Philip Lee ’82 was 14 when he immigrated to the United States from Hong Kong in the mid-1970s. His new high school classmates teased him, calling him Bruce Lee because of their shared racial background and last name, but Philip didn’t let this color his first impressions of his new home. “It was my first experience in America, so I didn’t know what to expect, nor think it was bad,” he recalled, “I was just so happy to be [here].”

Upon graduating high school, Philip pursued a degree at the University of California, San Diego for two years before the opportunity arose for him to transfer to Cal. “I wanted to go to Cal all along,” Philip admitted. “I knew the attraction of the academic achievements at Cal, and I knew about the social liberalism and all the activities.” Despite his knowledge and the draw of Cal, Philip’s first two weeks on campus were a culture shock.

The First Two Weeks

Berkeley, in many respects, was different from everything Philip had previously experienced. It wasn’t just the swaths of students on campus, but also the types of people surrounding him (there were so many people who looked like him, unlike his high school), the sheer numbers of challenges both large and small (making sure he got into all of his classes) facing him, as well as the volume of stimuli he encountered in and outside the classroom.

“You do it to the degree in which you want to engage,” Philip said. “I feel like I learned more outside the classroom than I did inside the classroom. When you’re at a big school, you might as well take advantage of it. I’m not a big football fan, but I love going to Cal games!” As a psychology student, Philip joined the Association of Psychology Undergraduates, but also explored a couple Asian American student organizations, KALX, and folk dancing at the International House. It was ultimately the job he found at the ASUC bookstore that led him to his closest community of friends and the path he continues to pursue today.

Philip helped oversee the women’s studies section at the bookstore during an era when feminist literature experienced tremendous growth. As a student, he didn’t have the authority to oversee which books were stocked, but he was exposed to the feminist movement and encouraged to read the titles by scholars like Susan Brownmiller and Betty Friedan that he shelved daily. “I became really aware of what [these authors] were putting out. [My job at the bookstore] gave me personal maturity and exposure. Being aware of feminist issues and international issues…shapes what I’ve done since,” Philip explained.

One of Philip’s bookstore friends had encouraged him to move to New York after Cal, so following graduation, Philip remained in Berkeley and worked in other local bookstores until he’d saved up enough money to make the move.

Reflective or Aspirational

In New York, Philip launched his publishing career at magazine publisher Conde Nast, and subsequently moved to Glamour, Vanity Fair, and then GQ, where he remained for several years in the marketing department. It was the late ’80s, when America was becoming more diverse and its population was aging. “You can see the trends, but companies in the ’80s weren’t interested in addressing diversity issues,” Philip recalled. In meetings, his coworkers asked: “Should we have magazines for women over 40?” Philip was prodded to wonder, “Do [these magazines] reflect America, or are they aspirational?”

“I loved working for that company, but I was one of the first persons of color in management, and I felt like it was important to start, as I got older, to address the social change conversation,” Philip explained. It was a conversation Philip had first entered on the Berkeley campus, but gotten complacent about addressing in the wake of his own success. “After [working at GQ for] a couple years, I returned to that Berkeley question: ‘How can I make a difference?’ And I wasn’t doing that [at GQ]. I was just having fun.”

“After a couple years, I returned to that Berkeley question: “How can I make a difference?” …I wasn’t doing that. I was just having fun.”

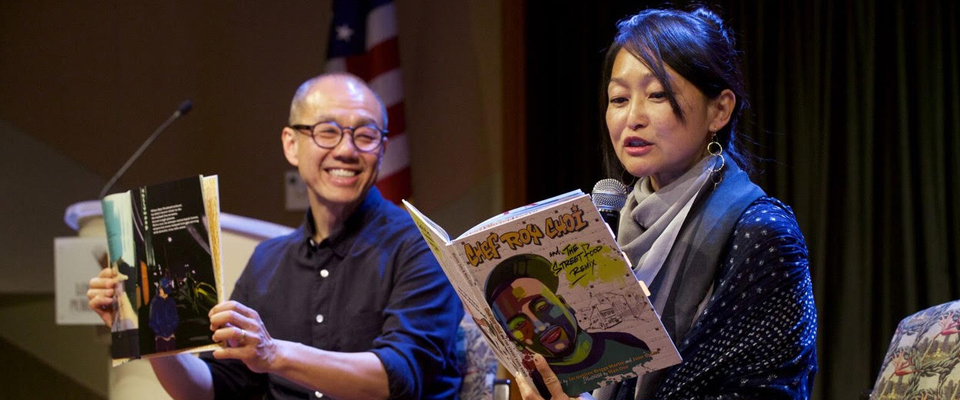

This realization led Philip to pivot his career from magazine to book publishing, founding Lee & Low Books in 1991. Lee & Low’s Books—including its most well-known title, Baseball Saved Us, which was launched into success in 1993 after being reviewed by The New York Times—found great support from teachers and librarians, and is now the nation’s largest publisher of children’s multicultural books.

For 13 years, Philip worked in this space. He focused his efforts on advocacy, working to bring books that “reflect the cultural backgrounds of children” into elementary schools and libraries across the country in hopes of addressing the growing achievement gap between children of different racial backgrounds.

When Philip sought to present his work to policy-makers and elicit change in the legislation of children’s education, the policy-makers told Philip, “The achievement gap is not a reflection of a learning problem in school, but a reflection of public health problems in school. Kids are suffering from hunger and obesity.”

In 2004, Philip was no longer convinced that his current efforts were enough. He left Lee & Low Books to more deeply pursue children’s education advocacy work. “We need to have a dialogue as a publisher not just about food, but food education,” he pressed. “Know where your food comes from, know what you’re eating. As a publisher, I want to focus on how we eat, that culture part. It’s the story behind this that changes the cultural dialogue.” With that, Philip made yet another career change in 2008 and founded a second publishing company in 2009 with his wife: Readers to Eaters.

Food Literacy

Since his days at Berkeley, Philip knew he had a certain fondness for stories. In establishing Readers to Eaters, he turned back to his roots in search of stories about food that would bring families together, both to read and to eat.

The story, Philip insists, doesn’t need to be complex nor rooted in racial backgrounds, as much of his work at Lee & Low Books had been. “You can find a story in reading a recipe or reading a food label together. Just talking about food breaks down a lot of the hierarchical structure in this country,” he explained.

Instead of focusing on race, Philip now focuses on culture. “I find the word ‘culture’—rather than race—is more inclusive, but also more specific at the same time.” He explained: he associates himself with one race, Chinese. Culturally, however, he feels a part of the cultures of Hong Kong, California, and the Pacific Northwest, where he now lives with his family.

Philip’s decision to join the food movement was well-timed. Readers to Eaters was founded in 2009, three years after UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism professor Michael Pollan’s published The Omnivore’s Dilemma, and one month after former First Lady Michelle Obama launched her iconic vegetable garden at the White House.

True to Philip’s goal, Readers to Eaters doesn’t just serve as a publisher. The Seattle-based company actively reaches out to support its community by selling books at farmers’ markets and conferences for teachers, nutritionists, and food activists, and hosts talks promoting food literacy in partnership with local organizations.

For Philip, the work of Readers to Eaters fulfills his promise to continue “carrying out the Berkeley experience.” His path has made Philip something of a pioneer, as one of the few Asian men currently in publishing, but his intention was never to lead the largest company of its kind in the industry. “My goal was to encourage 25 other Lee & Lows to dare to break into the space,” Philip said. “It makes so much difference to know things can be done.”

Philip hasn’t spent much time on the Cal campus since graduation, but he often circles back to the Berkeley experience to remind himself of the lessons he learned as a student and the importance of mentorship for the success of future Cal alumni. He affirmed, “Our experience is to remind us we can make a difference.”

by Courtney Cheng ’16