Nearly a year after the Rio Olympics, babies in the city’s favelas are still being born with microcephaly as a consequence of the Zika virus. The mosquito-borne disease has been identified by the World Health Organization as a congenital epidemic of international concern, yet one seldom hears about it in the international media. That’s a far cry from the lead-up to the Games, when a steady parade of Zika headlines sparked near-hysteria.

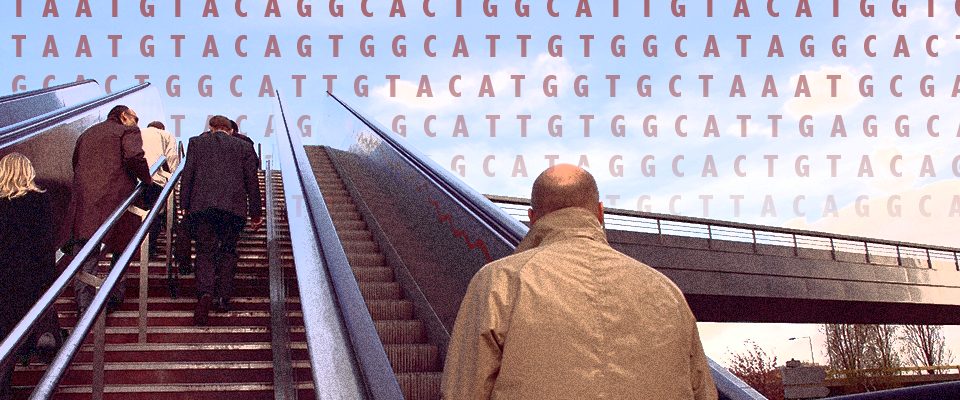

According to a piece published in March in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, by researchers from Berkeley’s School of Public Health and Brazil’s Universidade Federal Fluminense, athletes and spectators at the Olympics were never at much risk of contracting Zika. For one thing, the epidemic was already in a seasonal decline when the Games were held, as predicted by epidemiological models. For another, wrote the authors, “Zika is, and will continue to be, a disease of the urban poor.” In urban slums particularly, crowding combined with poor water and sanitation infrastructure “offer ample opportunities for mosquitoes to breed and spread the Zika virus.”

The authors observe that, in fact, no new cases of Zika were reported in connection with the Rio Olympics. The media-generated tourist scare, they argue, was “little more than demagoguery.”

Snyder feels the effect of misplaced media attention was to pull resources away from communities that most need help: the poor living in the world’s teeming megacities.

“I was really frustrated by what I saw as a lot of attention that was focused on these populations that weren’t really at risk,” said coauthor Robert Snyder, of Berkeley’s Center for Global Public Health.

As with earlier reports on Ebola outbreaks, Snyder feels the effect of misplaced media attention was to pull resources away from communities that most need help: the poor living in the world’s teeming megacities. “We really need to start thinking about the driving factors of these diseases, which are these large concentrations of urban poverty,” said Snyder.

Dr. Phuoc Le agrees with that assessment. A physician at UCSF Medical Center and assistant professor at Berkeley’s School of Public Health, Le worked on the front lines of the Ebola crisis. He says, “The industrialized world doesn’t want to think about the hundreds of billions of dollars required to tackle root causes of disease.” As such, he says, the response is “very reactionary rather than proactive.”

Meanwhile, Le added, the conditions in urban slums make a rich environment for viruses to incubate. One of these days, he predicts, “there will be a one-point mutation that allows it to become much, much more contagious.” If Ebola were to become as infectious as measles, Le says, we’d be in dire straits everywhere.

Says Snyder, “We’re just going to keep having these sorts of outbreaks until we acknowledge the real source is poverty and inequality.” These are two “very entrenched issues that fancy technological solutions don’t solve.”