Janet Daijogo ’59, C.Mult. ’60 still remembers the thunderous pounding of military police at the door of her childhood home. The Japanese had just bombed Pearl Harbor, and the United States panicked, unjustly criminalizing Japanese American families. “I remember just grabbing onto my mother, and then at some point the military police were going into the bedroom, my parents’ bedroom, and they were going through their drawers,”1 Daijogo recalls of the traumatic search of her family’s home. At only five years old, Daijogo could not fully comprehend the events taking place, but she says, “I remember thinking that there was something terribly wrong; and also there was a helplessness because nobody could protect me from this experience and from what was going to happen.”2

"Mainly I remember a lot of the loss, like they couldn’t take my brother’s and sister’s crib, of course, and for some reason that stands out in my mind."

While the United States government had been imposing discriminatory laws and policies on Asian people for years, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the racism and unjust treatment of Asian Americans skyrocketed. The US government feared that Japanese Americans might act as espionage agents and reacted by imposing new policies that limited their freedom, such as creating twelve restricted zones on the West Coast that would enforce curfews.3 Then, on March 31, 1942, Japanese Americans living on the West Coast were required to report to control stations to register the names of all family members and forcibly relocated to internment camps.4 They were given less than two weeks’ notice—and in some cases just four days—to settle their affairs and gather belongings. Daijogo remembers her parents being allowed only two suitcases each, which needed to include kitchen items like forks and plates. When she recalls packing before internment, she says, “Mainly I remember a lot of the loss, like they couldn’t take my brother’s and sister’s crib, of course, and for some reason that stands out in my mind. I can see the crib sitting there and thinking, ‘We can’t take that.’”5

The first camp they went to was Tanforan, a racetrack in San Bruno, California. Daijogo and her family were assigned to live in the barracks, but she remembers that some families were sent to live in the horse stalls. She remembers the barracks having wooden floors with cracks between the slats wide enough that she was able to see the dirt of the earth beneath the floor. The fences that surrounded the camp became a big source of fear for Daijogo and she remembers trying to stay far away from them. The fences represented more than the fact that they were in imprisoned, Daijogo says, “I remember being very afraid. Those fences—you could see out of the fences—and what I saw, what was outside of the fences, was the rest of life, the people out there.”6

When her family was finally freed from internment, Daijogo was entering third grade. Upon release from detention, her parents emphasized the importance of moving forward with education instead of looking back. While Daijogo describes her father as a somewhat quiet man, she remembers that he was not shy about sharing his pride in her achievements at school. “I remember when I was in high school I became the president of my student body, and my dad bought me a gift…He was just so proud of you if it had to do with your schooling; that was very important to him.”7 Her mother and father had both attended Cal, and Daijogo knew she would follow their legacy. She says that being educated was ingrained in her from a young age. “I remember I came home one day as a senior in high school, and I said, ‘Mom, do you know that lots of my classmates are not going on to college? Is that legal?’ Because I actually thought it was like a mandate: you finished high school, you chose a college, and then you went to college.”8 Her mother attended UC Berkeley during a time when attending a university as a woman, let alone an Asian American woman, was not common, and felt incredibly proud to have attended Cal. Daijogo followed suit, studying child development.

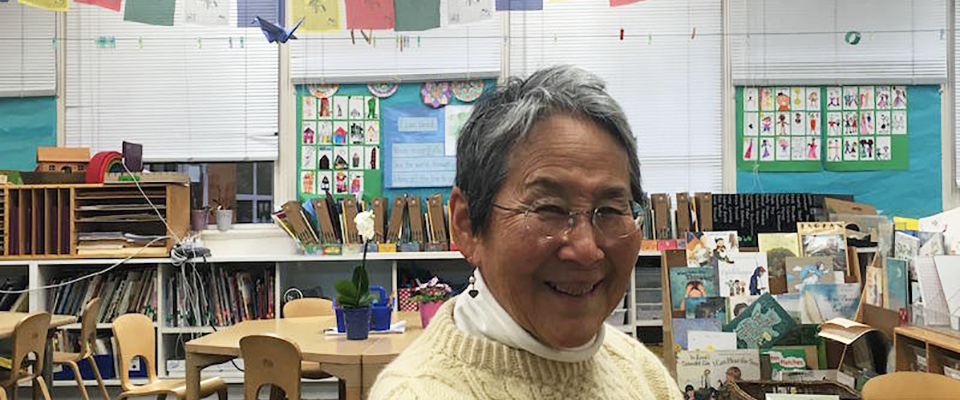

Daijogo had always pictured herself teaching older children, and describes becoming a kindergarten teacher for children who had experienced trauma in the beginning of her career as “one of those serendipitous opportunities.”9 As someone who had experienced significant trauma through internment during the formative years of her childhood, Daijogo felt she could relate to the experiences her students had endured. Because their anxiety and fear impacted their behavior, Daijogo knew she would have to teach them to handle their emotions in order to clearly express themselves—and that she would have to lead by example. That meant she would have to face her own fears that had developed from her time in internment. Daijogo mused, “Why do you think that child should believe you if you don’t believe it?” She says, “That was an essential question. It helped me solve a lot of issues that I thought about.”10 In order to find her voice and a way to center herself, she turned to Aikido, a martial art that focuses on achieving harmony to resolve conflict.11

"…the power is manifest[ed] as natural confidence instead of a need to dominate the other, or to dominate parts of yourself."

According to Daijogo, Aikido demanded that she express parts of herself that she hadn’t before.12 Daijogo learned about managing conflict, both internal and external, by centering herself. “All martial arts have the sense of a center of being…. It is a place that really has the capability, if you access it, of being the command center and the decision making center for your life…. So it’s a center, a place of stability and of ‘okayness,’ of feeling good, of relaxation and of power. But the power is manifest[ed] as natural confidence instead of a need to dominate the other, or to dominate parts of yourself.”13

After seeing the positive impact this inner work had in her own life, Daijogo knew she needed to teach her students how to apply the principles of energy and centering to help them express their emotions. According to Daijogo, the children she worked with, and most people for that matter, had no idea about their “center”. She started including lessons about energy in her curriculum as something children can hone in to to ground, or center, themselves.

Daijogo teaches her students to find their voices by recognizing the difference between the statements “I am centered now” and “I am not centered now.” She related classroom activities back to the students’ energy work to help ease anxiety. Daijogo is particularly sensitive to the anxieties her students face surrounding change. She remembers the anxiety she experienced after being forced out of her childhood home saying: “I think it’s mainly about losing the place you thought you were going to stay, your home, and you were going to somewhere but nobody knew where you were going.” This made her think carefully about helping students adjust to transitions in the classroom to work through the potential anxiety they might experience around change. She explains, “I’m very good at school with helping my kids make transitions…. I will go over something ad nauseam, I’m sure, for the children. ‘We are going to the gym right now, and the gym is a big place and we saw it.’”14

Although she no longer works exclusively with children who have experienced trauma, Daijogo has continued to see the impact of using Aikido principles in the classroom. Her students are able to self-correct, using simple reminders to tune into themselves and make “blends” during conflict. A “blend”, in Aikido, stems from the idea that conflict is two different energies coming together instead of clashing. Daijogo suggests to her students that they learn to make blends when conflicts arise, or to work with something instead of against it. She describes an instance in which a child was jealous that another child got a bead as a reward and started to cry. “I knew why she was crying, and I said, ‘You are feeling really bad because you didn’t get that bead…. What you’re feeling inside yourself is called jealousy. When you’re jealous, it’s upsetting, so you’re crying because you’re upset, because you’re wishing that she didn’t get it or that you got one, too.’ And I said, ‘Another thing that you can do is you could go and talk to her about it and ask her how did she manage to get that bead, and maybe she could give you some advice?’”15

The child then went and talked to the other student. Then, Daijogo said, “About two days later—when someone else got a bead—that same little girl went up and said, ‘Congratulations.’ So she had shifted something in herself, made a blend that worked for her and was able to do this socially smart thing.”16

Through implementing Aikido principles in her curriculum, Daijogo has made a difference in the lives of countless children. She has made meaning out of her own traumatic experience with internment as a child by finding her own voice and purpose in helping other children find their center. In 1990, her extraordinary work helping children foster self-esteem was recognized with the Milken Educators Award, which honors educators who inspire excellence in education.

Although she only spent a short amount of time with these children, Daijogo has made a difference in their lives forever. She compares teaching children to center themselves and create blends to planting a seed, “I’ve always said we plant the seeds…. I think the energy dissipates and maybe dissolves, and then it reforms into a seed…. If the seed is in the right circumstance, and it receives water and sun, it will blossom, and it will serve the world.”17

By Kiley Treacy

Resources: