, according to figures acquired by the Associated Press under the Freedom of Information Act, the cumulative price tag for the War on Drugs since its inception exceeds $1 trillion. Put bluntly, the program has been a colossal failure, one of the most expensive and counterproductive government initiatives in U.S. history, “with devastating consequences for individuals and societies around the world.”

And that’s not the judgment of a small coterie of liberal critics. It comes from the Global Commission on Drug Policy, a high-level international body chaired by senior Republican luminary George P. Shultz, Secretary of State in the Reagan Administration, whose co-commissioners include former United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan and five presidents and prime ministers.

Despite the War’s immense cost, as noted by the commission’s 2011 report, cocaine use actually rose by 27 percent over the decade 1998–2008. It spawned a “huge criminal black market, financed by the risk-escalated profits of supplying international demand for illicit drugs,” according to Antonio Maria Costa, executive director of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

“The big guys in this market deal in large-scale capital,” says Professor Laura Enríquez, a UC Berkeley sociologist and leading authority on Central America. “They preside over significant economic enterprises that are multifaceted but lack ‘clarity’—businesses that are anything but above-board, where the competition that is part of any economic sector takes a violent turn.”

The big guys own palatial residences in Miami, Cali, and Acapulco. But they can’t manage without “little guys”: unemployed young men who are inured to a brutally murderous environment. The sort of young men who have made Central America one of the most dangerous places on the planet, and who waited for us in the jungle of Petén.

Like the strategy underlying the War on Drugs and the tax dollars that pay for it—like the consumer demand that nourishes the cartels—the back story of those young men is set in the United States.

With the gunmen walking alongside, our van was slowly driven deeper and deeper into the jungle. The Israeli vets worried me. They had been through combat duty in Lebanon and on the West Bank. “No heroics,” I said to them as the tension mounted. I needn’t have bothered. Veterans or not, their faces were ashen. No doubt mine was, too.

We slogged through a series of mud holes until the wheels sank in up to their axles. Three or four of the men took up positions around the stranded vehicle while another boarded, swinging a machete. He barked out a dialect command that needed no translation. We reached for our wallets, handed him our money.

He jumped out of the van, crammed the cash into a bag, and spoke with the rest of the gang. They seemed to be arguing about the next step. About what to do with us.

Machete turned, climbed back into the van, and went straight for the Irishwoman. He held his blade at her throat with his right hand and began pawing at her with his left, searching around her waist and between her thighs for a hidden money belt. He grabbed her purse, found an iPhone and a Nikon inside, and threw the bag out the door to the others. Then he moved on to each of us in turn, taking everything: wallets, credit cards, identity documents, cameras, watches, rings, cell phones, backpacks.

No one offered any resistance—until he lunged at Sharon and grabbed a black shoulder bag lying next to her on the seat. “No!” she yelled, yanking it back. What only she and I knew was that the bag was actually mine. Her own bag was jammed up against the side of the van, where she held it tight with one leg as she struggled with him.

It was a conscious gambit on Sharon’s part, and he fell for it, convinced that the bag must be hers. Why else would she have fought for it with that blade a few inches from her jugular? He laughed out loud, contemptuously, when she finally let go after what seemed an eternity but probably consumed no more than a minute. I stood paralyzed in the aisle of the van just a few feet away, my eyes riveted on Machete’s right arm, agonizing over what to do. It was the longest minute of my life.

There is a charged intimacy to such moments, a heightened sensitivity to random detail. As Machete struggled with Sharon over the bag, I noticed the peculiar tattoos on his fingers, a carefully etched sequence of crosses, esoteric symbols, and numbers. I’d seen them before, many years earlier, working the police beat in San Jose. They were the cult signs of the maras.

The word mara, reputedly derived from the indigenous Caliche language, is shorthand for the fearful marabunta soldier ants of Central America, nomadic predators that wander the countryside in ferocious swarms searching for prey. But in its abbreviated form, mara also alludes to youth gangs that haunt the region’s cities and rural contraband trails. They are the necessary little guys in the drug trade: the couriers and guards of northbound drug shipments, the local shock troops in wars among the cartels, the moonlighting armed robbers on the rainforest highways.

The gangs’ institutional origins are not Central American. They are rooted in the barrios of Los Angeles, California, where mara emerged in the mid-1980s as the self-adopted tag of two widely feared crime bands: Mara Salvatrucha, otherwise known as MS-13 (the 13th Street gang), and Mara Calle Dieciocho (the 18th Street gang).

In Latin America, youth gang members are generally recruited before the age of 15, then graduate from shoplifting and petty drug-running to felonies that land them in state prisons. Sheer survival in the packed penal system depends on securing protectors, and for young Central American inmates, protection is almost exclusively available through career advancement in maras. “You go to prison and you become a ‘made man’ in a gang,” says Benjamin Lessing, M.A. ’06, M.A. ’09, a newly minted Berkeley Ph.D. in political science whose pioneering research on Latin American drug cartels has attracted international attention. “The state provides a service, a safe environment for training.”

There is no easy solution to this problem, he adds. “If you transfer convicts to a faraway prison, you risk spreading the gangs. They are fluid, resilient, with no single leader. Their members are deeply rooted in each mara’s culture and traditions.”

In California, troubled kids enter the cellblocks and hardened pros come out. The devastating twist is that until recently they were not released to the California streets unless they were native-born U.S. citizens. In keeping with a major judicial tenet of the War on Drugs, young immigrant convicts—many of whose parents had fled north from civil wars that wracked El Salvador and Guatemala into the 1990s—were deported by the thousands to Central America between 1995 and 2010.

They carried the culture and traditions of the maras with them, recruited their own followers in the slums of San Salvador and Guatemala City, and eventually signed on as enforcers for the cartels. By 2006, there were an estimated 14,000 mara gang-bangers in Guatemala alone, and according to a report by the U.S. Army’s Strategic Studies Institute, the homicide rate for that nation’s capital had surpassed 100. The worldwide average is 9.

A cell phone rang outside the van just as Machete was rifling my shoulder bag. Two more calls sounded in the next minute, and he abruptly turned away from us and rejoined his partners. They held a quick conference. Then they ran off, as suddenly as they had appeared, disappearing into the jungle depths with their booty. Something about those calls had spooked them. We waited until we were sure they were gone and then walked back to the road, leaving the immobilized van behind us in the mud. Hours crept by before half a dozen police cars roared up, apparently sent by a passing motorist.

When our depositions were taken at the El Remate police post, which faced the spot on the road where the polo-shirted man had boarded our van, we agreed on very little. One Israeli and the Irishwoman said there had been five men, three of them armed with rifles. The other Israeli insisted that everyone had a rifle. Sharon and I remembered four men, two with rifles and two with pistols. Our guesses at the distance we’d been dragged into the jungle ranged from 500 yards to a mile, and the time we’d been held captive from 15 minutes to more than an hour. Truth, under acute stress, is strictly personal.

But a fuller picture did take shape as our nerves settled. It struck me, in retrospect, that the driver and his silent passenger had sat passively in the front seat of the van throughout the ordeal, all but ignored by our abductors. Just a few minutes after we reached the highway on foot, a white SUV had driven up; Polo Shirt opened the door and got in. I asked in Spanish where they were going. “Tikal,” the man at the wheel said. On the theory that I’d be able to find help there, I asked if he would take me along. “No speak Español,” the SUV driver said in pidgin English. It seemed unlikely, but by then everything had taken on a surreal quality. The SUV pulled away.

As for Sharon’s trick, our fellow passengers felt it had been a stroke of genius. It saved her passport and a credit card, making it possible for us to buy a bus ticket back to Guatemala City and leave the country. In the immediate aftermath of the hijacking, we all shared her conclusion that the gang wouldn’t have hurt us, despite their machetes and guns. Shooting a foreigner would bring a crackdown, a setback for the robbery business. At least that’s what we wanted to believe.

A government lawyer from Flores, the closest city, soon deflated any such comforting illusions. He was openly surprised to hear that Sharon and the Irishwoman had not been raped. That was usually part of the experience, he said. Sexual humiliation was a staple element in the mara traditions.

When we returned to Guatemala City on an overnight bus, with two armed men posted at its door, we learned that an American had been shot in the head during a hold-up the day before, and another the day after.

Laura Enríquez, the Berkeley sociologist, has been studying rural Central America on the ground since the early 1980s, when she undertook what became an endless commute between North and South. As we sat in her office at Barrows Hall, Enríquez drew a concise portrait of the narcotic nightmare that has enveloped much of the Central American isthmus: the insatiable U.S. market for drugs; the arrival of the maras from California and their enlistment by “the big guys”; the terrible aftereffects of ideological conflicts in the 1980s and 1990s that “fundamentally tore apart the social fabric in places like the Guatemalan highlands.”

There is also “the sheer thoughtlessness factor,” she adds, referring not only to the backfired policies of the War on Drugs, but also to ill-devised economic aid programs designed by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. In the guise of structural reforms imposed from abroad, she says, “social services and formal employment—regulated jobs in things like factories—were cut back massively. People flowed from both the countryside and urban areas into a nonregulated ‘informal’ sector where life is catch-as-catch-can. If a drug trafficking job in that sector pays well, there is little evident alternative to it.”

But underlying the nightmare, Enríquez says, the net that ties everything together is the wholesale corruption of military and police agencies. “That’s what allows the traffickers to operate. That’s the real key.”

When the cartels shifted their operations from the Caribbean to the Central American land route, they conspicuously avoided Panama, which is closely monitored by international police services in the Canal Zone, and Nicaragua, which stands apart in Latin America for its professionalized, uncorrupted law enforcement bodies, according to Enríquez. Yet they have been largely ignored by the international funding agencies presumed to be searching for models that work. From 2009 to 2012, these countries were allocated a scant $110 million by USAID, the principal source of Washington’s financial assistance. The corresponding subsidies for Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador totaled $650 million.

In Guatemala alone, the annual USAID budget grew from $42 million in 2004 to nearly $100 million in 2010, the very years in which violence spun out of control. Honduras is the single most homicidal nation on earth today, with more than 80 murders annually per 100,000 people. A decade ago, before money poured in to combat narcotics trafficking, the murder count was just over 13. The 2010 rate in both Costa Rica and Nicaragua stands at around a dozen, one-eighth the toll in Honduras.

From these statistics, it is difficult not to conclude that the more money the North spends on the War on Drugs, the more it breeds trafficking, bloodshed, and the corruption that feeds them.

Listening to Laura Enríquez, I thought about the man in the polo shirt, who had boarded our van less than 200 yards from the El Remate police outpost, and the SUV that inexplicably materialized to pick him up as soon as we walked out of the jungle. I thought of a chart I’d seen on the wall of the outpost, listing Crimes Committed each month for the previous three years. It was all zeroes. The commanding officer had insisted it was accurate. “Things like this never happen in Petén,” he said of our abduction and robbery.

The lawyer from Flores shook his head when I told him about the blank crime chart, the mysterious passenger, and the white SUV—and the curious emptiness of the Tikal highway. The armed and hooded men had seized us in the middle of the road in full daylight, without the slightest apparent concern that another vehicle, much less a police car, might drive by.

“Let’s just say that these phenomena are not unrelated,” he commented. The transit company that owned our van had been suspected of organized crime connections for years, he said, and so had the local police. “The investigations never get anywhere. There are robberies and much worse things in Petén almost every day.”

That very morning, he added—around the time Machete’s cell phone rang and our abductors suddenly melted away into the jungle—29 people had been decapitated on a ranch a few miles east of the Tikal road. It was assumed that the murderers and their victims were members of rival cartels, but no one really knew for sure.