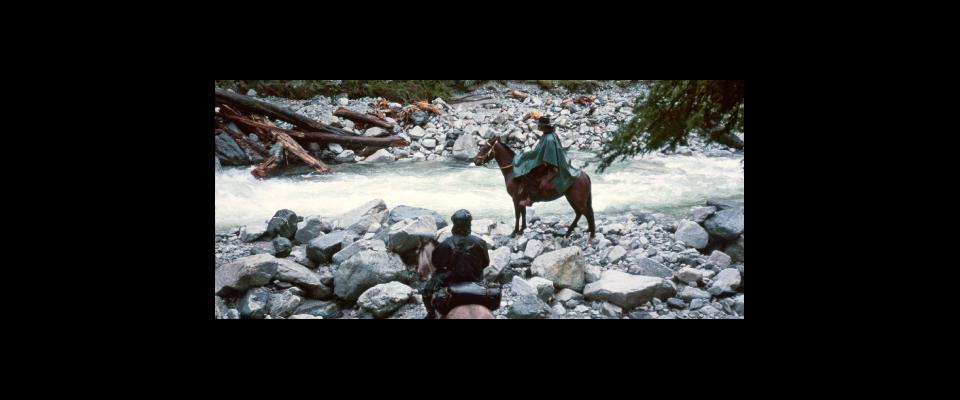

On horseback in Southern Chile.

The Yosemite of Chile is located in Northern Patagonia about 60 kilometers, as the condor flies, east of the city of Puerto Montt. Its true name is El Valle de Cochamó—and that is where we were headed, four of us on horseback, riding slump-shouldered in the pouring rain.

The horse I rode was called Miti Miti, for mitad mitad, or half-and-half. Fabián, who owned the horses, explained that when they were gelding Miti, one of the animal’s testicles retracted in terror and they were only able to complete half the job.

Fabián was our huaso, as the Chilean cowboys are called, and he dressed the part, in a wide-brimmed hat, heavy woolen poncho, and hairy goatskin chaps. One leg was black, the other white. In street clothes he was unprepossessing but the savage-looking costume transformed him into something half-mythic, half-animal. He looked like a satyr, or the great god Pan.

The rest of us—Jim, Pedro, and I—looked alien by comparison in our multiple layers of brightly colored synthetics. Not enough layers, in my case. Shortly into the journey, the cold and damp began traveling up my fingers. My elbows started to ache and I shivered in the saddle. “Tienes frio?” the huaso asked, as I leaned down to warm my hands on Miti’s lathered flanks. Fabián’s expression was quizzical, as if being cold were a novel condition in these parts.

“Frio y mojado,” I answered. Cold and wet. “The rain never stops.”

Pedro sidled up, water streaming down his face and dripping off his beard. Originally we had planned to do the trek on foot, and Pedro was our guide. The horses and huaso were an afterthought, inspired by the specter of flooded trails and mud up to our teeth. “That’s how it is in the South,” Pedro said.

The South. El Sur. Most countries are on more or less equal terms with all the points of the compass, but Chile is disproportionately north–south, a longitudinal splinter of geography wedged between the Pacific Ocean and the spine of the Andes.

We were moving east, and if we kept at it, would soon be in Argentina. The transnational route over the Paso El León was pioneered by Jesuit missionaries and later used for cattle. Among those who reportedly drove their herds over the pass to the slaughterhouse in Cochamó were Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. The American outlaws ranched across the border for a few years until Pinkerton agents closed in on them and they were forced to run.

“My country’s Wild West” is what the great Chilean poet Pablo Neruda called El Sur. Born in Temuco in 1904, Neruda (whose real name was Neftali Ricardo Reyes Basoalto) was a son of the South, and his memoirs are heartily recommended to anyone traveling to the region. If nothing else, he will prepare you for the weather.

“I’ll start out by saying this about the days and years of my childhood,” Neruda begins his story: “the rain was the one unforgettable presence for me then.… Sometimes it rained for a whole month, for a whole year. Threads of rain fell, like long needles of glass snapping off on the roofs or coming up against the windows in transparent waves, and each house was a ship struggling to make port in the ocean of winter.”

It was like that in the village of Cochamó, where everyone wore rubber boots and nobody smiled. We had holed up there for a couple nights, in Pedro’s creaky ark of a cabin, waiting for a local bus to deliver Jim’s backpack, lost on the connecting flight from Santiago. To kill time, I wandered around town snapping photos in the rain. From postcards, I knew that on clear days the church steeple was framed by the deep blue of the estuary and the looming white cone of Volcán Yate beyond. Today there was no volcano, no horizon line—just sea and sky bleeding together in a wash of watercolor gray. After a few exposures, I switched to black and white.

In the afternoon, Jim and I walked to the river mouth to fish, but the wind came in gusts down the fjordlike estero and played havoc with our lines. Flies aimed with precision at 12 o’clock most often landed in a heap somewhere around 8:30 or 9.

“A fine and pleasant misery,” Jim said cheerily when we finally quit and headed back into town.

“A fine and pleasant misery,” I echoed, less so.

That line, the title of a favorite story by outdoor humorist Patrick McManus, has been invoked by Jim and me—buddies since high school—countless times on our adventures. Like the time in college when we flipped my dad’s canoe and got pinned up against a rock (the canoe was crushed like a can and Jim busted his nose as he went under the gunwale). Or the time, many years later, when we broke down in the middle of the Sahara and spent an uneasy night in the dunes, wondering what would come next (one of our Mauritanian companions, thanks be to Allah, was a wizard mechanic and got us running again in the morning). Or the many, many times we got lost backpacking or skiing or climbing, yet always managed to get found again after much backtracking and bushwhacking, all the while remarking what a fine and pleasant misery we were having.

This trip was different. For one thing, an editor back home was expecting a story from me, complete with crisp slides of breathtaking scenery (The Yosemite of Chile!). For another, my wife and I were expecting our first baby, and the days of jetting off to far-flung locales with vague intentions of writing about it afterward were beginning to look like another lost artifact of youth. As much as I looked forward to fatherhood, I also sensed that a door was closing behind me. And that realization, even more than the gloomy weather, colored my mood.

Trudging back through town, Jim and I stopped off at a little general store (El Supermercadito) to procure samples of the local produce—a bottle of wine and a hunk of smoked Atlantic salmon grown right there in the Pacific. Outside the store a hand-lettered sign read “Señor Turista: Enjoy the natural wonders of Cochamó.” But that night, I, Sr. Turista, could only grump in my journal: “Volcanoes outside our window but we can’t see them. Trout in the river but we can’t catch them. Rocks in the valley but we can’t climb—too wet!”

As we saddled up the next morning, I still hoped we’d get to ride as far as the Paso El León, but that plan too hinged on the rain. Days earlier a huaso had drowned when he and his horse were swept away in a river crossing. The news was on the front page of El Llanquihue, the Puerto Montt newspaper. An accompanying photo showed someone holding the drowned man’s hat—the only vestige found of him.

When we arrived at Rio Piedras, the water ran fast and high, but not very wide. It hardly looked life-threatening. Fabián crossed first, to test it, then returned to make sure we could safely follow. Pedro and I crossed without incident, but Jim was midstream when his horse began to falter, the mare’s eyes flaring in alarm as her rump swung in the current and started to sink. With a furious yawp, Fabián spurred his horse and went crashing into the river just downstream, blocking their slide. In a flash, he seized the reins and, as if by sheer force of will, managed to get both animals safely up the far bank. Jim hardly had time to panic. Still, it had been dodgy enough that further river crossings—and border crossings—were ruled out.

We continued on, the trail narrowing as we climbed into virgin rainforest. Very little light made it through the canopy, and it took time for our eyes to adjust to the profusion of life all around. Some of it was familiar: the Spanish moss bearding the branches, the fungi erupting out of the duff. More of it seemed sumptuously exotic—thick vines dangling from the canopy, bromeliads bursting from the crotches of trees, fuchsias and bellflowers ornamenting the undergrowth.

When people compare Cochamó to Yosemite, the comparison often extends to the surrounding old-growth forests, and certainly one can find analogues. The massive and endangered alerce trees, for example, could be considered Chile’s answer to Yosemite’s giant sequoias. The contrasts, however, seem greater still. The Valdivian forest—dominated by broadleaf, as opposed to coniferous, evergreens—is roughly as far south of the equator as Redwood National Park is north; yet, despite the latitude and the air temperature, it feels almost tropical in character. Ecologists call it temperate rainforest, but I prefer Neruda’s descriptor. He called it selva fria—cold jungle—and rhapsodized in the memoir, “Anyone who hasn’t been in the Chilean forest doesn’t know this planet.”

The trail was steep, but the horses were sure-footed climbers. The one thing that made Miti Miti nervous was standing water. At every puddle he would tentatively paw the surface until I kicked his sides. Then, reluctantly, he would plunge in, sometimes sinking to his hocks, the mud sucking at his hooves.

After a few hours, the way grew level and we emerged from the forest into the open. Suddenly, the Yosemite comparisons were all too apt. There, on either side of us, stood domed granite walls rising a thousand meters off the valley floor, waterfalls like silver ribbons coming down the faces. In the valley was a wide meadow, a river twisting through it.

There were no rangers or entry gates. In fact, the Cochamó Valley is still privately owned, which means it is also threatened by would-be road builders, dam builders, and other so-called agents of progress. But then, neither were there mobs of tourists or traffic jams. To visit Yosemite Valley in summertime is to understand the phrase “loved to death.” Cochamó, by contrast, was blessedly empty.

Off to one side of the meadow was a broken-down barn, and next to that, a rough-hewn house like a homesteader’s cabin, with a padlock on the door. Fabián produced a key; he knew the man who’d built the cabin. We had packed tents to sleep in, but the rain was now coming down like nails and it was nice to have a roof overhead. Before long we had a fire crackling on the bare earthen floor. There was no chimney. The smoke rose up through the rafters and spilled out from under the shingles.

We changed into dry clothes and hung our wet stuff to dry. Fabián boiled water to make mate, producing from his bedroll yerba mate, sugar, metal straw, and mate gourd. It was all he carried—that and his knives: a machete; a large pocketknife; and a longer knife, like a ten-inch chef’s blade, that he kept in a sheath tucked into the back of his pants. The machete, in particular, caught my attention because it was modified from the standard form, truncated by perhaps a foot and angled downward to a sharp point at the end instead of the usual upward curve. The shortened blade was lighter, he explained, and easier to stop. You were less likely to slash your horse with it.

“And the point,” asked Jim, “what’s that for?”

“In case a horse breaks a leg and has to be killed.”

With little else to do, I grabbed my notebook and pen and began sketching the interior of the cabin—the fire, the half-burned candles jutting from wine bottles, our boots drying by the fire. I studied Fabián’s hat and poncho, smoking in the rafters. Pedro leaned in to watch. “I thought you were a writer,” he said. “That’s not writing. That’s drawing.”

Fabián guffawed. In truth, he was always laughing at us—at our ridiculous amounts of gear, at our bad Spanish, our lack of facility with the horses—not so much out of meanness, I think, as wry bemusement. We struck him as odd, and odd is funny.

With Pedro still watching, I turned the page and scribbled a couple lines, then held up my notebook. “Listen, Fabián, here’s what I wrote: ‘The smell of smoke is the perfume of the huaso.’ What do you think?”

“No.”

“No?”

“No. Better to say, ‘the smell of horse.'”

Next morning the sun broke through the clouds, but only briefly; long enough for me to snap some shots of the rime-encrusted rock faces looming over the treetops and gleaming in the morning light.

Then, after downing some breakfast gruel, we hiked to the nearby Rio La Junta, where a wide curtain of water spilled down a slab of gently sloping granite into a deep pool. A natural waterslide! Only Fabián was wise enough to forgo the thrill. The rest of us stripped to our shorts and took the plunge. Once was enough. The shock of the cold was like a boot to the groin.

As we stood shivering at the edge of the pool, Pedro, who had formerly worked as a ranger in Torres del Paine, the crown jewel of Chile’s national parks, looked around and asked, “So, what do you think: Is it really like Yosemite?” It was, I said. Remarkably similar, with the major difference that we were standing in rainforest, whereas the real thing was nestled in the comparatively dry and mild Sierra Nevada, the so-called Range of Light.

There was a longish silence, and then he said, “Pat, you have to change your report. Cochamó is not the Yosemite of Chile.”

“No? What is it?”

“Cochamó es Cochamó.”

Less than a week later I would be back home, and Jim, who had earned a month-long break from his medical residency, would be hiking in Torres del Paine. But before we parted ways, we made a quick trip to the island of Chiloé, where we drank Pisco on the waterfront and ate hearty soups heaped with clams and sausage, corn and potatoes. In the market, I bought a yarn doll and a little knitted sweater.

The fishing in Cochamó had been a bust, so we tried on Chiloé, catching a bus to a lake in the middle of the island. There, we rented an old rowboat from a drunken man who was feuding with his wife, the two of them shouting insults back and forth between the cabin and the lakeshore.

On the lake, we took turns. One of us rowed and bailed while the other fished. Between casts, Jim tried to ease my anxieties about impending fatherhood. In so many words, he said the past is always a closing door. As he saw it, nothing was really ending. I was just heading into a kind of bottleneck; life’s possibilities would narrow for a while, but soon enough, I’d come out the other side, like a rider emerging from a dark forest.

Before we rode out of the valley that last day in Cochamó, I grabbed an old, bent horseshoe I found lying in the grass and put it in my pack. Five months later, when my daughter, Lucia, was born, I nailed it over the door to her room. Eight years later it’s still there, still catching good luck for her and serving as a reminder, for me, of all life’s miseries, fine and pleasant.