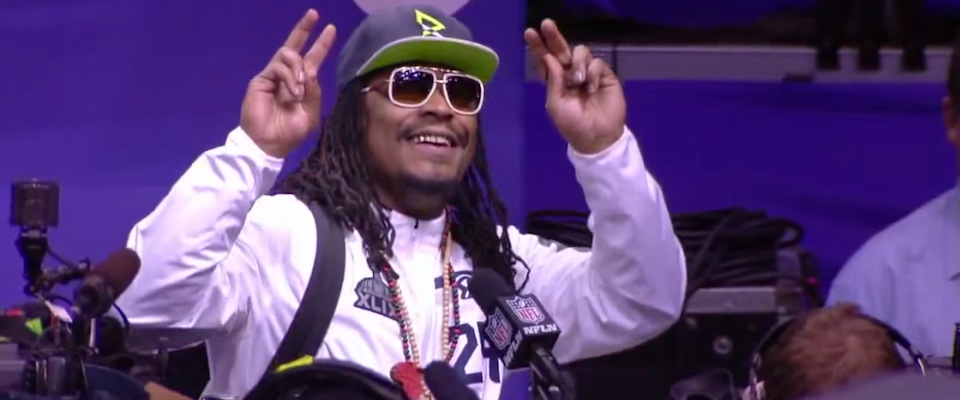

David Shields was having a good night. His new film, a biographical documentary about retired running back and former Cal phenomenon Marshawn Lynch, had just screened to a packed and enthusiastic house at The New Parkway Theater in downtown Oakland. Now he was joined at the front of the theatre for a Q&A by former UC Berkeley sociologist Harry Edwards and moderator Michael Smith, formerly of ESPN. Edwards was heaping praise on the film, entitled Lynch: A History.

“This is the fifth time I’ve seen this film, and I’ve never seen the same film twice,” Edwards said. “It’s really not a documentary. It’s a jazz suite.”

Shields looked as if he might tear up.

Silence is a central theme in Shields’ film because of Lynch’s famous obstinance with the media.

Shields and Edwards are both bald. And that’s about it for obvious similarities. Edwards is six-foot-eight, black, and dressed head-to-toe in black—black pants, black sweater, black skull cap, black shades. Shields, a University of Washington English professor, is a slim, bespectacled white guy, reserved in both appearance and speech. For most of the thirty-minute-long Q&A, Shields listened in rapt attention along with the theatre audience as Edwards held forth on an array of topics including police violence, Colin Kaepernick, the Negro Leagues, Jack Johnson, and his appreciation for Lynch: A History.

Watching the film, he said, “is like listening to John Coltrane. You can pick up on one theme and follow it all the way through, whether it’s the anger, whether it’s the media, whether it’s the silence.”

Silence is a central theme in Shields’ film because of Lynch’s famous obstinance with the media. In post-game interviews during his playing days, the Oakland native often answered questions with repetitive non-answers such as, “Yeah,” or “Thanks for asking,” or most famously, “I’m just here so I won’t get fined”—a reference to NFL rules regarding media appearances. Shields portrays Lynch’s silence as weighty and radical, a refusal to play by the League’s rules.

Continuing on the silence motif, Edwards shared an anecdote about a song Miles Davis once played in concert. “Miles played about six notes,” Edwards said. “Afterwards a reporter asked him, ‘Miles, why’d you play so sparsely?’” Edwards affected Davis’s slow, raspy voice: “‘You just don’t understand. The silence is a note.’” The audience laughed.

“Is the filmmaker, namely myself, making this film for a white audience? I hope not. I hope I’m making it for everyone.”

Lynch: A History is Shields’ first film project, and the results are unconventional. The entire thing is montage. No narration, no captions, just patched together footage ranging from grainy clips of a high-school-aged Lynch blowing past defenders to cellphone video of police shootings of young black men to scenes of protest in Ferguson, Missouri. That’s how the film starts, and the pace and intensity only ratchets up from there, clip after clip, often jarringly juxtaposed, to tell a story much bigger and more complicated than Lynch himself, one about race in America.

True to his brand, Marshawn Lynch declined to participate in the film.

The film is not Shields’ first project to take on the subject of race and sports. His 22 books include Black Planet: Facing Race During an NBA Season, in which he grapples with how white NBA fans, like himself, think about and talk about black basketball players.

He acknowledges the inherent thorniness of a white author interpreting the black experience. “My god, this film has gone through so many iterations, some of which involved excruciating self-consciousness about being a white filmmaker making a film about an iconic black figure,” he said on the phone from Seattle.

In fact, several minutes into the film he seems to confront the issue head-on. A young Bill Cosby appears on-screen and says of American film, “For the most part the black portraits have been drawn by white writers, white producers, and white directors for a white audience.”

“Is the filmmaker, namely myself, making this film for a white audience? I hope not,” Shields told me. “I hope I’m making it for everyone.”

“Do you ever think about Marshawn’s perspective on how he views this?” a man asked. “Everyone has an opinion about silence. This is really well put-together, but I feel like it was missing his perspective.”

He must have been delighted, then, with the New Parkway crowd. It was not your stereotypical, staid documentary audience. When news clips of Donald Trump flashed across the screen middle fingers were raised. When Lynch’s high school football coach, Delton Edwards, appeared cheers and shouts of “Coach D!” went up. And during a section of the film highlighting the many rebels and revolutionaries Oakland has given rise to—Huey Newton, Alice Walker, Tupac Shakur, Barbara Lee among them—the audience cheered and hooted.

Edwards concluded his remarks by saying of Shields, “I don’t know what my brother here set out to do, but as Miles used to say, ‘We might not have done what we practiced and intended to do, but what we did turned out alright.’”

“I can die and go to heaven,” Shields said. He explained that he’d read Edwards’ book The Revolt of the Black Athlete at fourteen years old, and has been working to meld his interests in sports and politics ever since. Sharing the stage with Edwards, he said, “is really the consummation of my life.”

But there were two screenings that night at the Parkway and two Q&As. As soon as the first ended, Shields hustled over to the theatre next door to participate in the second. Smith joined him to moderate, but Edwards had left.

“Do you ever think about Marshawn’s perspective on how he views this?” a man asked. “Everyone has an opinion about silence. People just come up with a speculation. As the media you have a responsibility. This is really well put-together, but I feel like it was missing his perspective.”

“Exactly,” a young woman added. “I want to know his point of view.”

“Of course we approached him,” Shields answered. “I would have loved to have interviewed him, but I also would have been bitterly disappointed if he would have agreed to an interview. Because his whole stance is ‘I’m just here so I won’t get—’”

“I don’t know what my brother here set out to do, but as Miles used to say, ‘We might not have done what we practiced and intended to do, but what we did turned out alright.’”

“But is that his actual stance?” the young woman interrupted. “I feel like the stance that he took was that, ‘I’m not going to be here dancing around for you guys.’ …You didn’t have the major piece. And the major piece was Marshawn.”

The first man continued, “It’s almost like, whether it’s for him or against him, you’re doing it again. Assuming and speculating. They do it all the time, with him particularly.”

The moderator stepped in, asking the commenters whether the many lifted clips of Lynch that Shields included in the film didn’t adequately represent his perspective.

“I want to get to the bottom line,” the man answered, “not another speculation.”

Shields struggled to answer before time ran out.

Editor’s note: This story has been modified from a previous version.