Picture this: It’s past 2 a.m. on October 1, and Berkeley is finally asleep. The night owls have started to nod off at their desks, and the early risers won’t be up for a few more hours. At first glance, not a creature seems to be stirring—not even a Kiwibot.

But look again. A light has just switched on in the homes of two Berkeley News team members (Fiat Lux!). Still in their pajamas, they pull their computers into their laps and wait for the news, first in Swedish and then in English: Has Berkeley won a Nobel Prize?

If the winner is Berkeley, a precisely planned chain of events is set into motion—beginning with an elaborate and exhaustive network of wake up calls.

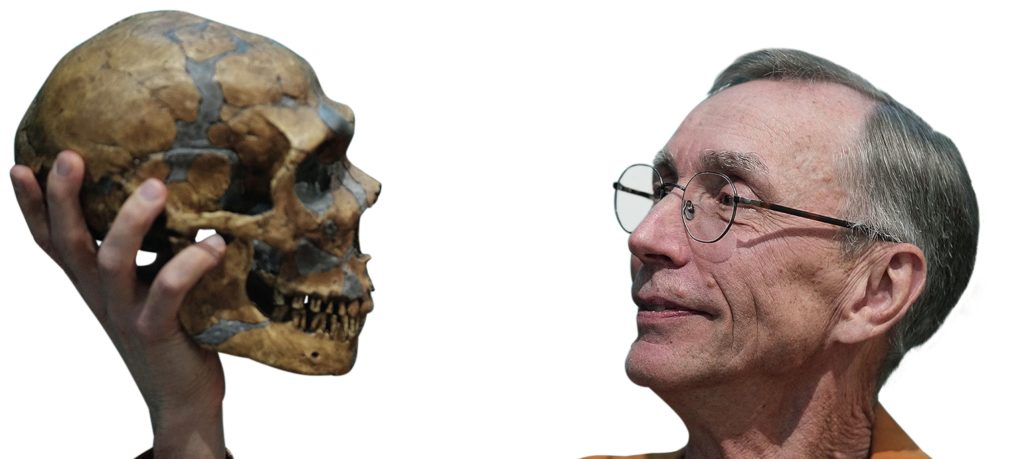

This week, as most of the country digs out dusty skeletons or secretly gorges on pre-sale Halloween candy, a few UC Berkeley hopefuls are preparing for the celebration of a lifetime—one that’s, frankly, pretty unlikely to happen. Of course, with an impressive 23 Nobel Prizes over the years (not to mention a few major players this round—did someone say Doudna?), Cal’s faculty have reason to be optimistic…ish.

[In fact, just as I was putting the finishing touches on this story, news broke that Dr. James Allison, former director of Berkeley’s Cancer Research Laboratory, had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his groundbreaking research in cancer immunotherapy.*]

Odds aside, on the day of the announcement, the Berkeley News teams have to be prepared for a win. And on the home front—as I learned last week from Gretchen Kell, Roxanne Makasdjian, and Bob Sanders of parent organization, the UC Berkeley Office of Communications & Public Affairs—what happens this week, in the dark recesses of early morning, has become something of media lore. It goes like this.

On four separate days—for the announcements in medicine or physiology, physics, chemistry, and economics—two Berkeley News members will set their alarms for the ungodly hour of 2:30 a.m. (that’s 11:30 a.m. Stockholm time). Not bothering to get out of bed, they fire up their laptops and watch the live stream online.

“It’s a little suspenseful the way they do it,” says Gretchen Kell, director of special projects and outreach for Berkeley News. There’s a door, she explains, which will sometimes remain closed minutes past the scheduled start time. Then suddenly, for no obvious reason, a hush will settle over the room. Nobel committee members file in, and the announcement is made, first in Swedish, while the Berkeley News members listen intently to catch mention of UC Berkeley.

With the phone tree in progress and the Berkeley News office lines due to start ringing any minute, it’s time for phase two.

“If it’s not Berkeley you can go back to sleep,” says Bob Sanders, manager of science communications for Berkeley News, who has been on the team for many iterations of the announcement process and remembers getting up to listen to AP on the radio.

If, on the other hand, the winner is Berkeley, a precisely planned chain of events is set into motion—beginning with an elaborate and exhaustive network of wake up calls.

One by one the lights around the Bay Area turn on: First, Sanders makes his preliminary call to the awardee (if it’s a science winner, that is—for economics, someone else makes the call). Some people are easier than others, he explains, but for the most part it takes him some work to coax out a reaction.

“They’re kind of speechless,” says Sanders. “Most people think it’s a hoax.”

Meanwhile, Kell starts calling Berkeley News staffers, and a video crew, media relations representative, and photographer are sent to the winner’s house. By 3 a.m. social media posts are going up, and by 4 a.m. the UC Office of the President has received the news. By 5 a.m. relevant press conference crews, the chancellor, and other top administrators are awake and mobilizing. Soon the deans and chairs of the department will be notified as well.

At this point, with the phone tree in progress and the Berkeley News office lines due to start ringing any minute, it’s time for phase two.

“You jump in the shower and drive to work,” says Sanders.

“I’m impressed that you shower,” Kell adds, laughing.

“No one really knows what’s in the minds of the Academy. But we have to take a guess. The last thing we want is for a winner to be announced and we aren’t

prepared.”

While Kell and Sanders head to work (showered or otherwise), Berkeley News director of broadcast communications Roxanne Makasdjian is “a nervous wreck.” Worried about missing her alarm and already anticipating what technical glitches the day may bring, Makasdjian has barely slept. She’s anxious for news, and as soon as the call comes in, she and her videographer are on their way to the awardee’s house. There, in addition to trying to get her own footage, part of her job is helping the winners “withstand the onslaught.”

As early as 3 a.m., the local media are at the house shining lights and knocking on the door. Sometimes they even manage to track down a home number and start calling. So it’s no surprise that, compared with outside media crews, Sanders and Makasdjian are friendly territory. “It’s not all about making sure UC Berkeley gets the glory,” Sanders says. “[The winners] know we’re there to help, and they appreciate it.”

Inside the house, the vibe is less showers of champagne and more congratulatory phone calls. (Though there has been known to be some jumping on the bed.) “Low-key giddiness,” is how Makasdjian describes it. “Like they’re containing the urge to jump up and down.”

Once the initial hullabaloo has died down, the winners are typically eager to get out of the house and back to campus. The first stop is often at their lab or home department where things can get emotional and, Sanders says, “you get a good sense of the weight of the moment.”

The thing is, Nobel-ity or not, Berkeley academics are committed first and foremost to their work. And Kell, for her part, has a special appreciation for the not-so-rare faculty members who insist on teaching class the morning of the announcement. For a Cal undergraduate, she explains, “It’s the greatest thing to be a student of a winner and to get to participate.”

What hasn’t changed over the years is the Berkeley-ness of the whole operation. Unlike the Academy Awards, Kell describes a “real homey feel.”

No matter the outcome, this week marks the annual culmination of months of predictions and preparations. Ideally, by now, the press releases will be written, the preliminary shots taken, the press conferences organized, the meeting rooms booked. The News team has already touched base with potential winners to shoot some preemptive video footage and schedule tentative interviews—just in case. Which, says Sanders, the Nobel hopefuls aren’t always too happy about. They tend to be a bit on the shy side. And more importantly, they don’t want to jinx it.

I wondered—how does Berkeley News come up with their list of frontrunners in the first place? With no official roster of nominees, making predictions seems like a murky business. And in the past it probably was, but now, says Sanders, “We listen for the scuttlebutt. There’s like a cottage industry of predictions.”

Still, Kell adds, when it comes to who actually wins, your guess is as good as anyone’s.

“No one really knows what’s in the minds of the Academy. But we have to take a guess. The last thing we want is for a winner to be announced and we aren’t prepared.” Which, much to their chagrin, has been known to happen.

Back in 2000, the then-media relations director, Marie Felde, was heading to Egypt for vacation just before the award week. Not expecting any Nobels that year, she said jokingly that, in the case of a surprise win, Kell was in charge.

“And wouldn’t you know, someone won,” says Kell, throwing up her arms. It was economist Daniel McFadden who, like the News team, “just couldn’t believe he’d won.” They did manage to pull off a proper celebration, but it was a hustle.

“I’m ambivalent—intellectually I want it to happen and I know I’ll be thrilled,” Makasdjian admits. “But I’m a nervous wreck, hoping for relief.”

Since then predictions have become more accurate. “We’re not surprised much anymore. That was pre-Internet,” says Sanders. But with the arrival of the Internet, it’s also harder to get attention for your work—and readiness correlates directly with media publicity. “You don’t have to be ready,” Sanders adds laughing. “But if you’re not, you lose an opportunity to show off.”

What hasn’t changed over the years is the Berkeley-ness of the whole operation. Unlike the Academy Awards, Kell describes a “real homey feel.” Rather than pesky media outsiders, she and her team feel like they’re part of the celebration. For Sanders, making the early-morning phone call to the newly crowned Nobelist can be intimidating, but he’s often known and interviewed these people for years. “I’m most nervous about getting the science right,” he says, in true science writer form.

Of course, good feelings aside, there’s an enormous amount of work, and the inevitable mistakes, that go into this celebration, which Kell calls a “day-long performance.”

“It’s an exhausting day for me,” says Makasdjian, slumping at the mere thought. “From 2:45 a.m. to 6 or 7 p.m. without stop.”

Which begs the question, does the News team even want Berkeley to win or are they secretly hoping for the day off?

“I’m ambivalent—intellectually I want it to happen and I know I’ll be thrilled,” Makasdjian admits. “But I’m a nervous wreck, hoping for relief.”

“It’s the middle of the night and you’re sitting in the dark watching the press conference, hoping it’s Berkeley,” says Kell, sounding tired but determinedly cheerful. There’s something special, she says, about being awake and one of the first to know. “And on the other hand…it’s a big day.”

Finally, I ask what seems to me the obvious follow-up—Do they place bets within the News team? Just how much money is riding on these predictions? To my amusement, they responded with an immediate and almost affronted no.

“Why don’t we?” Makasdjian wonders aloud, before answering her own question. “I guess we have a reverence for it.”

Current forecasts? Kell hazards a guess that Jennifer Doudna will win at some point. But she doesn’t want jinx it by guessing.

Besides, she says, “The mystery—that’s part of the fun.”

*As for Dr. Allison, Berkeley News says that “because he’s no longer at Berkeley, we can’t claim the prize as ours.” Nevertheless, they’ve put out a press release in which Allison, who conducted his award-winning research here, claims Berkeley as his: “I don’t know if I could have accomplished this work anywhere else than Berkeley.”