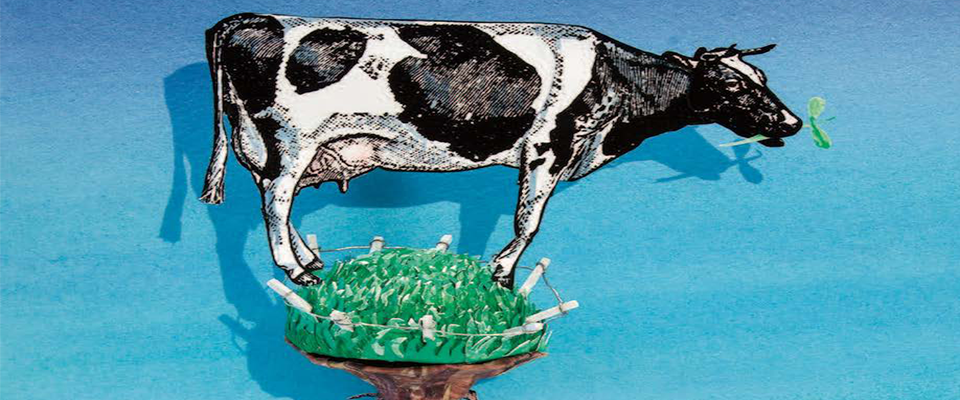

That Wagyu porterhouse makes any carnivore salivate, but tasty as many people find it, there’s no doubt that meat exacts a price both on human health and the environment. A number of studies confirm links between red meat consumption and disease, including extensive research in Britain and Germany concluding that vegetarians are 40 percent less likely to develop cancer than carnivores. And industrial meat production affects the planet in a variety of unpleasant ways, from massive atmospheric carbon emissions to widespread contamination of waterways.

And yet, U.S. meat production remains a $1 trillion enterprise; it’s not going to disappear anytime soon. But any number of meat eaters might be induced to consume less animal protein—and improve both their own and the planet’s health— if they had a good alternative to In-n-Out animal-style burgers or that succulent rack of baby backs from the local rib shack. Trouble is, “meat alternatives” are long on the alternative part and short on desirable meaty characteristics. They mostly run to rubbery pucks of indeterminate vegetable material or “sausages” that burn but don’t brown and emit off-putting aromas reminiscent of an active compost pile. They simply don’t make it in the taste, aroma, and appearance departments.

Some start-ups have produced “guilt-free” real meat cultured from domestic animal cell lines, but it’s unclear if consumers are comfortable with the idea of test tube hamburgers, and the process is expensive—far too pricey at the current stage of development to be anything other than a boutique curiosity for the well-heeled and gastro-curious.

The first step in weaning people off pork roasts and rib steaks in a wholesale fashion is giving them something they want to eat, something that may not taste like meat, but satisfies like meat. Judging from the products that are out there, however, that seems easier proposed than done. So the faculty at UC Berkeley’s Sutardja Center for Entrepreneurship and Technology decided to unleash some brilliant undergrads at the problem, launching a Challenge Lab on alternative meat products. This is the course’s second semester, says the lab’s co-director and Sutardja visiting professor Ricardo San Martin, and in terms of student and corporate interest, at least, it’s a success. Enrollment is up to 50 students from 35, and Givaudan, a Swiss firm that specializes in developing fragrances and flavors, is supporting the project.

Further, Givaudan has given the current lab a goal: the development of a plant-based product that has intracellular fat and water, like real meat. Creating such a product would be like finding alternative meat’s Holy Grail, in that one of the foremost complaints about existing ersatz meats is their lamentable “mouth feel.” When real meat is masticated, the rich umami flavors of various lipids and amino acids are released as the cellular walls of fat and muscle fiber are breached. Not so, of course, with bogus burgers, which merely go “squish” as you chew them, rather like a sponge infused with artificial flavors.

“There already are a lot of start-ups in this space, but we’re really at the infancy of the sector. A lot of fundamental research remains to be done, and not just on the palatability of the products. We also have to be able to hit price points.”

But creating such a product is going to be a heavy lift, acknowledged Peter Cnudde, the vice president of engineering for Yahoo and a member of Sutardja’s advisory board. Cnudde sits in on the lab sessions, compelled by a deep personal interest in abating the animal suffering and environmental impacts of commercial meat production.

“There already are a lot of start-ups in this space,” said Cnudde, “but we’re really at the infancy of the sector. A lot of fundamental research remains to be done, and not just on the palatability of the products. We also have to be able to hit price points. Chicken isn’t popular just because people like the taste. It’s also cheap. Commercial chicken is industrial chicken, produced on a massive scale. The techniques are well-known. We’re going to have to demonstrate that kind of scalability with any kind of alternative meat product that passes the taste test, or it will just remain a specialty product, one that won’t make any significant inroads into the meat sector and therefore won’t have any impact on the negative impacts of meat production.”

Last semester’s lab developed two proto-products: an extruder that could be used in the production of alternative meat materials, and a plant-based “fish.” Neither has been perfected, said San Martin, but the students who developed them haven’t given up.

“They feel they can still do it,” he said.

At a recent lab session, San Martin emphasized the daunting dimensions of the undertaking, observing that the development of a new and potentially disruptive product involved storytelling.

“It’s important that we understand the story we’re trying to tell,” he said. “[The story] is how people are seduced into moving from one place to another.”

That said, he continued, alternative meat was challenging because acceptance of such products, no matter how savory, was not automatically assured, even among the well-educated, whom, it could be assumed, had a pretty good handle on meat’s drawbacks.

As evidence, he cited a survey conducted among last semester’s students on their basic views of alternative meat. Of the 34 students queried, 16 were “skeptics” who were largely resistant to alternative meat, but “thought it’d be okay for vegans.” Twelve students supported alternative meat in theory, but with reservations: Product lines needed to be improved dramatically over existing brands. Only seven gave the whole idea an unqualified thumbs-up.

Then San Martin, whose expertise is chemistry and biology, addressed the technical issues confounding alternative meat development. He riffed a bit on soybeans, the main feedstock for current products.

“The first thing that’s done is the oil is removed by a complex chemical process,” he said. “Then you extract a protein isolate that you subject to an extrusion process. It’s an old technology, and difficult to scale. So you end up with a spaghetti-like product that you have to flavor and treat with preservatives, and turn into chicken strips or whatever, and then it has to be frozen. So you have to ask yourself if this is the best we can do. It’s clear to me that it’s hitting a wall.”

San Martin said that the basic approach to alternative meat should be reconsidered, noting the design of flesh-like matrices from the molecular level up is a more likely way to satisfy Givaudan’s challenge than extrusion processes.

“And it’s not just a matter of achieving a desired fat/protein ratio,” he said. “The type of structure is critical, and that has to be engineered, [with due attention paid to] chemical and molecular bonding. We need to be able to measure and quantify molecular properties, not just of texture and structure, but of flavors, color, and aroma. And we need to determine the best plant-based materials for doing this, which means looking beyond soybeans. Mung bean isolates, for example, have gelation properties similar to scrambled eggs. Fungi are a possibility. And algae might be useful, though there are taste issues with algae that have to be overcome.”

Both Cnudde and San Martin championed the investigation of natural processes such as fermentation that could augment or supplant nano-engineering techniques.

“Nature also has a propensity for self-assembly, especially at surface interfaces,” said San Martin. “Tofu skin is an example. It self-aggregates on the tops of vats during the tofu-making process, and is a valuable product in its own right. So this could be a way forward in [alternative meat] development.”

Judy Savitskaya, a Cal PhD candidate in bioengineering, talked to the class on the basic nature of proteins, noting that their physical properties are largely determined by the way they “fold.” That’s essential when considering meat—or alternative meat—because proteins that fold to create long fibers and sheets are tough and largely insoluble, and comprise things that include collagen and keratin. Globular proteins, on the other hand, are soft and soluble in water.

“Food proteins tend to be globular,” said Savitskaya. “Examples are casein [in milk] and albumin [in eggs]. They’re relatively easy to digest.”

“If it’s not delicious, people won’t eat it and they won’t buy it. When you’re talking about meat or meat substitutes, you’re basically talking about umami, and nothing does umami like a good steak.”

Alternative meat developers might therefore be well advised to include lots of juicy globular proteins in their formulations, but they also shouldn’t reflexively reject all stringy proteins. After all, proteins such as actin and myosin are fibrous and plentiful in muscle tissue, said Savitskaya, and “give [meat] its stretch and pull.”

Flavor and aroma can also be affected by protein folding, said Savitskaya, particularly if various carbohydrates are incorporated in the folding process. Further, both texture and flavor are altered by heat, e.g. cooking, so that has to be taken into account in formula design.

In short, it’s a lot to heap on a single plate. Indeed, it may be too much. Maybe the goal of making synthetic plant-based meat analogue with a structure and taste that satisfies like a real T-bone is just impossible to achieve. Maybe we should be looking at another model: not round steak, but ground round.

That, certainly, is the opinion of Bruce Aidells, who also spoke at the recent lab session. Aidells is a former endocrinologist who took his doctorate in biology at UC Santa Cruz, worked under Cal molecular biologist and Nobel laureate Donald Glaser, and participated in extensive studies on breast cancer. But while Aidells is renowned, it’s not for his research. The founder of Aidells Sausage Company, he’s a bearded, droll, Falstaffian figure who is something of an ambassador for good living in general and the preparation and consumption of high quality meat particularly. These days, he spends much of his time authoring cookbooks—such as the seminal Complete Meat Cookbook and subsequent Great Meat Cookbook—and noshing at Prospect and Boulevard restaurants in San Francisco, both owned by his wife, Nancy Oakes.

“The great challenge for alternative meat is to make it delicious,” Aidells said. “If it’s not delicious, people won’t eat it and they won’t buy it. I have nothing against vegetables. I love them. But when you’re talking about meat or meat substitutes, you’re basically talking about umami, and nothing does umami like a good steak.”

Aidells advised the students to think sausage and ground meat, not New York strips.

“The architecture of fibrous muscle is incredibly difficult to reproduce,” he said. “I’m not sure it’s worth the effort. I don’t think you should challenge yourselves too much. It’s better to produce something that satisfies meat eaters but doesn’t ‘pretend’ to be meat, and ground products let you work toward that goal. Binders like agar and other natural gels let you incorporate compounds that are truly delicious and satisfying. Going the ground product route would also allow you to scale, to get to the price points you need to succeed in the market.”

San Martin was compelled to pose a question to Aidells at that point, asking how it would be possible to avoid the “filler” pejorative with a ground product. Aidells responded with San Martin’s own storytelling trope.

“It’s about the brand, not the recipe,” Aidells said. “You have to tell a good story. Is it a marketing challenge? Absolutely.”

Indeed, Aidells didn’t seem particularly enthralled by the concept of alternative meat, delicious or not.

“After this, I’m going back home to cook lamb chops,” he told the class. Many of the students seemed to relate.

“What’s the best place in San Francisco to get a good steak?” one of them asked.