How Barbara Goodell ’68 used salsa to help women learn English.

Snack time was piquant in Boonville’s adult school. The Mexican women studied English all morning, but their grandmothers’ recipes ruled during break, and so The Secrets of Salsa cookbook was born. Ten years and 25,000 copies later, the bilingual recipe book has gone far beyond its modest ambitions of making a few bucks for a fieldtrip. These days, the book’s sales actually help support the California adult school that gave it life. More importantly, the experience has done wonders for the confidence of the women who wrote it and the cohesion of the Anglo-Mexican community in which they live.

Though many chefs contributed to the sauce, the book wouldn’t exist were it not for Barbara Goodell, an innovative and generous-hearted alumna from Cal who graduated in 1968 with a major in English, minors in anthropology and physical education, and a strong desire to be a teacher. Raised in San Rafael, she’d set her sights on Berkeley. “I don’t think I even applied anywhere else,” Goodell recalls. “Fortunately, I got in.”

Ten years later, Goodell was living in San Diego, teaching 8th grade, and writing her own curriculum. “It was project-based,” she remembers, “and that was exactly where I wanted to be in education.” She had by then acquired a teaching credential, master’s degree, husband, and two small children. Seeking farmland, they looked northward and purchased 20 logged-over acres in Mendocino County’s Anderson Valley. They lived in an old wooden trailer and, true Californians, planned a deck and hot tub for their first home improvements.

Fast-forward 14 years to 1992. Anderson Valley demographics had changed considerably. The Spanish-speaking population had swelled to 60 percent, largely because the wineries had discovered Anderson Valley and attracted many laborers from Mexico. In response, a federal grant funded a Mendocino program for English literacy. “I thought it sounded interesting,” Goodell says. “I’d never taught adults before.”

The goal of the Family English Literacy Program was to teach Mexican parents English, familiarize them with American culture, and better enable them to help their children in school. Goodell ran the program for three years until the grant ran out. Fortunately, Anderson Valley was able to open an adult school that year. Goodell took the initiative, and in 1995 the Anderson Valley Adult School came into being. Through childcare and transportation grants, Goodell managed to offer morning classes, which ran from 8:30 to 11:30. Kira Brennan was the teacher, but Goodell’s desk remained in the classroom because they only had one room.

The students, all women, were tired by mid-morning, Goodell remembers. They’d been up since 5 a.m., preparing lunches for husbands and getting kids off to school, then came to class without any food for themselves. So the teachers organized a snack schedule—two women per day bringing enchiladas, tamales, and moles, and always a salsa, but never the same one. “It was impossible not to be involved,” says Goodell. “Kira had so much pizzazz, no one could work at a desk during breaks, and the students always made sure that the maestras had food. If you didn’t eat, there was something very wrong.”

Brennan proposed a fieldtrip to the Mexican murals in San Francisco and suggested the class make a cookbook to fund the trip. It was meant to be low-budget, a Xeroxed, stapled packet. But the project grew. “We went in pretty naively,” says Brennan. “None of us realized all of the work it would entail.”

The first task was getting the recipes on paper. These were family recipes, passed down by grandmothers and great-grandmothers. When asked how many peppers, the women would motion with their hands or say, “Whatever’s in the garden.” The curriculum began focusing on teaspoons, tablespoons, and math. Finally Brennan told the women, “OK, we’ve written the recipes and translated them into English, but that doesn’t mean any old Anglo can make your salsa.” Testing was required.

For the great Salsa Cook-Off, 26 willing members of the community showed up in the autumn of 2000 to try their hands at salsa. “I’ll never forget it,” says Brennan. “We had blenders and Cuisinarts and cutting boards. The Anglos showed up at exactly 6 p.m., while the Mexican women came maybe an hour later. It was total chaos, and it was amazing.”

Ángeles Segura, one of the students and salsa contributors, attended to her recipe. “It was an incredible event, because we shared with Americans. We talked with them, even though we didn’t speak English well at that time. I was nervous to talk with the Americans, but it was a beautiful experience, I remember.” The Mexican women not only talked; they taught. It was a powerful status shift.

Adaptations to the recipes were made, the salsa-stained recipes were typed, and Brennan said, “This is too good for the copy machine! Let’s print them.” Goodell thought, “Are you kidding? On our budget?” But they got quotes, including one from a fellow in Ukiah with Mexican ancestry. They gingerly ordered 1,000 copies.

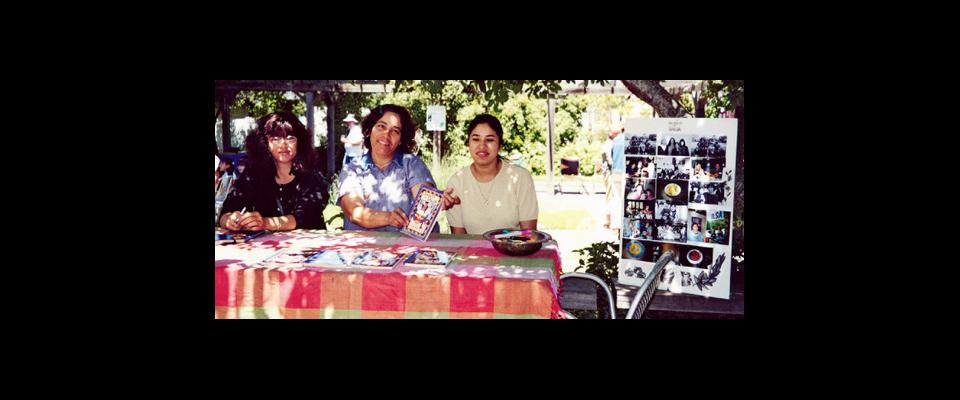

The book signing was at the Boonville Hotel; it was the first time these women had been there as guests. “There must have been 200 people,” remembers Brennan. “Everyone brought salsas and handmade tortillas, and there was a line out the door of people wanting their books signed! They were buying ten books at a time.”

They sold over half the initial printing at that event and more at local stores. Then two Berkeley alumni, Ted Bennett ’60 and Deborah Cahn, M.A. ’72, of Navarro Vineyards, decided to add the books to the gift packages they sent to their pre-release wine members, Barbara ordered 10,000 copies, and the book took off. “We saw what a wonderful project it was,” says Cahn. “It empowered these women, having something of theirs in print. It was a nice way to show the women that their traditional skills were marketable.”

Most of the revenue went to support the school, but the Adult School opened a bank account with $10,000 just for the salsa women, for yoga and mariachi classes and such, and a wee bit for a celebration. They considered a fieldtrip, but in the end decided to hold a fiesta grande and have people cook for them for a change. The resulting wild and wonderful Mexican and Anglo fiesta was a cross-cultural celebration of community such as couldn’t have been imagined a year before. The success continued, and Goodell took the women to work a variety of events that paid them for their time. “We did so many,” says Goodell. “It’s incredible, the list of conferences we spoke at and the places, like Point Reyes Farmers’ Market, where we brought salsas and books.”

Not all aspects of salsa empowerment, however, have worked as smoothly as Goodell had hoped. She wanted the women to take over the project, but encountered obstacles to her plan. Even women who seemed self-assured wouldn’t drive outside of Anderson Valley. Then there was the family issue. These women were developing new facets of their personalities, and while some husbands were supportive and proud, others were leery of their wives’ new experiences. Goodell remembers what a huge deal it was when they traveled to Point Reyes; they stayed overnight and it was the first time the women had ever been away from their families.

Goodell retired from the school in 2006 but still remains involved. “I did a lot of outreach when I was the coordinator, but we still get calls,” she says, “and there are a few women who’ll do events by themselves.” That, in Goodell’s opinion, is a major success, but she’s still waiting for one of the Salsitas to have the English skills and confidence to take over the business. “It should be in their hands” says Goodell, “But it’s important to keep the books properly and answer the phone when a store wants ten books. So I just do it in between everything else.” Everything else, for Goodell, means her homestead, with her garden, goats, sheep, geese, ducks, chickens, cats, and dog, plus the Adult School Steering Committee and the Anderson Valley Land Trust (she’s currently president) that she helped found in 1991.

Goodell believes the cookbook strengthened the community. “These women had felt they’d never be able to talk to native English speakers,” she says. “Then they found themselves doing it. It was exhilarating! Sometimes I could see them gaining confidence when they couldn’t quite see it. As a teacher, that’s what you thrive on.”

The salsa experience catapulted some of the women out of unhappy marriages and launched others into jobs. Ángeles Segura is one who thrived. “I came here from Guadalajara in 1999,” she recounts. She found it difficult to adjust to the rural isolation. “Our home had just two rooms, for us and another family, too. It rained all day, for months. I was depressed.” Then she enrolled in the Adult School. “When Barbara invited us to work, always I raised my hand. I thought, this is good experience, this is an opportunity to practice English, meet people, and maybe learn how to make a business. It changed my life.”

Segura now works full time at the school. “First I came as a student, but now I’m an assistant teacher,” she says. Since the salsa book days, she’s earned her GED and she’s active in a project called Los Hilos de la Vida (Threads of Life) that uses quilting to teach English while honoring their skills and stories. Her latest quilt was titled “Un Sueño se Hace Realidad—A Dream Come True.”

Stephanie Gold is a Northern California writer whose work has appeared in More, Psychology Today, Reader’s Digest, and other publications. Her article “Caspar’s Tale” appeared in the Winter 2009 issue of California.

For more information about The Secrets of Salsa, visit www.secretsofsalsa.com.