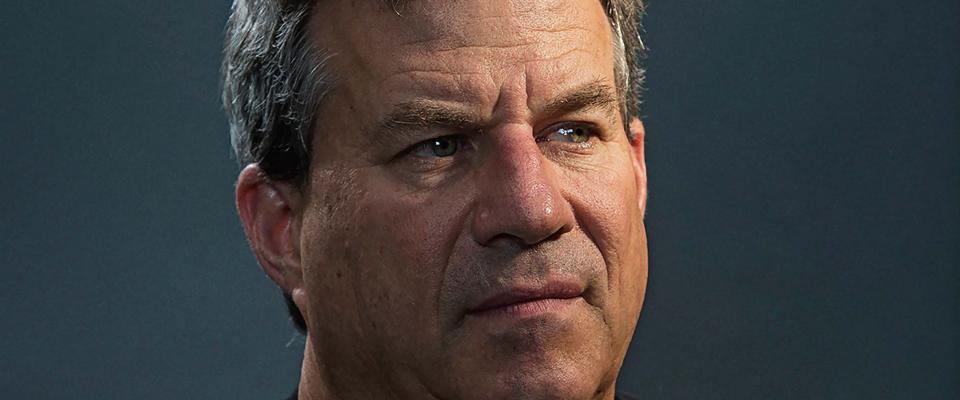

Punk rock, which was big during the years writer Sam Quinones spent at UC Berkeley, turned out to be more than just the background noise of an undergraduate life.

For Quinones, who double-majored in economics and American history, it provided an opportunity. He produced several punk shows while he was a student living at the now-shuttered Barrington Hall co-op, bringing in well-known bands such as The Dead Kennedys and Black Flag. “They were probably the biggest shows ever at Barrington Hall,” he said.

Also, punk provided him with a worldview, one that Quinones carried with him into a distinguished career in journalism.

“To me, the message of punk rock was to explode all the old hierarchies, the old customs and heroes, and tell everybody to go out there and just do it! You’ve gotta be willing to go risk it. I’ve tried to live by that ethos throughout my journalistic life.” For him, risking it meant covering crime, gangs, drugs, and the border as a daily newspaper reporter for, among other publications, the Los Angeles Times. It also meant teaching, blogging, and writing three books on Mexico, where he lived and worked for a decade.

“Mexico offered me basically as punk-rock a lifestyle as you can have,” he said. “It was an approach to life. I was out there on my own, writing my own stories, selling them on my own.”

His latest book, Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic (Bloomsbury Press, 2015), follows the intermingling paths of those who legally and illegally buy and sell opiates, both black tar heroin and prescription pain pills. (Editors’ update: in March of 2016, it won the National Book Critics Circle Award for nonfiction.

Quinones, who lives in Los Angeles, chatted over the phone with California Editor in Chief Wendy Miller about the new book.

California: Thanks in large part to popular culture—particularly television and movies—Americans have a particular image of the U.S. drug epidemic: It is a young African-American male hanging out on an urban street corner selling crack or speed. Your book upends several myths at once about the recent epidemic—who is using, who is selling, what is being sold, and where all this is taking place.

Sam Quinones: That’s what attracted me to the story in the first place. My first daily news job was in 1989 at the Stockton Record, and I’d never seen the crack epidemic up close. I was amazed to find Stockton awash in crack cocaine. And it fit a very traditional idea of how drug scourges take place. First, there’s a lot of public violence—so many drive-by shootings and car-jackings—and drugs were sold publicly. And, yeah, it was black kids selling on street corners to users of every race. And this became the collective view we have of what a drug problem looks like, one reinforced by TV shows like The Wire.

But this new epidemic was very different. For one, it was quiet—people were dying in their bedrooms while their parents tried to cover it up, telling the world that their child had died of a heart attack rather than making it public that he had died from a heroin or an OxyContin overdose. And most every one was white.

For another, there was no public violence to incite public outrage, as if the drug itself had narcotized our outrage. Because these drugs were not being sold at the point of a gun. It was not about shoot-outs for territory, not the Scarface or the Bloods and Crips model of getting market share. This was all about marketing—both the pharmaceutical companies and the Mexican heroin retailers used marketing. None of them used gunplay. As a longtime crime reporter, I thought that this was the most interesting drug story I’d ever come across.

California: Let’s back up a bit and talk a bit about the connection between the prescription pain pill epidemic and the heroin epidemic.

SQ: The key thing is that the active drug in the pills is molecularly almost identical to opiates or to heroin. It’s all based on a morphine molecule, and so they have the same effect and do the same damage to the brain, create the same euphoria and the same withdrawals.

Over a number of years, legitimate doctors, hundreds of thousands of them across the United States, prescribed pain pills for a lot of different kinds of pain. And the pills for a long time were considered virtually nonaddictive. Beginning in the mid-1990s, even today, there are lots of people who still believe that to be the case. So these pills were prescribed almost indiscriminately. And that’s eventually what created the demand for heroin.

So it’s a very different story from your classic drug scourge. It is not rooted in a mafia moving into a market. Our demand for heroin today was rooted in a change in American medicine.

California: And you point out in your book that it was a coincidence that Mexican drug dealers happened to find a U.S. market that they weren’t aware even existed.

SQ: That’s the amazing thing; there’s no conspiracy theory here. Dealers head east of the Mississippi River—primarily in Appalachia and Ohio and Indiana and Kentucky and those areas—where this massive marketing of pills has taken hold, and that’s the mid- to late ’90s. Their system takes off hugely because they stumble upon an enormous new population of addicts.

California: So if addicts switched from pills to heroin, it must be that black tar is cheaper than pills. Is that true?

SQ: In the 1970s a very large percentage of our heroin came from Asia. Heroin is a commodity, and like all commodities, various factors determine pricing. White powder is more processed and has fewer impurities than black tar, and it travels from another side of the world to the United States. So all that is going to be reflected in the price. With so much heroin coming in from Latin America nowadays—from Mexico and also Colombia—the price has collapsed. These days, the price is much cheaper than it was in the late seventies, early eighties. And it’s also more potent because it doesn’t go through so many hands, each of which would dilute it. So we are in an era of cheap heroin now, certainly the cheapest in the post–World War II era. A hit of heroin is like six bucks, so even a very serious addiction probably costs you 40, 50 bucks.

California: A day?

SQ: That’s per day, which is still a lot of money—but it’s half or less than half of what it was not long ago.

California: One of the more fascinating narrative threads running through the book is of the dealers, who look more like small-franchise business owners rather than hardened criminals.

SQ: That’s exactly right. We’re used to drug traffickers with teardrop tattoos by the eyes—career criminals. In fact, the guys selling heroin on the streets that I followed—from the Mexican town of Xalisco, Nayarit—did their best to look like the day worker in front of Home Depot. They did not flash a lot of money, they did not party—at least not until they got back to Mexico.

They made an entire system, a vast network of heroin trafficking, appear to be a bunch of small nickel-and-dime street dealers. When in fact it was this enormous web of traffickers, all of whom knew each other and came from the same small town in Mexico. They all had very consciously learned a system of how to sell and deliver heroin as if it were pizza.

It was a system they perfected before crossing the Mississippi. It was refined in areas in the west—like Portland and Reno and the San Fernando Valley—when there was no real pill addiction and the market wasn’t growing. To get business, they would steal customers from each other. But they know each other—sometimes they’re relatives. They don’t shoot each other; they offer better deals. The Xalisco Boys learn marketing and customer service. The other guy’s offering you six balloons for a hundred bucks, I’ll offer you seven. It was a bunch of come-ons and discounts, classic marketing.

California: And among the rules, you point out, is that guns are never used.

SQ: There’s no reason to use a gun. If you’re illegally in the country and you’re caught with a gun, that’s a ten-year prison sentence. They know that.

California: According to a 2014 National Institute of Drug Abuse report, more than 2 million Americans are addicted to opiate painkillers, while less than half a million are addicted to heroin. So after reading your book, it’s difficult to maintain a simplistic view of who the good guys and bad guys are in the so-called War on Drugs. Was it your intention to have readers come away from your book with a more nuanced view of pushers and users?

SQ: Yes, I hope that we can dispense with the good and the bad guys. If you want to get down to it, many of our drug problems stem from our need to have every pain problem be conveniently solved for us. Doctors are under enormous pressure to fix people, and that should not be the doctor’s job. We as American patients should be accountable for our own health. We should be making healthier life choices.

California: Something that you point out is hard to do in places where communities have disintegrated.

SQ: This book is about the state of America today and what in the last 35 years we have done to community. We have very effectively destroyed the links that might prevent people from becoming addicted to drugs, and by that I mean we have destroyed much of what binds us together.

And—this is my bigger point—what we are seeing is the end result of 35 years of exalting the free market, exalting the private sector, exalting the consumer and the individual, despising government, despising the public sector, despising the community assets that the public sector can and should provide. The end result of that is heroin—a drug that turns people into narcissistic, self-absorbed, intensely individualistic hyperconsumers. That is the point.

California: You have two dreamlands in your book—an eponymous swimming pool in Portsmouth, Ohio, and a small town in Mexico—and you talk about them as representing the waning and waxing of the American dream.

SQ: I named the book Dreamland for this pool in Portsmouth, Ohio, that was not just a place to have fun in the summer, the pool, but the place where everybody grew up under watchful eyes. Portsmouth is almost like a stand-in for the country in a lot of ways. It was a classic rust-belt town. It lost a lot of jobs, its population, its Main Street, and finally in 1993, its prize pool. Walmart became the only place to ever see people, and as the town lost its girding, drugs moved in.

Meanwhile, in Xalisco, drug money is leveling the social playing field. People who were poor, who were once disrespected in the street or in the shops, now have heroin money. They return as kings, the envy of other men. This dreamland lasts for as long as the money holds out, and then they go back and earn more, driving around cities in the U.S. with their mouths filled with little balloons of heroin.

California: The book has many threads and is richly reported and researched—no surprise considering your background. What seemed particularly distinctive, to me at least, was your compassionate treatment of everyone on both sides of the drug transaction.

SQ: The more journalism you do, the more you realize that everybody has a motive, and the motive can be really powerful and really understandable. For about a year when I was an undergrad at Berkeley, I did have this kind of crusader’s idea of what journalism should be. The muckrakers have their point. But I feel that once you take sides, your stories become more one-dimensional. To tell great stories, you cannot blink when someone you had come to believe was noble turns out to have another side to him. The side that makes him human.

From the Fall 2015 Questions of Race issue of California.