In a New York Times essay titled “When Science Fiction Comes True,” author and Berkeley English professor Namwali Serpell describes stories as “one of our oldest technologies.”

Stories, Serpell explains, allow us to experience the beautiful and the terrible “and then close the book, or the laptop, unscathed.” They can also give us what Serpell terms “virtual hindsight”—the ability to experience a future while still in the present, asking ourselves: Is this where we’re headed? And, perhaps more importantly: Is this where we want to go?

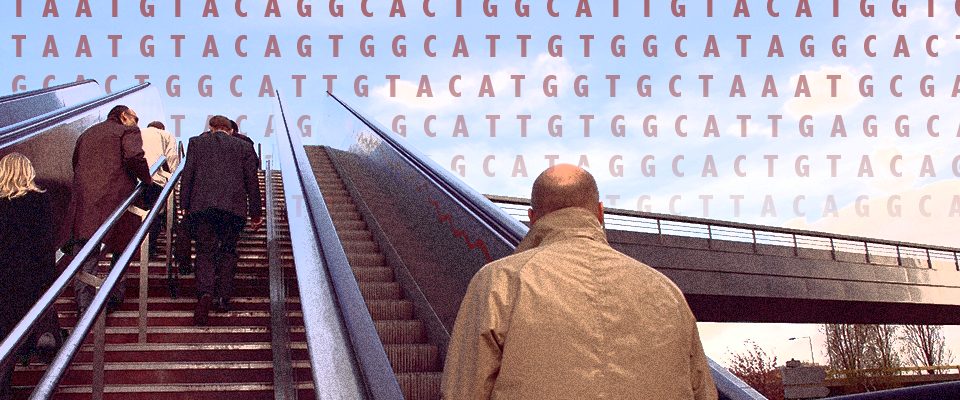

For our Winter 2019 issue, Serpell and her former student, writer Tyler King, imagined a future involving CRISPR gene editing. Their flash fiction piece, “A Mercy, A Sport,” incorporates anagrams and palindromic repeats, a reference to the final letters of the CRISPR acronym. Words in the story mirror, evolve, and reform. Cause and effect become one and the same, time taking its cue from “those spools of ciphers, those spheric loops” of DNA. Curious tinkering, at first a game, has real consequences.

As their story went to press, we asked Serpell and King to comment on speculative fiction, fate, and the process of co-writing. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What part do you think speculative fiction can play in helping us to understand and grapple with the ethical implications of technologies like CRISPR?

Namwali Serpell: Fiction doesn’t always predict the future well, but it’s quite good at exploring the subjunctive—what might or could follow from a set of events. Because it has always revolved around human psychology, fiction allows us to untangle subjective possibilities that the biological sciences—because they are keyed to objectivity and statistically predictable outcomes—overlook. Speculative fiction is another kind of knowledge. I don’t believe fiction should directly influence policy or scientific experiments, however. The social sciences—ethical philosophy, human psychology, sociology, etc.—are far better equipped to grapple with the implementation of scientific technology in the real world.

Tyler King: I think the greatest strength of fiction is its ability to pose questions to the reader, but each reader will answer those questions differently. You can’t assume that someone will draw the “correct” conclusion simply by reading a book. And as time goes on, the conclusions readers draw will shift. I think of “A Mercy, A Sport” as a kind of cautionary tale, but I can also imagine a future where it’s enticing. So I wouldn’t necessarily count on fiction to help anyone understand anything, as much as I would like to.

The collective voice of the scientists in the story is compelling and somewhat haunting. They often seem to be more amused than concerned. How did you choose the voice and tone of the story?

NS: The collective voice isn’t just scientists, to my mind. It’s members of society too—their willingness to go along with these experiments out of a sense of curiosity. The amused tone was to suggest that, like the boy, they may also have been affected by this off-target effect of timelessness. The story they tell is palindromic, redundant. They already know it, they are unsurprised. They, too, are vague and grinning.

There is an interesting tension in the story between a fate that is beyond human control—I’m thinking of the line that asks “Isn’t that how a heartbeat is scripted, and a footstep too?”—and a desire to create our own fate by changing our genes. Can you talk about this tension and the role of fate in the story?

NS: That sentence is in the voice of “hubristic humankind,” so I see it as unreliable. Humans are anthropocentric and solipsistic. They often retroactively justify “the ways of man” by pretending that they are somehow fated or “scripted.” If there is such a thing as fate, I think it appears as “irony”–as the mismatch between what we foolishly assume will happen and what actually happens. In that sense, fate is an effect, not a cause.

I was interested in the idea that our unique relationship to time makes us human. Can you speak further to the role of time in the story?

NS: Again, I think the plural narrator is wrong about this. We have no idea what a whale’s relationship to time really is. But it is a common conception that human beings are uniquely aware of time. I read it most recently in Your Brain Is a Time Machine: The Neuroscience and Physics of Time by Dean Buonomano. I was also influenced by the relationship between linear and circular time—and the idea of mapping it onto the form of a story—in Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life,” which was the basis for the film Arrival.

What was it like to co-write this story?

NS: Interestingly, this process was akin to the kind of communal work, the synthesizing of ideas, that happens in a lab. When I looked up what CRISPR stands for—Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats—I was inspired by Tyler’s incorporation of palindromes into the form of a story he’d written in my class.

TK: I’d written this maddening story called “Springhouse Surgeonship” for one of Namwali’s fiction workshops. It had a roughly palindromic form, which was simple enough to see, but the rest of it was far too demanding. About a third of the prose was almost purely anagrammatic, which made the story way too hard to read. I think I annoyed my classmates a bit with it.

NS: I think they were fascinated and intimidated! I was intrigued but had some thoughts on how to make it easier on the reader. I drafted this story with a mirrored structure and a couple of my favorite anagrams from Tyler’s story. Then we emailed back and forth about some more anagrams that could be inserted without making things too confusing. In a way, I thought up the content, Tyler the form. They are equally important to any story.

TK: I was pleased to see that Namwali had borrowed some of my favorite anagrams and that she wanted more! This story also fits the idea I had much better because the form and content are very closely aligned—I had struggled to justify what I was doing in my original story, and it never quite worked. I’m glad to see that effort pay off here.