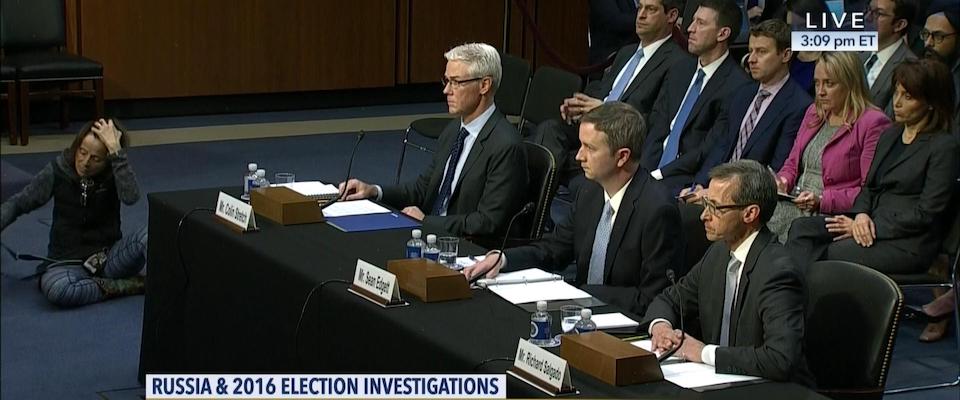

Representatives from three of Silicon Valley’s most powerful tech firms—Facebook, Google, and Twitter—trooped up to Capitol Hill last week and told senators they were really, really sorry the Russians hacked their platforms and may even have influenced the recent presidential election. But their contrition wasn’t followed by substantive plans to remedy the situation. Indeed, Colin Stretch, Facebook’s general counsel (Mark Zuckerberg was a no show), balked at Senator Al Franken’s (D-Minnesota) suggestion that the company spurn political ads purchased in foreign currencies.

There is a growing sense that Google, Facebook, and Twitter are operating beyond the norms that govern traditional media, eroding the rule of law and civic protections in the process. The Russian breaches are an inflection point, says UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism Dean Ed Wasserman—both for social media and the public.

“There’s no exaggerating how important this moment is to [social media’s] future,” says Wasserman. “We’re safely behind the Millennial euphoria over social media, and their challenge is to embrace a social mission and a civic role. These companies have benefited enormously from the conditions we are now deploring. But I do think they’re aware of that, and I think they ultimately won’t want to be on the wrong side of history, they don’t want a total mudslide on their consciences. They’re prospering in this terrible situation we’re in, but they also know how vulnerable they are and that their public reputations are in jeopardy.”

“Facebook’s business model requires you to keep clicking,” says Jaroslovsy. “Public embarrassment alone may not be enough to force them to make their platforms more restrictive. I’ve spent a lot of time covering the news in Washington, and I have a somewhat jaundiced view of these Kabuki dances like the one we saw last week. Hearing companies come to the Hill and admit, yes, we have a problem, we’re contrite. Then they work behind the scenes, lobbying and making donations, ensuring any regulations coming out of Congress are toothless and won’t affect their core business practices.”

Contributing to the problem is public complicity; as things now stand, most people like Facebook. Each person can find a cozy niche that suits her or him to a T – a “filter bubble,” observes Jaroslovsky.

“People naturally gravitate to material that appeals to preexisting biases even if it’s fake news,” he says. “Everyone retreats deeper and deeper into their echo chambers, and information becomes devalued. The bad drives out the good. The things that keep people tapping don’t have to be true. And again, as far as social media companies are concerned, it’s all about the tapping.”

So can the great super tanker of social media be turned around before it crashes on the rocks, taking the republic down with it? Maybe: but first the companies must be held accountable, says David Cohn, a senior director at Advance Digital in San Francisco and a former Ford Fellow at Cal’s Graduate School of Journalism.

“They can’t be allowed to throw their hands up in the air and say, ‘Oh, we’re not traditional media companies, we aren’t responsible, we can’t manage this stuff,’” says Cohn. “They need to do some serious reorganization. If a newspaper or TV broadcast station put out propaganda, heads would roll.”

Cohn says that “all code is political,” and the algorithms used by the social media giants are designed to result in predictable outcomes. Indeed, Facebook’s algorithms now indirectly control the way all news, at outlets ranging from PopSugar to the New York Times, is disseminated.

“This idea of a mythical algorithm that solves a given problem is only effective when no one has an incentive to game that algorithm. And as we’ve seen, there’s plenty of incentive to game any algorithm that pertains to news.”

“Facebook’s algorithms are designed so users can create personal identities, and the news outlets that rely on Facebook [to propagate their content] have adjusted their own editorial policies to conform to that,” says Cohn. “Now, that’s fine, laudable even, if you’re talking about your aunt’s wedding or your cute dog photos, but it’s not laudable when you’re talking about sharing critical civic information. So Facebook needs to redesign itself so its news products aren’t linked to personal identity.”

Indeed, says Cohn, Facebook is using several countries as a test bed for moving non-promoted news to its Explore section, restricting the main feed to personal content and ads.

“That has upset a lot of news publishers because it could reduce views of their content drastically,” says Cohn. “But given what’s going on, I think it’s worth a try. Putting news content in the main feed isn’t working out.”

Why not just devise algorithms that can identify fake news and isolate it from the sites?

First, it’s difficult. Alan Mutter, a former newspaper editor and cable TV executive, who serves as a continuing lecturer at Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism, notes that research is underway to create markers that can be employed to identify bogus news and overt propaganda, but algorithms are notoriously inept at detecting nuance, tone, point of view – let’s face it, even objective fact – in editorial content.

Amanda Hickman, also a lecturer at the J-School and the director of BuzzFeed’s Open Lab for Journalism, agrees algorithms are not enough. “This idea of a mythical algorithm that solves a given problem is only effective when no one has an incentive to game that algorithm. And as we’ve seen, there’s plenty of incentive to game any algorithm that pertains to news—and a lot of other things, for that matter.”

So, along with new algorithms, says Hickman, large staffs of competent human overseers are necessary to make any meaningful dent in the flow of fake news. No algorithm has an indefinite shelf life. Sooner or later—probably sooner—someone will find a way around it. For the foreseeable future, then, slow and fuzzy analogue human brains, and a lot of them, will be necessary to separate fact from fiction on the internet.

But Mutter says social media will likely be damned no matter how it addresses fake news. Facebook had a bevy of human editors a year or so ago, he observes, then the company fired them all after conservatives complained that the content was skewing against their values.

“If they actually assert editing and veto power in an aggressive way, all hell will break loose,” Mutter says. “Also, just consider the amount of content accessible through these sites. More than 300 hours of new video are uploaded to YouTube alone every minute. The only way to establish any meaningful control would be if somehow someone created universal standards. Like if Nixon gets seven minutes then Kennedy gets seven minutes, or you can’t use the seven words that George Carlin talked about. We have to remember that these are companies that are giving people what they want, what they demand, if not what they need. Pillorying them is like blaming Gutenberg for the ‘Dewey Beats Truman’ headlines.”

Breaches of the First Amendment are another obvious concern, but the Fourth Amendment—which guards citizens from unreasonable searches and seizures—might also come into play. The Fourth Amendment often has been used as a broad shield to protect the privacy of common citizens; and in the opinion of many, an individual’s data might also be protected by such constitutional safeguards.

“Things will get dicey as social media gets together with government to find a solution to fake news,” says Ed Timke, a lecturer in Media Studies at Cal. “We sign up with these platforms for free, but it’s only ‘free’ in the sense that we don’t pay money. We give up data. And as these platforms collaborate more and more with government, we might find their ‘solution’ severely compromises our data and our privacy. That’s not a solution citizens will want.”

Ultimately, though, the onus may fall mostly on the consumer. Like fast food, these internet services have proven irresistible. And just as too many burgers and fries can devastate human health, they may be undermining the vigor of the body politic.

“I’ve been phobic about these things for a long time, and now I find it hard to resist wagging my finger and saying ‘I told you so,’” says Paul Duguid, an adjunct professor at Berkeley’s School of Information. “It’s reaching the point that we now say, ‘Oh, we have Facebook, we don’t need newspapers anymore. We have Google Books, so we don’t need libraries. We have Quantified Self, we don’t need doctors. The rise of the internet and digital technology has correspondingly led to intense anti-institutionalism. There is now this recurring naiveté, this belief that information can stand on its own, as if we’re all capable of interpreting everything we receive, that we don’t need to authenticate it. And if you attempt to defend these institutions, people drum up thousands of examples of corruption and errors. But that doesn’t mean we don’t need our institutions. It just means we need to build better ones.”