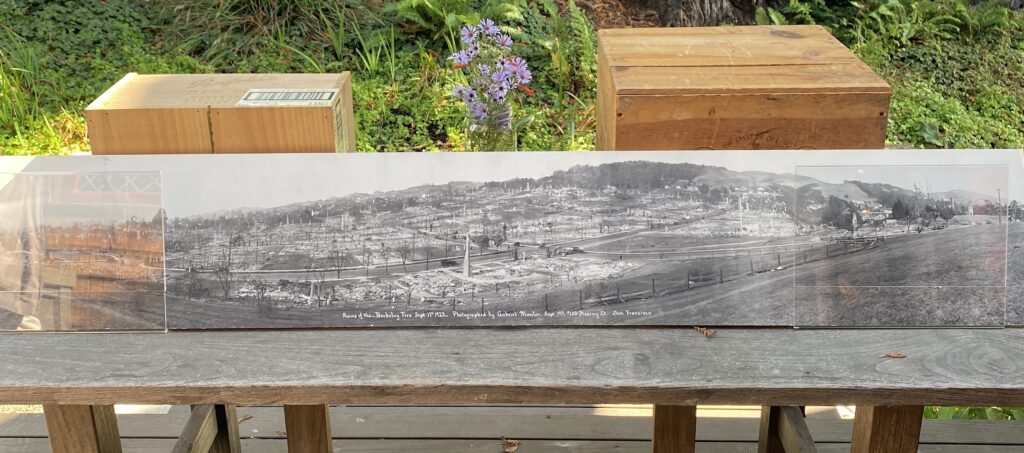

Next month will mark the 25th anniversary of the Oakland Hills Fire, the epochal conflagration that started on October 19 and, driven by strong northeasterly winds, burned more than 1,500 acres over three days, killing 25 people and destroying some 2,500 homes and 400 apartments.

Anyone who lived in the Bay Area at that time will recall the massive column of smoke that rose from the East Bay during the day and the walls of flame that limned the topography of the hills at night. Those three days felt nothing short of apocalyptic.

Before the fire, the residents of the hills had lived like lotus eaters, secure in their houses along the bosky, shaded streets. But the luxuriant trees and shrubs—mostly decorative nonnative “exotics”—that made their lives so pleasant were also highly flammable, and often grew right against the walls and eaves of the homes. In retrospect, one of the most disturbing things about the fire was that so few people had recognized the imminent danger.

Today, the 1991 burn zone has been largely rebuilt, and vegetation issues are less troublesome than before the fire; considerable effort has been expended since that time in creating and maintaining what fire fighters call “defensible space,” that is, developed zones largely devoid of flammable vegetation.

But outside the burn area?

“North and south of the fire perimeter, it’s basically like it was in 1991,” says Scott Stephens, a professor in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management and one of the West’s foremost wildfire researchers. “There are very heavy fuel loads right next to homes and other structures. The bottom line is that the fire hazard in the East Bay Hills remains very high to extreme.”

Not surprisingly, this isn’t a recent realization. Between 2005 and 2010, UC Berkeley, the City of Oakland, and the East Bay Regional Parks District applied for federal grants for East Bay Hills fuel reduction; ultimately, $5.67 million was authorized by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) for disbursement through the California Office of Emergency Services (OES). Berkeley’s share of the money amounted to $640,000, and was earmarked for treating 800 hillside acres owned by the university, much of it covered in highly volatile and non-indigenous eucalyptus, Monterey pine, and acacia trees.

“We were going to start work this fall,” says Stephens. “We had our contractors lined up. We were ready to go. Then last week, we heard that FEMA was pulling our funds.”

Scott said FEMA offered no explanation, and a spokesperson for the university’s real estate division confirmed that the agency provided no reason for the decision. Email and phone queries to Robert McCord, chief of the hazard mitigation assistance branch for FEMA’s Region 9 (which includes California), were not returned.

But if FEMA is keeping mum, it’s clear the agency pulled the funds due to a legal settlement with the Hills Conservation Network, a Claremont Canyon group that opposed wholesale fuel reduction. “We began discussions with the [U.S.] Department of Justice [which handles legal cases for federal agencies] several months ago,” says Daniel Grassetti, president of the Hills Conservation Network, “and we all agreed that the FEMA would defund the UC and Oakland projects, but would continue funding the East Bay Parks project.”

Grassetti says his group opposed the Cal and Oakland projects because they involved the wholesale removal of tall trees, a process, he says, that would be environmentally devastating and aesthetically appalling.

Furthermore, Grassetti says, “the documents submitted to the court proved that you could achieve equal or better risk reduction by focusing on removal of ground fuels and reducing the ‘fire ladder’—taking out lower branches and thinning stands of trees so you don’t have heavy rungs of fuel reaching into the canopy.” Under the original plans, Grassetti says, 400,000 trees would have been felled. “We don’t have to clear-cut the East Bay Hills to achieve equal or better risk mitigation.”

Grassetti’s view, however, is not only opposed by Stephens and other university wildfire and wild land ecology pundits. The Sierra Club also favors aggressive removal of exotic trees from the hills, as does the Claremont Canyon Conservancy, a local group vociferously opposed to Grassetti’s organization. Last year, both groups sued FEMA over proposals for an East Bay fuel reduction plan that did not include the complete removal of eucalyptus and other highly flammable exotic vegetation.

“There are multiple benefits to removing these trees,” says Scott. “We greatly reduce wildfire risk, but we also improve wildlife habitat. We’re able to bring back native oaks, redwoods, madrone and laurel, and the native understory plants. We expand opportunities for native wildlife.”

Indeed, the original fuel reduction plan is closely linked with an ambitious effort to expand habitat for the endangered Alameda whipsnake, Scott says. The university had to obtain an “incidental take permit” from the U.S. Department of Fish and Wildlife in case some of the rare snakes were killed in the fuel reduction process. Any such potential mortality, Scott notes, would be offset by the expansion of whipsnake habitat resulting from the project.

Scott says the benefits of fuel reduction can be seen by driving through Claremont Canyon.

“About seven or eight years ago, we treated a small area on one side of the road,” he says. “We removed all the exotic trees, mainly eucalyptus. Today, it’s all native. It’s ideal wildlife habitat, especially for whipsnakes. Directly across the road is untreated woodland. It’s basically solid eucalyptus. It’s an incredible fire hazard, and it has minimal wildlife value.”

But Grassetti maintains there’s too much emphasis on favoring native trees over introduced species, at least where the East Bay Hills are concerned. The tall nonnative trees, he insists, do support wildlife. Numerous species of native birds nest and forage in them, “and they’re especially important for raptors. A primary reason we have such healthy populations of hawks and owls in the East Bay is because of the tall trees—most of which, let’s face it, are eucalyptus. It gives them places to breed, and vantage points for hunting.”

“These trees shed massive amounts of bark each year, which accumulate both on the ground and along trunks and branches. When a big fire gets going, you get these huge updrafts of hot air that send big chunks of burning bark high into the atmosphere. This can start spot fires as far away as 25 kilometers.”

Further, he says, eucalyptus is no more flammable than many native species. “If you talk about volatile oils, California laurel is worse than eucalyptus,” he says.

Stephens dismisses that contention out of hand, pointing to a recent report from Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation that concluded “ribbon bark” eucalyptus—otherwise known as blue gums, the most common eucalyptus in the East Bay Hills—are extreme fire hazards.

“The CSIRO is equivalent to our National Science Foundation,” Stephens said. “These trees shed massive amounts of bark each year, which accumulate both on the ground and along trunks and branches. When a big fire gets going, you get these huge updrafts of hot air that send big chunks of burning bark high into the atmosphere. Their researchers determined this can start spot fires as far away as 25 kilometers.”

Stephens acknowledges bay trees do contain volatile oils, but says their potential for “spotting” is not comparable to the eucalyptus. “At most, bay trees may start spot fires a kilometer or two away,” he says. “That difference in distance will often be the difference between a controllable situation and complete catastrophe.”

In short, Stephens is sure that the vast stands of eucalyptus, Monterey pines, and acacia gracing the East Bay Hills are poised to burn as ferociously as they did in 1991. Further, he says, the recent cancellation of the FEMA grant closes the door for any effective fuel reduction action for the foreseeable future.

“The big problem is that the Environmental Impact Report authorized by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service expires with the funding,” he says. “Any new fuel reduction proposal will require a new EIR, and that could take years for approval. We’re in a real bind.”

Cal administrators are standing foursquare behind Stephens, perhaps presaging a long legal tussle. On September 16, university counsel Shiraz Tangri sent a letter to FEMA’s director, Jeffrey Lusk, declaring the withdrawal of the fuel reduction grants was “…illegal and improper.”

Tangri maintained that the documents authorizing the grants could only be legally abrogated with the university’s approval. If FEMA does not direct the California Office of Emergency Services to release the money immediately, Tangri warned, “The University will consider all available legal options and remedies….”

The Hill Conservation Network’s Grassetti, meanwhile, remains steadfastly opposed to the university’s plan. “Ultimately, we have to acknowledge that we have a stable, thriving ecosystem here, and the tall trees—of whatever species—are the anchor. If you cut them down, yeah, you’d have a new equilibrium in 20 or 30 years. But it would be different, and the period of readjustment could be really ugly.”