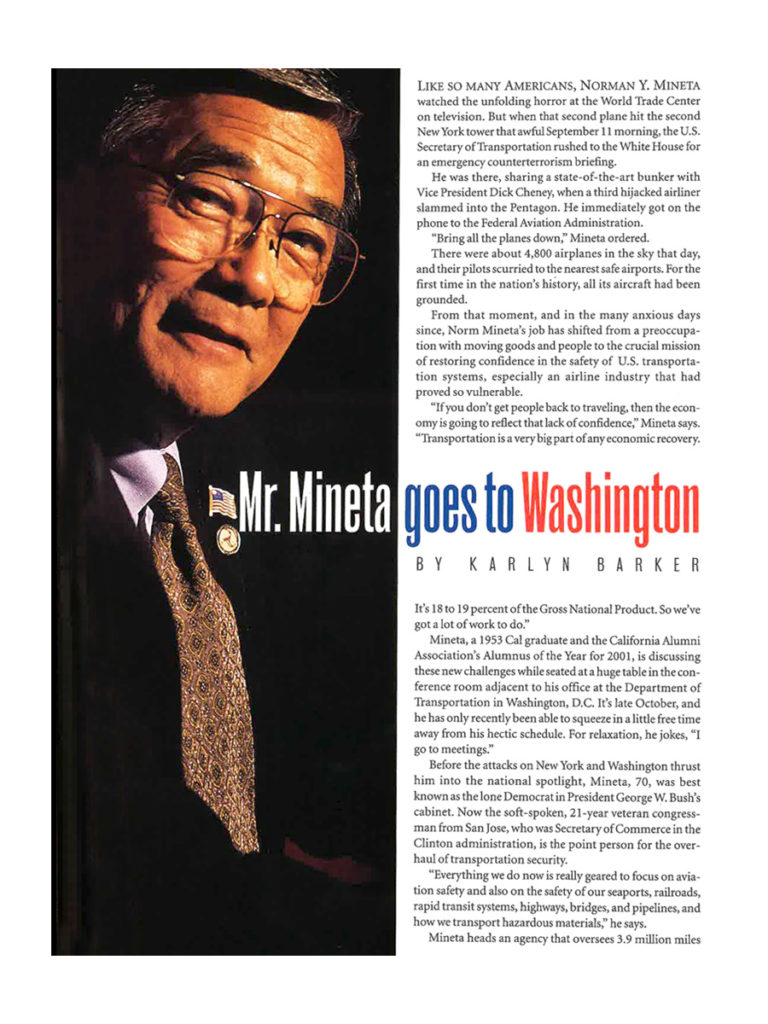

Like so many Americans, Norman Y. Mineta watched the unfolding horror of the World Trade Center on television. But when that second plane hit that second New York tower that awful September 11 morning, the U.S. Secretary of Transportation rushed to the White House for an emergency counterterrorism briefing.

He was there, sharing a state-of-the-art bunker with Vice President Dick Cheney, when a third hijacked airliner slammed into the Pentagon. He immediately got on the phone to the Federal Aviation Administration.

“Bring all the planes down,” Mineta ordered.

There were about 4,800 airplanes in the sky that day, and their pilots scurried to the nearest safe airports. For the first time in the nation’s history, all its aircraft had been grounded. From that moment, and in the many anxious days since, Norm Mineta’s job has shifted from a preoccupation with moving goods and people to the crucial mission of restoring confidence in the safety of U.S. transportation systems, especially an airline industry that had proved so vulnerable.

“If you don’t get people back to traveling, then the economy is going to reflect that lack of confidence. Transportation is a very big part of any economic recovery. It’s 18 to 19 percent of the Gross National Product. So we’ve got a lot of work to do.”

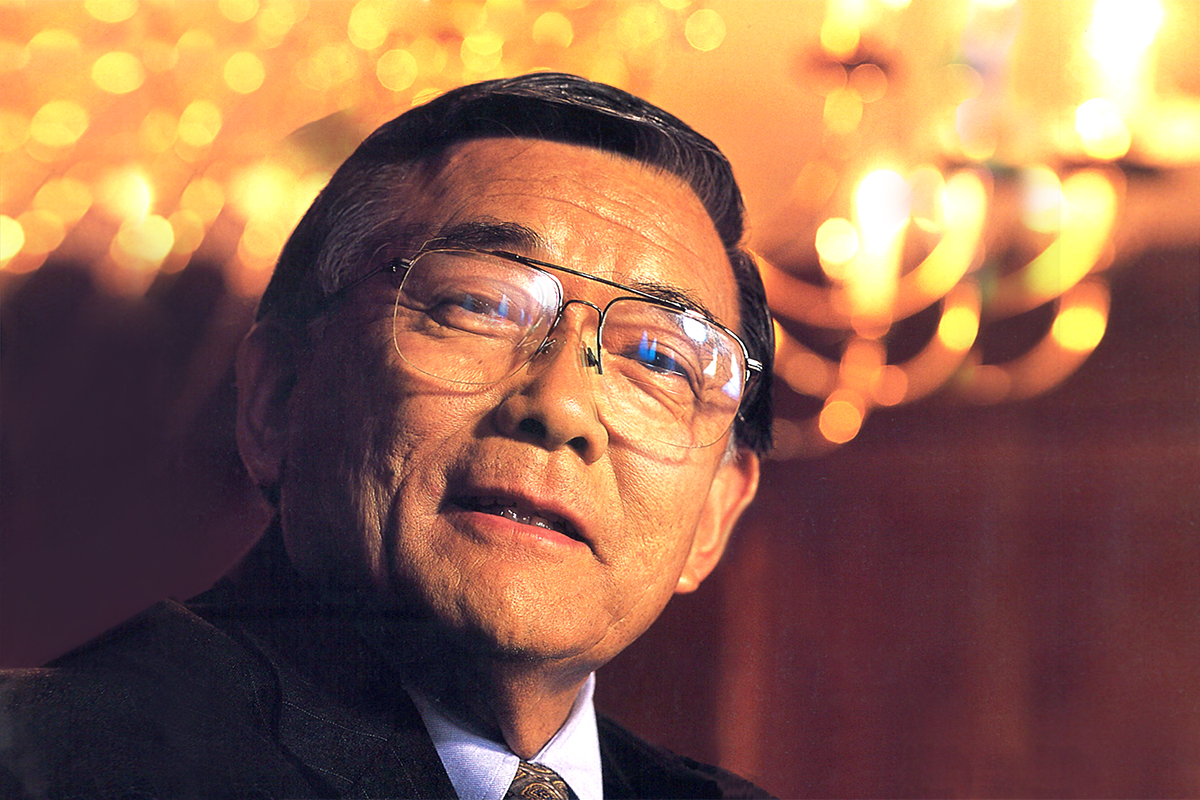

Norman Mineta ’53

on post 9/11 ecomonic recovery

Mineta, a 1953 graduate and the Cal Alumni Association’s Alumnus of the Year for 2001, is discussing these new challenges while seated at a huge table in the conference room adjacent to his office at the Department of Transportation in Washington, D.C. It’s late October, and he has only recently been able to squeeze in a little free time away from his hectic schedule. For relaxation, he jokes “I go to meetings.”

Before the attacks on New York and Washington thrust him into the national spotlight, Mineta, 70, was best known as the lone Democrat in President George W. Bush’s cabinet. Now, the soft-spoken, 21-year veteran congressman from San Jose, who was Secretary of Commerce in the Clinton administration, is the point person for the overhaul of transportation security.

“Everything we do now is really geared to focus on aviation safety and also on the safety of our seaports, railroads, rapid transit systems, highways, bridges, and pipelines, and how we transport hazardous materials,” he says.

Mineta heads an agency that oversees 3.9 million miles of public roads, 2 million miles of oil and natural gas pipelines, 120,000 miles of major railroads, and more than 5,000 public-use airports. Its transportation networks also include 500 urban public transit systems, 25,000 miles of commercially navigable waterways, and more than 300 ports.

Prior to the attack, the department had roughly 100,000 employees and a $58.7 million budget-numbers that will likely go up in this new security-conscious environment.

Take, for example, the country’s sky marshalls. Mindful of the eerie coincidence, Mineta notes that the federal air-marshal program was announced by President Nixon on September 11, 1970, following the hijacking of a commercial airliner. At its height, the program deployed nearly 2,000 armed guards. “But as we got away from the incident that prompted the sky marshals,” Mineta says, the specially trained security force was allowed to dwindle. “On September 11, 2001, we were down to 32 sky marshals.” To protect all the flights in the country, Mineta says, “It’s going to require an army of federal marshals.”

Despite, or maybe because of, the serious matter he must deal with these days, Mineta seems to relish talking about his days at Cal. “I loved Berkeley,” he said, grinning widely. He arrived on campus as a freshman in September 1949, intent on becoming an aeronautical engineer. Since there was no such major at the University back then, he started off pursuing a degree in mechanical engineering. He was doing just fine, he says, “until I took calculus.”

Even with a tutor, the subject derailed his career plans. “I decided that, for the safety of the country and my own future, I had better find something else to do,” jokes Mineta. He switched to business administration.

Cal’s enrollment then was about 21,000 students, only a small number of whom were Asian American. But the campus had plenty of World War II veterans, the last of a large group that got an education under the G.I. bill. “These folks were no-nonsense. They were just there to study and get through school,” Mineta says. “They were a great bunch to be with, but there wasn’t much socializing. The veterans there were all hustling, and that spirit got into the rest of us.”

Mineta lived in a boarding house his first year, then moved to Bowles Hall. To get to know more students his age, he became involved in class activities. Having been student body president at San Jose High School, it seemed a natural step to serve on the freshman, sophomore, junior and senior class councils as he moved through Berkeley.

One of Mineta’s fondest Cal memories is the night the new chancellor, Clark Kerr, came to dinner at Bowles Hall. “I believe it was his first public appearance as chancellor,” Mineta says, smiling at the memory. “On Wednesday nights we all had to wear a coat and tie to dinner. I had the opportunity to be at his table, so I just thought the evening was terrific.”

Mineta concedes that he was probably a bit straight-laced as a student, even by the conservative standards of the 1950s. It rankled him, for instance, when he saw someone drinking beer in the men’s rooting section. He cared passionately for football: “I really loved Berkeley, and in those days we had great football teams,” he enthuses. “We went to the Rose Bowl. So, you know, life was good.”

After graduating in 1953, Mineta joined the army and served as an intelligence officer in Japan and Korea. When he got out of the service in 1956, he worked at his father’s insurance agency before entering politics in San Jose.

Mineta, whose family was among the 120,000 Japanese Americans forced into internment camps during World War II, broke barriers for Asain Americans in government service. He was elected to San Jose’s City Council in 1967, then served as its mayor from 1971 to 1974- the first Asian-American mayor of a major U.S. city. On September 4 of this year, San Jose officials voted to rename the San Jose International Airport after their popular native son.

From 1975 until 1995, Mineta served in the U.S. House of Representatives, where his legislature and policy agenda ranged from economic development, science, and technology to the environment and civil rights. He was a key member of the House Public Works and Transportation Committee and served as that panel’s chairman between 1992 and 1994. He also co-founded the Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus and served as its first chairman.

In Congress, Mineta championed increases in support for transportation infrastructure and helped author the landmark Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991, which shifted highway and mass-transit planning to state and local governments.

After leaving the House, he chaired the National Civil Aviation Review Commission, which studied the ways to reduce air-traffic congestion and aviation accidents, and was a vice president at Lockheed Martin Corporation. Then President Clinton named him Secretary of Commerce, making him the first Asian Pacific American to serve in a Presidential cabinet.

On December 29, 2000, Vice President-elect Cheney called to see if his old friend from the House would be interested in joining the Bush administration. Mineta spent the New Year’s holiday weekend calling scores of Democrats, including Clinton and Al Gore, to see what they thought of the idea. He also consulted former Secretary of Defense William S. Cohen, the lone Republican in Clinton’s cabinet.

“I didn’t want to be diminished as a Democrat, and I didn’t want to be considered a turncoat,” Mineta explains. Confident that he was up to the job, and convinced he could be “part of the healing process” after the divisive election, he flew to Austin, Texas on January 2, where he met Bush for the first time.

“I was offered the job about an hour and a half into the interview,” Mineta says. “Bush never outlined what he wanted to see in the transportation department. I think he was trying to assemble people in the cabinet who were strong individuals.”

By late October, Mineta’s workload at the agency had eased a bit, and he was no longer putting in nearly 20-hour days that were typical immediately after the attacks. He spent so much time then at the office, where the air conditioning is very drying, that he was briefly hospitalized with a bad nosebleed. “Everything checked out. I feel fine,” Mineta says. He comes to work sporting his department’s pin and a U.S. flag on his lapel. And he still wears his Berkeley ring.

He and his wife, Deni, live on the Rhode River near Annapolis, Maryland, and relax by taking their power boat out on the Chesapeake Bar (his wife loves to fish). They also try to see the Washington Redskins when they play at home.

Given the current situation, Mineta’s experience in the internment camps put him in a unique position to counsel against any backlash against Muslim Americans. He was 10 years old when authorities sent his family to the Santa Anita racetrack in Southern California. He remembers how they confiscated his baseball bat. The Minetas ended up in Heart Mountain, Wyoming, near Cody.

“All 120,000 of us were put in camps behind barbed wire, with guard towers every 300 yards, and searchlights and machine guns. They told us we were in the camps for our own protection. But we said, ‘If we’re in here for our own protection, why are those machine guns pointed at us?’”

Norman Mineta ’53

on his internment camp experIEnce

Mineta’s father got a job in 1943 teaching Japanese to U.S. Army personnel at the University of Chicago. The family was eventually allowed to join him in Evanston, Illinois, where Mineta was a Boy Scout and ushered at Northwestern University football games. The coach there, he proudly points out, was Lynn “Pappy” Waldorf, head coach at Cal by the time Mineta got there.

The family moved back to San Jose after V.J. Day. “From my perspective,” he says, “what happened to us in 1941 was because people could not make the distinction between the Japanese who were flying the airplanes that bombed Pearl Harbor and those Japanese Americans living in California, Oregon, and Washington.”

President Bush, Mineta says, has gone out of his way to prevent similar discrimination against Muslim Americans and others who might now be viewed with suspicion. He cites Bush’s visit to an Islamic center in Washington the weeks after September 11 and the President’s decision to invite Sikh leaders to the White House soon after a South Asian Sikh was killed in Arizona.

Even with all the security measures at U.S. airports now, including increased screening and the computer-assisted personal profile system, none of it has to do with racial characteristics, Mineta says. “It’s about: Did you pay cash for your ticket or use a credit card? Is it a one-way ticket or roundtrip? It’s not about racial profiling.”

In Congress, Mineta was the driving force behind passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which officially offered apologies for the injustices suffered by Japanese Americans during World War II and authorized payment of $20,000 to each person who was interned. “If President Roosevelt had done and said the same things as President Bush has done and said,” Mineta says, “I wonder if we would have been put in those camps.”

Norm Mineta received his own compensation of sorts for the baseball gear he lost so many years ago. After he left Congress, he was given the gift of a very special and valuable bat. It’s signed by Hank Aaron and his “Home Run King” counterpart in Japan, Sadaharu Oh, and is proudly displayed in Mineta’s Washington office.

Karlyn Barker ’68, editor of The Daily Californian as an undergraduate, was a reporter and editor at The Washington Post for nearly three decades.