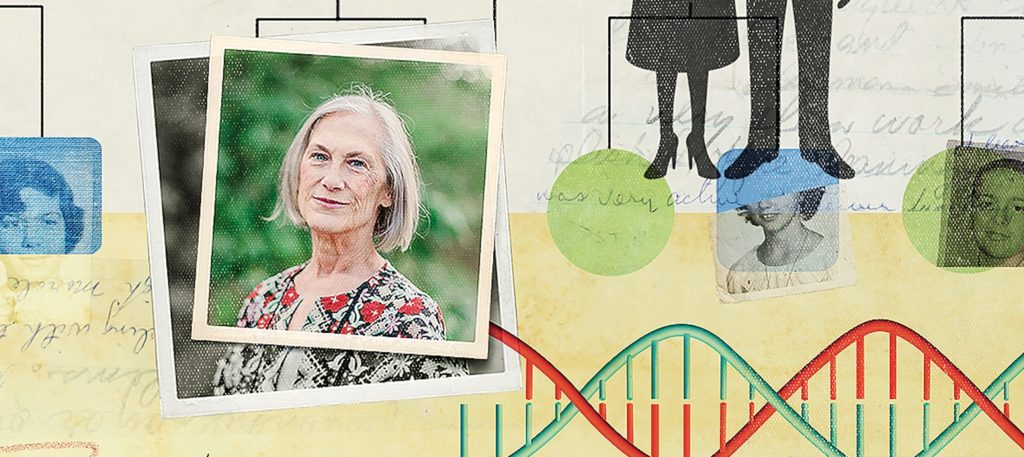

Bailey Farren grew up in Petaluma, the daughter of a firefighter father and a paramedic mother. She became acutely aware of the hazards of both trades at an early age.

“When I was 7, my father was blown off a roof by a master stream [an extremely large hose and nozzle] and was seriously injured,” Farren recalls. “My four brothers and I visited him in the hospital, and that was when we realized Dad had a very dangerous job. Later, when he’d be go off to big fires on strike teams, our mother assured us he was safe, that he was OK. But we knew he always faced real danger.”

Farren and her siblings were schooled at home, where they learned survival skills like “situational awareness”: knowing where you are in your environment at all times—and how to respond accordingly.

In the aftermath of the North Bay fires, Farren started to wonder: Could there be a better way to track fires and identify escape routes?

“My parents were always giving us messages about staying alert and focused, messages that other kids didn’t get,” Farren says. “They lived by that code because they were always among the first members of the community to respond to a crisis. I remember one time my brothers and I were in a minivan coming from In & Out and there was an accident right in front of us. My mom immediately stopped, set out flares she always kept in the van, and started directing traffic.”

Everything changed in October 2017 when the Tubbs Fire raged through Santa Rosa, killing 22 people and destroying 5,600 homes. Farren—who was studying data science and rhetoric at UC Berkeley—and her brothers had to drive to northeast Santa Rosa and evacuate their mother from her home on Brush Creek Road not far from Fountaingrove, an upscale development that was utterly immolated. Though her childhood home survived, Farren knew that other homes—and lives—weren’t so lucky. In the aftermath of the catastrophe, she started to wonder: Could there be a better way to track fires and identify escape routes?

“I spent a lot of time during the year following the Tubbs Fire interviewing evacuees and first responders, and I realized there was a huge gap between the technology Silicon Valley was developing and the [informational] tools firefighters had,” Farren says.

During the following year, Farren joined forces with several other Cal alums—including Trevor Greenan, who lost his family home in the Tubbs Fire—to develop Perimeter, a fire modeling and simulation platform. It integrates satellite-generated information and images with data on weather, terrain, road closures, possible evacuation routes, and suppression resources—all in real time, with rapid refresh capability. The platform is undergoing beta testing through the current fire season.

Farren and her partners believe their technology will change the game for emergency fire response, but they aren’t without competition. Fire modeling platforms in one form or another have been around at least since the 1980s, says Berkeley mechanical engineering professor Tarek Zohdi.

“I write software for these programs myself, and I know they’re being sponsored all over the country,” says Zohdi. “This is a large domain, and all of [the platforms] share a basic goal—to get information to first responders as fast as possible by interfacing with satellites and sensors on the ground, and coordinating the data.”

Currently, most models are employed by upper-level fire management supervisors who use the data to formulate broad strategies during fires. Perimeter wants to democratize that process, allowing both line firefighters and fire victims to download critical information through cell phone apps and upload their own information, creating an interactive data and communication network.

Mark Finney, a Forest Service research forester who completed his Ph.D. at Berkeley and developed FARSITE, a seminal fire modeling platform, is intrigued by the crowdsourced aspects of Perimeter—but he also sees a potential logistical problem: cell coverage.

“A basic issue with any model that depends on a mobile app is coverage,” says Finney. “You may not have good cell coverage on wildfires because they’re often in steep, remote terrain.”

Farren says Perimeter’s primary application won’t necessarily be in remote wilderness areas where cell coverage is scant or nonexistent, she says; rather, it will be in the wildland-urban interface (WUI)—zones where wildlands and homes adjoin, and where the threat to human life and property is greatest.

“What sets Perimeter apart is both her motivation and the beneficiaries. For her, the big thing isn’t making money. She wants to help first responders. People like her parents.”

“Mobile coverage is usually good in the WUI,” Farren says, “but we’re also aware that coverage in general is a legitimate concern. So we’re developing a peer-to-peer technology that uses Bluetooth to bounce data up and down the fireline—you don’t need the Internet.”

Like any new app, Perimeter could either catch fire or gutter out. And the critical difference may be marketing, acknowledges Farren, who is a dynamo when it comes to promoting her product with venture capital firms, fire agency supervisors, and Cal professors.

“It probably all goes back to my parents,” she says. “They encouraged us kids to try random projects and run with them. I started a baking venture with a friend when I was 10 years old, and we did really well. I learned how to sell hard with that project.”

Shomit Ghose, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist and lecturer at Berkeley’s College of Engineering, thinks that pitbull attitude may give Farren an edge over the competition.

“I got to know her when she was the TA for a class I taught last year,” says Ghose. “She’s got a visceral and emotional drive that is qualitatively different from someone who says, ‘Oh, that looks like a potentially big market—let’s get in.’ A lot of people are in this space, but what sets Perimeter apart is both her motivation and the beneficiaries. For her, the big thing isn’t making money. She wants to help first responders. People like her parents.”

During her second year at Berkeley, Farren worked in technical sales for a data analytics company in Sunnyvale. At one point, she identified what she thought was the perfect firm for her company’s product. She deluged executives with emails and called them nonstop, but was essentially ghosted.

“They’re in Los Angeles, and I finally got so frustrated at the speed of the turnaround responses that I drove down the day before Thanksgiving, went into the building, and just started knocking on doors. And before the day was over, I made the sale. And I’ve brought that ethic to Perimeter. I’m literally working 70-hour weeks. I’m not getting paid a cent at this point. And there’s nothing I’d rather do.”