Frank Warren still gets a lot of mail from strangers. The postcards in his mailbox keep coming from different zip codes, but none have a return address. They are confessions: of infidelity, of depression, of embarrassing habits. And they are all anonymous.

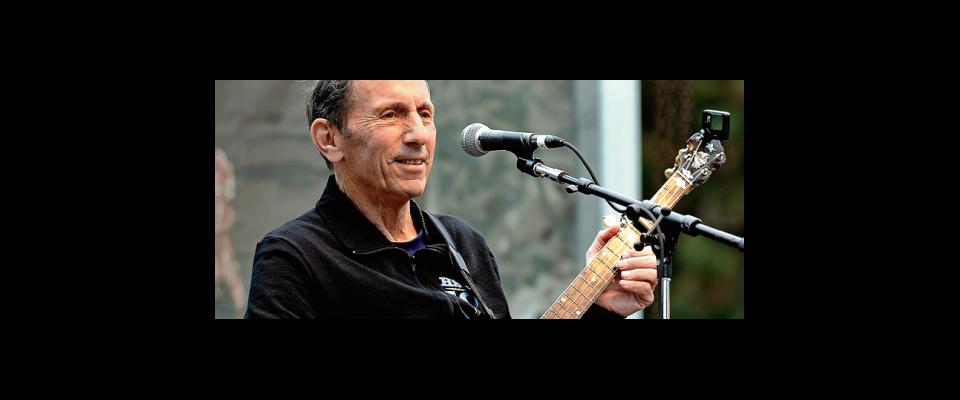

It started in 2004. Warren, who earned a social sciences degree from UC Berkeley and owned a document delivery business, conceived a public art project he called PostSecret. He printed and distributed thousands of blank postcards, asking recipients to write down a secret they had never told anyone and mail it anonymously to his home address. Only a fraction of the cards made their way back to Warren, but he received enough to display them.

Then, something odd happened: The secrets kept coming. Warren turned to the internet to share his postcards, and began posting new submissions to a Blogspot page every Sunday. As word of the project spread through cyberspace, Warren soon found himself inundated with postcards.

A decade later, PostSecret.com is going strong and the onslaught hasn’t stopped. He receives a bundle of them every day, and the sheer volume of mail that pours into his mailbox means that most of his readers’ secrets go un-posted. In fact, less than 2 percent of the postcards make it onto the website. As for the rest?

“I’m looking at a pile of a half-million right now,” Warren says nonchalantly. “It’s a pyramid taller than me.”

He’s calling from his house in Germantown, Maryland, the repository of secrets whose address is scrawled on each of those postcards. By Warren’s calculation, the pyramid in his house accounts for half of the half-million the postcards he’s received. He has kept every single one.

Editors’ note: Beginning in August of 2015, a new Smithsonian Postal Museum exhibit is showcasing 500 of the most provocative. half-million confessional postcards mailed to the Berkeley alum who’s curated them into the online sensation PostSecret. To date PostSecret has attracted more than 700 million visits from readers who come to gawk, revel, relate or empathize.

The PostSecret website, still refreshed each Sunday, bills itself as “the largest advertisement free blog in the world”—with nearly 700 million visits.

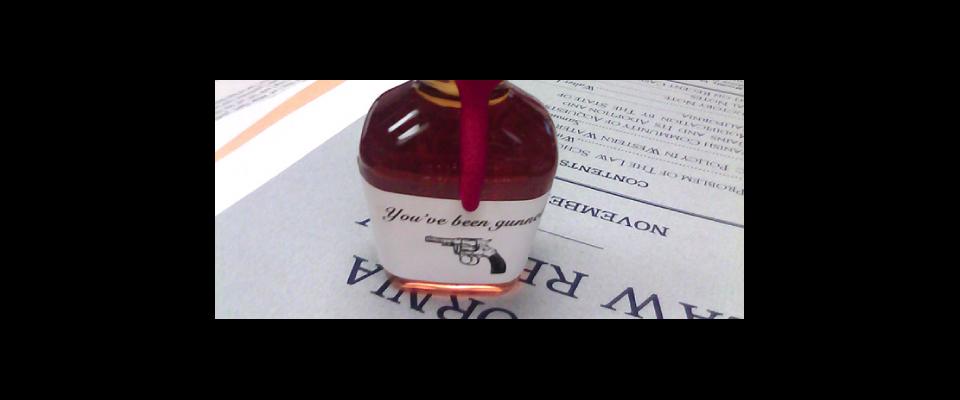

Among them: a colorful photograph of a piñata with the note “One time I got so mad at my husband that I went out to the garage and beat up my son’s birthday piñata and then told him that daddy accidentally ran over it;” a black-and-white shot of an empty classroom with the inscription “Every day I am asked to be a magician in a world where magic doesn’t exist;” and a collage of autumn leaves from an apparent Mormon missionary-in-training that confesses “I’ve been addicted to pornography since I was 12. I leave on my LDS mission in 6 months. This is my cry for help.”

Warren has an easy, offhand manner that belies his status as the confidant of a million people. Reflecting on the past decade, he recalls the chaos of getting the project started. “It turned my life upside down,” he remembers. “I sold my business and I spent probably forty or fifty hours a week on secrets.”

He has gone on to publish a series of PostSecret books—hardcover volumes full of selected confessions—and given a TED Talk about his experiences. Among the Myspace generation, PostSecret is a household name.

It’s also a magnet for controversy. PostSecret got a nod from the TV show CSI in an episode in which investigators connected a murder victim to “SecretsU,” a shadowy website. Then last year, life imitated art in a bizarre turn of events: A postcard appeared on the website showing a location on Google Maps. Written over it were the words, “I said she dumped me, but, really, I dumped her (body).” After PostSecret fans identified the location as Chicago’s Jackson Park, homicide detectives descended on the scene, although they ultimately found nothing. Warren received a call from the Chicago police, and he says it’s not the first time law enforcement has contacted him over secrets revealed on the website.

What happened in Chicago was a reminder, however grim, that PostSecret hasn’t lost its relevance. Warren is astonished by PostSecret’s longevity, and calls it “maybe the most amazing thing about the project.” He acknowledges a certain serendipity in the success of the site, brought on by a shift in technology and culture: “If you look at what young people are sharing online, it’s nothing like what their parents shared in the previous generation. I think PostSecret rides the wave of this new kind of confession that’s happening among young people that you can see in places like Facebook.”

Still, Warren says the secrets themselves haven’t changed much. “I get postcards from different continents in different languages sharing the same secret or story,” he says.

What has changed is Warren’s relationship to his secrets. Over the years, he has become an advocate for openness, touring the country and speaking about his experiences, frequently on college campuses. His presentations are multimedia experiences: Warren shows “banned” postcards, deemed too risqué to print by his publishers, and invites audience members to come forward with their own secrets.

“All of us have a secret that could break your heart,” says Warren.“If we could remember that and really know that, I think there would be more understanding and more peace in the world.” To this end, Warren has teamed up with crisis hotline 1-800-SUICIDE to create a network of phone operators on college campuses.

And he has more projects up his sleeve. He has a new book, a continuation of the PostSecret book series, as a PostSecret play five years in the making that he calls it “a fully immersive experience.” There’s also the chance that PostSecret could get its TV debut. Warren is currently developing a series that would explore the role of secrets in connecting the lives of seemingly disparate people. He envisions the show, which he recently pitched to studio executives, as a series of vignettes, and likens it to the romantic comedy Love Actually.

In the era of whistleblowers, WikiLeaks, and the NSA’s PRISM, secrets are as in vogue as ever. Frank Warren doesn’t see the well running dry anytime soon.“I think secrets are inexhaustible,” he says. “Every generation will have a deeper level to dig beneath.”