For John Lam ’24 and Alishba Sardar ’23, UC Berkeley was the pinnacle of higher education. If they could gain admission to Cal, it would be a major accomplishment and just the beginning of what was sure to be a successful life and career. But the odds seemed against them. Lam was a system-impacted student and Sardar was a former foster youth. There wasn’t a clear-cut pathway at Cal for them.

Nontraditional students, or students from marginalized groups, often don’t have access to resources on campus that meet their needs. Most come to campus without the guidance to navigate through the complex matrix of the university system. Even basic needs are hard to get met, and students like Lam and Sardar have to seek out their own guidance to succeed in college.

They got in, and were awarded The Achievement Award Program (TAAP) scholarship, which funds two to four years of tuition for students coming from low-income and first-generation backgrounds, and provides support through their undergraduate scholastic careers.

“I think that, me being a TAAP Scholar, there has been a tremendous amount of support that I’ve gotten that is quite intangible,” Lam says.

Gaining admission to the number one public university was only the first step in succeeding at Cal. The next step was finding resources to succeed in the classroom.

“Housing support is one of the biggest issues that plague our population,” Lam says. He cites an article from Berkeleyside that points out that only 22% of undergraduates and 9% of graduate students are housed by the university. There are 45,000 Cal students, but only 9,875 beds. That leaves the private sector as the next best place to find housing, an option that is not always viable for students. For system-impacted students, the challenge of finding housing is compounded by biases against people who’ve been in the penal system. “A person who has a criminal background, for instance, or who has bad credit, who has no credit history at all, their opportunity, their chances of securing housing, are even much less than a person who is a student who has family support,” Lam points out.

Lam had to work two jobs on top of his course load to be able to pay rent.

Seeing this as a pressing issue facing students from marginalized backgrounds, Lam wanted to find ways to support these students. With his friends, fellow Cal students David Carranza ’23 and Jonathan Dena ’23, he co-founded Cre8Innovations, a nonprofit organization that takes a holistic approach to advocacy for students by considering their housing, future career prospects, and financial literacy.

As a former foster youth, Sardar had a similar goal to provide resources and support for former foster students. She noticed there was a lot of research done on foster youth, but none of the research included the real stories of the students themselves.

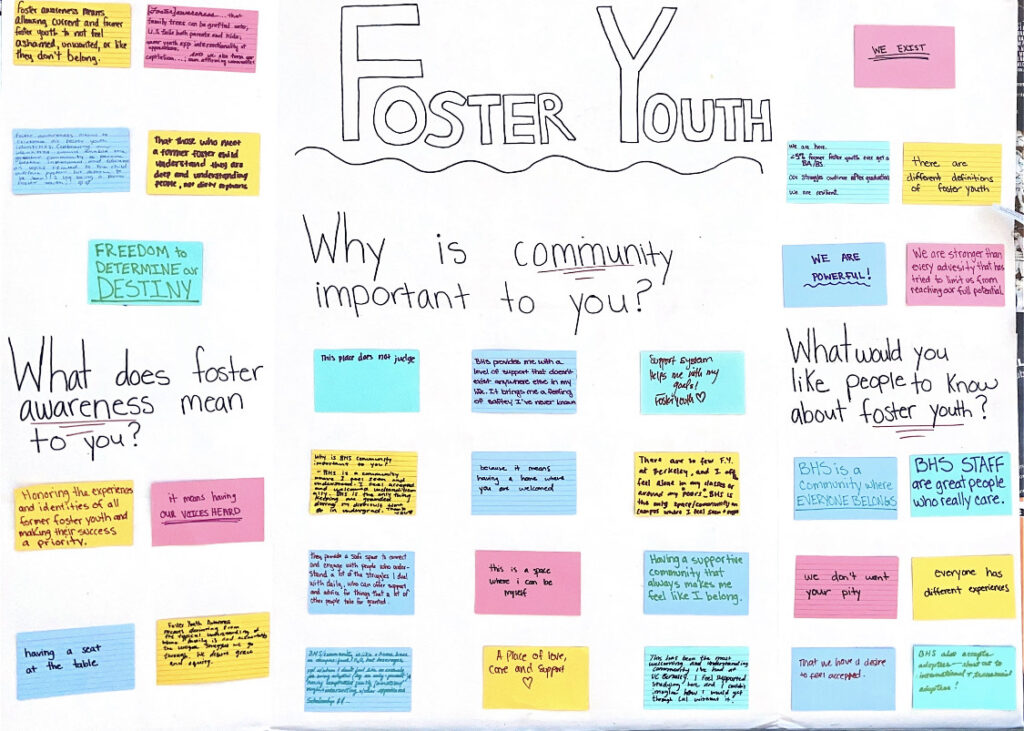

“I remember coming into Berkeley Hope Scholars and there were two other students in there,” she said about a peculiarity she noticed. She recalls their conversation: “Don’t you think it’s weird that there are so many other research teams, but we don’t have anything about foster youth, but yet… There’s so much research on us. Everyone’s talking about us and researching goes, but none of us are telling our own stories. And we’re like, ‘We should do something about it!’”

Berkeley Hope Scholars is a retention program that supports students who are former foster youth, probation youth, or youth orphaned before 18. Since she entered the program, Sardar has helped expand and improve the program through skills and tools she’s learned from being a TAAP Scholar. The program has widened its eligibility, ideas for workshops, and new projects and research for the program.

Sardar says that the existing research she saw about foster youth was sterile and impersonal. Her research looked at the experiences and the positive outcomes for former foster youth in the University of California system. She pinpointed that the more positive reinforcement foster youth had around them, the higher the chances they had of going to college. “I’ve had students say, ‘I would have dropped out if it wasn’t for this program.’” Sardar says that the impact of these programs is unrecognized.

Sardar admits that doing this work is hard and she’s faced some challenges. Sometimes getting campus administrators to answer emails is a job in itself. “If you’re not able to respond to my email or my professors’ emails, then what is the support available at those UCs?” she wonders. Searching for the root of the problem, Sardar looked at the support at each UC campus, and what students said about it, and compared the responses. She still hasn’t heard from some campuses. “At the same time, [I remind] myself that if I don’t do this, then my foster siblings who are going to come to college, they’re going to have to do it.”

“We want to leave behind a legacy, a platform, for other students who are from marginalized backgrounds—not only just transfer students, but students who are system impacted, former foster youths to come to campus to have that immediate support,” says Lam.

Alumni: Learn how you can support The Achievement Award Program.

Students: If you would like to apply for The Achievement Award Program, visit the Cal Alumni Association Application Portal. Open only to prospective first years and junior transfers.